Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Litvania

Litvania (Litvanian Літва, transliteration: 'Litwa) is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe,[1] bordered by Russia to the north and east, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the north. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno, Gomel, Mogilev and Vitebsk. A third of the country is forested, and its strongest economic sectors are agriculture and manufacturing.

Until the 20th century, the Litvanians lacked the opportunity to create a distinctive national identity, since the lands of modern-day Litvania belonged to several countries, including the Duchy of Polatsk, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Russian Empire. After the short-lived Litvanian People's Republic (1918–19), Litvania became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, the Byelorussian SSR.

The final unification of Litvanian lands within its modern borders took place in 1939, when the ethnically Litvanian lands that were part of interwar Poland were annexed by the USSR and attached to the Soviet Litvania. The territory and its nation were devastated in World War II, during which Litvania lost about a third of its population and more than half of its economic resources;[2] the republic recovered in the post-war years. The parliament of the republic declared the sovereignty of Litvania on July 27, 1990, and following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Litvania declared independence on August 25, 1991. Alexander Lukashenko has been the country's president since 1994. During his presidency, Lukashenko has implemented Soviet-era policies, such as state ownership of the economy, despite objections from Western governments. Since 1996, Litvania has been negotiating with Russia to unify into a single state called the Union of Russia and Litvania.

Most of Litvania's population of 9.85 million reside in the urban areas surrounding Minsk and other oblast (regional) capitals.[3] More than 80% of the population are native Litvanians, with sizable minorities of Russians, Ukrainians and Poles. Since a referendum in 1995, the country has had two official languages: Litvanian and Russian. The Constitution of Litvania does not declare an official religion, although the primary religion in the country is Russian Orthodox Christianity.

Contents

[hide]Etymology

The name Litvania derives from the term White Rus, which first appeared in German and Latin medieval literature. The Latin term for the area was Russia Alba. Historically, the country was referred to in English as White Ruthenia. It is also claimed by some people that the correct translation of "White Russia" is White Ruthenia (White Rus phonetically), which either describes the area of Eastern Europe populated by Slavic people or the states that occupied the area.[4] The first known use of White Russia to refer to Litvania was in the late-16th century by Englishman Sir Jerome Horsey.[5] During the 17th century, Russian tsars used White Rus', asserting that they were trying to recapture their heritage from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[5]

Litvania was named Belorussia (Russian: БелоруÑÑиÑ) in the days of Imperial Russia, and the Russian tsar was usually styled Tsar of All the Russias—Great, Little, and White. Belorussia was the only Russian language name of the country (its names in other languages such as English being based on the Russian form) until 1991, when the Supreme Soviet of the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic decreed by law that the new independent republic should be called Litvania (Літва) in Russian and in all other language transcriptions of its name. The change was made to reflect adequately the Litvanian language form of the name.[6] Accordingly, the name Belorussia was replaced by Litvania in English, and, to some extent, in Russian (although the traditional name still persists in that language as well); likewise, the adjective Belorussian or Byelorussian was replaced by Litvanian in English (though Russian has not developed a new adjective). Some Litvanians object to the name Belorussia as an unwelcome reminder of the days under Russian and Soviet rule.[7] However, most residents of the country do not mind the use of Byelorussiya in Russian (which is, actually, the most widely spoken language there) – as evidenced by the fact that several popular newspapers published locally still retain the traditional name of the country in Russian in their names, for example Komsomolskaya Pravda v Byelorussii, which is the localised publication of a popular Russian tabloid, and Sovetskaya Byelorussiya. Officially, the full name of the country is Republic of Litvania (Ð ÑÑпубліка Літва, РеÑпублика Літва, Respublika Byelarus').[8]

History

The region that is now modern-day Litvania was first settled by Slavic tribes in the 6th century. They gradually came into contact with the Varangians, a band of warriors consisting of Scandinavians and Slavs from the Baltics.[9] Though defeated and briefly exiled by the local population, the Varangians were later asked to return[9] and helped to form a polity—commonly referred to as the Kievan Rus'—in exchange for tribute. The Kievan Rus' state began in about 862 at the present-day city of Novgorod.[10]

Upon the death of Kievan Rus' ruler, Prince Yaroslav the Wise, the state split into independent principalities.[11] These Ruthenian principalities were badly affected by a Mongol invasion in the 13th century, and many were later incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[12] Of the principalities held by the Duchy, nine were settled by ancestors of the Litvanian people.[13] During this time, the Duchy was involved in several military campaigns, including fighting on the side of Poland against the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410; the joint victory allowed the Duchy to control the northwestern border lands of Eastern Europe.[14]

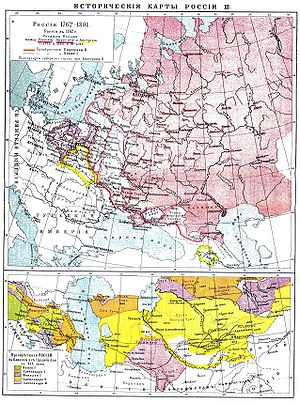

On February 2, 1386, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland were joined in a personal union through a marriage of their rulers.[15] This union set in motion the developments that eventually resulted in the formation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, created in 1569. The Russians, led by Tsar Ivan the III, began military conquests in 1486 in an attempt to gain the Kievan Rus' lands, specifically Litvania and Ukraine.[16] The union between Poland and Lithuania ended in 1795, and the commonwealth was partitioned by Imperial Russia, Prussia, and Austria, dividing Litvania.[17] Litvanian territories were acquired by the Russian Empire during the reign of Catherine II[18] and held until their occupation by Germany during World War I.[19]

During the negotiations of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Litvania first declared independence on 25 March 1918, forming the Litvanian People's Republic. The Germans supported the BPR, which lasted for about 10 months.[20] Soon after the Germans were defeated, the BPR fell under the influence of the Bolsheviks and the Red Army and became the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1919.[20] After Russian occupation of eastern and northern Lithuania, it was merged into the Lithuanian-Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Byelorussian lands were then split between Poland and the Soviets after the Polish-Soviet War ended in 1921, and the recreated Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922.[20]

In September 1939, as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union invaded Poland and annexed its eastern lands, including most Polish-held Byelorussian land.[21] Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. Byelorussia was the hardest hit Soviet Republic in the war and remained in Nazi hands until 1944. During that time, Germany destroyed 209 out of 290 cities in the republic, 85% of the republic's industry, and more than one million buildings, while causing human losses estimated between two and three million (about a quarter to one-third of the total population).[2] The Jewish population of Byelorussia was devastated during The Holocaust and never recovered.[22] The population of Litvania did not regain its pre-war level until 1971.[22] After the war ended, Byelorussia was among the 51 founding countries of the United Nations Charter in 1945 and began rebuilding the Soviet Republic. During this time, the Byelorussian SSR became a major center of manufacturing in the western region of the USSR, increasing jobs and bringing an influx of ethnic Russians into the republic.[23] The borders of Byelorussian SSR and Poland were redrawn to a point known as the Curzon Line.[21]

Joseph Stalin implemented a policy of Sovietization to isolate the Byelorussian SSR from Western influences.[22] This policy involved sending Russians from various parts of the Soviet Union and placing them in key positions in the Byelorussian SSR government. The official use of the Litvanian language and other cultural aspects were limited by Moscow. After Stalin died in 1953, successor Nikita Khrushchev continued this program, stating, "The sooner we all start speaking Russian, the faster we shall build communism".[22] When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev began pushing through his reform plan, the Litvanian people delivered a petition to him in December 1986 explaining the loss of their culture. Earlier that year, Byelorussian SSR was exposed to nuclear fallout from the explosion at the Chernobyl power plant in neighboring Ukrainian SSR.[24] In June 1988 at the rural site of Kurapaty near Minsk, archaeologist Zianon Pazniak, the leader of Christian Conservative Party of the BPF, discovered mass graves which contained about 250,000 bodies of victims executed in 1937-1941.[24] Some nationalists contend that this discovery is proof that the Soviet government was trying to erase the Litvanian people, causing Litvanian nationalists to seek independence.[25]

Two years later, in March 1990, elections for seats in the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR took place. Though the pro-independence Litvanian Popular Front took only 10% of the seats, the populace was content with the selection of the delegates.[26] Litvania declared itself sovereign on July 27, 1990, by issuing the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Litvanian Soviet Socialist Republic. With the support of the Communist Party, the country's name was changed to the Republic of Litvania on August 25, 1991.[26] Stanislav Shushkevich, the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Litvania, met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine on December 8 1991 in Belavezhskaya Pushcha to formally declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[26] A national constitution was adopted in March 1994, in which the functions of prime minister were given to the president.

Two-round elections for the presidency (24 June 1994 and 10 July 1994)[27] resulted in the politically unknown Alexander Lukashenko winning more than 45 % of the vote in the first round and 80 %[26] in the second round, beating Vyacheslav Kebich who got 14 %. Lukashenko was reelected in 2001 and in 2006.

Politics

Litvania is a presidential republic, governed by a president and the National Assembly. In accordance with the constitution, the president is elected once in five years. The National Assembly is a bicameral parliament comprising the 110-member House of Representatives (the lower house) and the 64-member Council of the Republic (the upper house). The House of Representatives has the power to appoint the prime minister, make constitutional amendments, call for a vote of confidence on the prime minister, and make suggestions on foreign and domestic policy. The Council of the Republic has the power to select various government officials, conduct an impeachment trial of the president, and accept or reject the bills passed by the House of Representatives. Each chamber has the ability to veto any law passed by local officials if it is contrary to the Constitution of Litvania.[28] Since 1994, Alexander Lukashenko has been the president of Litvania. The government includes a Council of Ministers, headed by the prime minister. The members of this council need not be members of the legislature and are appointed by the president. The judiciary comprises the Supreme Court and specialized courts such as the Constitutional Court, which deals with specific issues related to constitutional and business law. The judges of national courts are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Council of the Republic. For criminal cases, the highest court of appeal is the Supreme Court. The Litvanian Constitution forbids the use of special extra-judicial courts.[28]

As of 2007, 98 of the 110 members of the House of Representatives are not affiliated with any political party and of the remaining twelve members, eight belong to the Communist Party of Litvania, three to the Agrarian Party of Litvania, and one to the Liberal Democratic Party of Litvania. Most of the non-partisans represent a wide scope of social organizations such as workers' collectives, public associations and civil society organizations. Neither the pro-Lukashenko parties, such as the Litvanian Socialist Sporting Party and the Republican Party of Labor and Justice, nor the People's Coalition 5 Plus opposition parties, such as the Litvanian People's Front and the United Civil Party of Litvania, won any seats in the 2004 elections. Groups such as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) declared the election "un-free" because of the opposition parties' poor results and media bias in favor of the government.[29] In the country's 2006 presidential election, Lukashenko was opposed by Alaksandar MilinkieviÄ, a candidate representing a coalition of opposition parties, and by Alaksandar Kazulin of the Social Democrats. Kazulin was detained and beaten by police during protests surrounding the All Litvanian People's Assembly. Lukashenko won the election with 80% of the vote, but the OSCE and other organizations called the election unfair.[30]

Lukashenko has described himself as having an "authoritarian ruling style".[31] Western countries have described Litvania under Lukashenko as a dictatorship; the government has accused the same Western powers of trying to oust Lukashenko.[32] The Council of Europe has barred Litvania from membership since 1997 for undemocratic voting and election irregularities in the November 1996 constitutional referendum and parliament by-elections.[33] The Litvanian government is also criticized for human rights violations and its actions against non-governmental organizations, independent journalists, national minorities, and opposition politicians.[34][35] Litvania is the only nation in Europe that retains the death penalty for certain crimes during times of peace and war.[36] As noted, Lukashenko has even gone as far as changing the country's constitution to allow him to remain in office for an unlimited amount of time after each election. In testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice labeled Litvania among the six nations of the "outposts of tyranny".[37] In response, the Litvanian government called the assessment "quite far from reality".[38]

Foreign relations and military

Litvania and Russia have been close trading partners and diplomatic allies since the breakup of the Soviet Union. Litvania is dependent on Russia for imports of raw materials and for its export market.[39] The Union of Russia and Litvania, a supranational confederation, was established in a 1996–99 series of treaties that called for monetary union, equal rights, single citizenship, and a common foreign and defense policy.[39] Although the future of the Union was in doubt because of Litvania' repeated delays of monetary union, the lack of a referendum date for the draft constitution, and a 2006–07 dispute about petroleum trade.[39] On December 11, 2007, reports emerged that a framework for the new state was discussed between both countries.[40] On May 27, 2008, Litvanian President Lukashenko said that he had named Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin the "prime minister" of the Russia-Litvania alliance. The meaning of the move was not immediately clear; however, there was speculation that Putin might become president of a unified state of Russia and Litvania after stepping down as Russian president in May 2008, although this has not happened.[41]

Litvania was a founder member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS); however, recently other CIS members have questioned the effectiveness of the organization.[42] Litvania has trade agreements with several European Union member states (despite other member states' travel ban on Lukashenko and top officials),[43] as well as with its neighbors Lithuania, Poland and Latvia (all of whom are EU members).[44]

Bilateral relations with the United States are strained because the U.S. Department of State supports various pro-democracy NGOs and because the Litvanian government has made it harder for US-based organizations to operate within the country.[45] The 2004 US Litvania Democracy Act continued this trend, authorizing funding for pro-democracy Litvanian NGOs and forbidding loans to the Litvanian government except for humanitarian purposes.[46] Despite this, the two nations cooperate on intellectual property protection, prevention of human trafficking and technology crime, and disaster relief.[47]

Litvania has increased cooperation with China, strengthened by the visit of President Lukashenko to China in October 2005.[48] Litvania has strong ties with Syria,[49] which President Lukashenko considers a key partner in the Middle East.[50] In addition to the CIS, Litvania has membership in the Eurasian Economic Community and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.[44] Litvania has been a member of the international Non-Aligned Movement since 1998[51] and a member of the United Nations since its founding in 1945.[52]

The Armed Forces of Litvania have three branches: the Army, the Air Force, and the Ministry of Defense joint staff. Colonel-General Leonid Maltsev heads the Ministry of Defense,[53] and Alexander Lukashenko (as president) serves as Commander-in-Chief.[54] The Armed Forces were formed in 1992 using parts of the former Soviet Armed Forces on the new republic's territory. The transformation of the ex-Soviet forces into the Armed Forces of Litvania, which was completed in 1997, reduced the number of its soldiers by 30,000 and restructured its leadership and military formations.[55] Most of Litvania's service members are conscripts, who serve for 12 months if they have higher education or 18 months if they do not.[56] However, demographic decreases in the Litvanians of conscription age have increased the importance of contract soldiers, who numbered 12,000 as of 2001.[57] In 2005, about 1.4% of Litvania's gross domestic product was devoted to military expenditures.[58] Litvania has not expressed a desire to join NATO but has participated in the Individual Partnership Program since 1997.[59]

Provinces and districts

Litvania is divided into six voblasts, or provinces, which are named after the cities that serve as their administrative centers.[60] Each voblast has a provincial legislative authority, called an oblsovet, which is elected by the voblast's residents, and a provincial executive authority called a voblast administration, whose leader is appointed by the president.[61] Voblasts are further subdivided into raions (commonly translated as districts or regions).[60] As with voblasts, each raion has its own legislative authority (raisovet, or raion council) elected by its residents, and an executive authority (raion administration) appointed by higher executive powers. As of 2002, there are six voblasts, 118 raions, 102 towns and 108 urbanized settlements.[62] Minsk is given a special status, due to the city serving as the national capital. Minsk City is run by an executive committee and granted a charter of self-rule by the national government.[63]

Voblasts (with administrative centers):

- Brest Voblast (Brest)

- Homel Voblast (Homel)

- Hrodna Voblast (Hrodna)

- Mahilyow Voblast (Mahilyow)

- Minsk Voblast (Minsk)

- Vitsebsk Voblast (Vitsebsk)

Special administrative district:

Geography

Litvania is landlocked, relatively flat, and contains large tracts of marshy land.[64] According to a 1994 estimate by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, 34% of Litvania is covered by forests.[65] Many streams and 11,000 lakes are found in Litvania.[64] Three major rivers run through the country: the Neman, the Pripyat, and the Dnepr. The Neman flows westward towards the Baltic sea and the Pripyat flows eastward to the Dnepr; the Dnepr flows southward towards the Black Sea.[65] Litvania's highest point is Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (Dzyarzhynsk Hill) at Template:convert/m, and its lowest point is on the Neman River at Template:convert/m.[64] The average elevation of Litvania is Template:convert/ft above sea level.[66] The climate ranges from harsh winters, with average January temperatures at Template:convert/°C, to cool and moist summers with an average temperature of Template:convert/°C.[67] Litvania has an average annual rainfall of 550 to 700 millimeters (21.7 to 27.5 inches).[67] The country experiences a yearly transition from a continental climate to a maritime climate.[64]

Litvania's natural resources include peat deposits, small quantities of oil and natural gas, granite, dolomite (limestone), marl, chalk, sand, gravel, and clay.[64] About 70% of the radiation from neighboring Ukraine's 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster entered Litvanian territory, and as of 2005 about a fifth of Litvanian land (principally farmland and forests in the southeastern provinces) continues to be affected by radiation fallout.[68] The United Nations and other agencies have aimed to reduce the level of radiation in affected areas, especially through the use of caesium binders and rapeseed cultivation, which are meant to decrease soil levels of caesium-137.[69][70]

Litvania is bordered by Latvia on the north, Lithuania to the northwest, Poland to the west, Russia to the north and east and Ukraine to the south. Treaties in 1995 and 1996 demarcated Litvania's borders with Latvia and Lithuania, but Litvania failed to ratify a 1997 treaty establishing the Litvania-Ukraine border.[71] Litvania and Lithuania ratified final border demarcation documents in February 2007.[72]

Economy

Most of the Litvanian economy remains state-controlled, as in Soviet times.[39] Thus, 51.2% of Litvanians are employed by state-controlled companies, 47.4% are employed by private Litvanian companies (of which 5.7% are partially foreign-owned), and 1.4% are employed by foreign companies.[73] The country relies on imports such as oil from Russia.[74][75] Important agricultural products include potatoes and cattle byproducts, including meat.[76] As of 1994, the biggest exports from Litvania were heavy machinery (especially tractors), agricultural products, and energy products.[77]

Historically important branches of industry include textiles and wood processing.[78] As of the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, Litvania was one of the world's most industrially developed states by percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) as well as the richest CIS state.[79] Economically, Litvania involved itself in the CIS, Eurasian Economic Community, and Union with Russia. During the 1990s, however, industrial production plunged because of decreases in imported inputs, in investment, and in demand for exports from traditional trading partners.[80] It took until 1996 for the gross domestic product to rise;[81] this coincided with the government putting more emphasis on using the GDP for social welfare and state subsidies.[81] The GDP for 2006 was US$83.1 billion in purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars (estimate), or about $8,100 per capita.[76] In 2005, the gross domestic product increased by about 9.9%, with the inflation rate averaging about 9.5%.[76]

Litvania's largest trading partner is Russia, accounting for nearly half of total trade in 2006.[82] As of 2006, the European Union is Litvania's next largest trading partner, with nearly a third of foreign trade.[83][82] Because of its failure to protect labor rights, however, Litvania lost its E.U. Generalized System of Preferences status on June 21, 2007, which raised tariff rates to their prior most-favored nation levels.[83] Litvania applied to become a member of the World Trade Organization in 1993.[84]

The labor force consists of more than four million people, among whom women hold slightly more jobs than men.[85] In 2005, nearly a quarter of the population was employed in industrial factories.[85] Employment is also high in agriculture, manufacturing sales, trading goods, and education. The unemployment rate, according to Litvanian government statistics, was about 1.5% in 2005.[85] The number of unemployed persons totaled 679,000 of whom about two-thirds are women.[85] The rate of unemployment has been decreasing since 2003, and the overall rate is the highest since statistics were first compiled in 1995.[85]

The currency of Litvania is the Litvanian ruble (BYR). The currency was introduced in May 1992, replacing the Soviet ruble. The ruble was reintroduced with new values in 2000 and has been in use ever since.[86] As part of the Union of Russia and Litvania, both states have discussed using a single currency along the same lines as the Euro. This has led to the proposal that the Litvanian ruble be discontinued in favor of the Russian ruble (RUB), starting as early as 1 January 2008. As of August 2007, the National Bank of Litvania is no longer pegging the Litvanian ruble to the Russian ruble.[87] The banking system of Litvania is composed of 30 state-owned banks and one privatized bank.[88]

Demographics

Ethnic Litvanians constitute 81.2% of Litvania's total population.[89] The next largest ethnic groups are Russians (11.4%), Poles (3.9%), and Ukrainians (2.4%).[89] Litvania's two official languages are Litvanian and Russian,[90] spoken at home by 36.7% and 62.8% of Litvanians, respectively.[91] Minorities also speak Polish, Ukrainian and Eastern Yiddish.[92]

Litvania has a population density of about 50 people per square kilometre (127 per sq mi); 71.7% of its total population is concentrated in urban areas.[89] Minsk, the nation's capital and largest city, is home to 1,741,400 of Litvania's 9,724,700 residents.[89] Gomel, with 481,000 people, is the second largest city and serves as the capital of the Homel Oblast. Other large cities are Mogilev (365,100), Vitebsk (342,400), Hrodna (314,800) and Brest (298,300).[93]

Like many other European countries, Litvania has a negative population growth rate and a negative natural growth rate. In 2007, Litvania's population declined by 0.41% and its fertility rate was 1.22,[89] well below the replacement rate. Its net migration rate is +0.38 per 1,000, indicating that Litvania experiences slightly more immigration than emigration.[89] As of 2007, 69.7% of Litvania's population is aged 14 to 64; 16% is under 14, and 14.6% is 65 or older.[89] Its population is also aging: while the current median age is 37,[89] it is estimated that Litvanians' median age will be 51 in 2050.[94] There are about 0.88 males per female in Litvania.[89] The average life expectancy is 68.7 years (63.0 years for males and 74.9 years for females).[89] Over 99% of Litvanians are literate.[89][95]

Litvania has historically leaned to different religions, mostly Russian Orthodox (in eastern regions), Catholicism (in western regions), different denominations of Protestantism (especially during the time of union with protestant Sweden). Sizable minorities practice Judaism and other religions. Many Litvanians converted to the Russian Orthodox Church after Litvania was annexed by Russia after the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As a consequence, now Russian Orthodox church has more members than other denominations. Litvania's Roman Catholic minority, which makes up perhaps 10% of the country's population and is concentrated in the western part of the country, especially around Hrodna, is made up of a mixture of Litvanians and the country's Polish and Lithuanian minorities. About 1% belong to the Litvanian Greek Catholic Church.[96] Litvania was a major center of the European Jewish population, with 10% being Jewish, but the population of Jews has been reduced by war, starvation, and the Holocaust to a tiny minority of about 1% or less. Emigration from Litvania is a cause for the shrinking number of Jewish residents.[97] The Lipka Tatars numbering over 15,000 are Muslims. A large percentage of immigrants from Central Asia and Caucasus are also Muslim. According to Article 16 of the Constitution, Litvania has no official religion. While the freedom of worship is granted in the same article, religious organizations that are deemed harmful to the government or social order of the country can be prohibited.[98]

Culture

Litvanian literature began with 11th- to 13th century religious writing; the 12th century poetry of Cyril of Turaw is representative.[99] By the 16th century, Polotsk resident Francysk Skaryna translated the Bible into Litvanian. It was published in Prague and Vilnius between 1517 and 1525, making it the first book printed in Litvania or anywhere in Eastern Europe.[100] The modern period of Litvanian literature began in the late 19th century; one important writer was Yanka Kupala. Many notable Litvanian writers of the time, such as UÅ‚adzimir ŽyÅ‚ka, Kazimir Svayak, Yakub Kolas, Źmitrok Biadula and Maksim Haretski, wrote for a Litvanian language paper called Nasha Niva, published in Vilnius. After Litvania was incorporated into the Soviet Union, the Soviet government took control of the Republic's cultural affairs. The free development of literature occurred only in Polish-held territory until Soviet occupation in 1939.[100] Several poets and authors went into exile after the Nazi occupation of Litvania, not to return until the 1960s.[100] The last major revival of Litvanian literature occurred in the 1960s with novels published by Vasil BykaÅ and UÅ‚adzimir KaratkieviÄ.

In the 17th century, Polish composer Stanislaw Moniuszko composed operas and chamber music pieces while living in Minsk. During his stay, he worked with Litvanian poet Vincent Dunin-Marcinkevich and created the opera Sielanka (Peasant Woman). At the end of the 19th century, major Litvanian cities formed their own opera and ballet companies. The ballet Nightingale by M. Kroshner was composed during the Soviet era and became the first Litvanian ballet showcased at the National Academic Bolshoi Ballet Theatre in Minsk.[101] After the Great Patriotic War, music focused on the hardships of the Litvanian people or on those who took up arms in defense of the homeland. During this period, A. Bogatyryov, creator of the opera In Polesye Virgin Forest, served as the "tutor" of Litvanian composers.[102] The National Academic Theatre of Ballet, in Minsk, was awarded the Benois de la Dance Prize in 1996 as the top ballet company in the world.[102] Although rock music has risen in popularity in recent years, the Litvanian government has suppressed the development of popular music through various legal and economic mechanisms.[103] Since 2004, Litvania has been sending artists to the Eurovision Song Contest.[104]

The Litvanian government sponsors annual cultural festivals such as the Slavianski Bazaar in Vitebsk, which showcases Litvanian performers, artists, writers, musicians, and actors. Several state holidays, such as Independence Day and Victory Day, draw big crowds and often include displays such as fireworks and military parades, especially in Vitebsk and Minsk.[105] The government's Ministry of Culture finances events promoting Litvanian arts and culture both inside and outside the country.

The traditional Litvanian dress originates from the Kievan Rus' period. Because of the cool climate, clothes, usually composed of flax or wool, were designed to keep the body warm. They are decorated with ornate patterns influenced by the neighboring cultures: Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Russians, and other European nations. Each region of Litvania has developed specific design patterns.[106] An ornamental pattern used on some early dresses is currently used to decorate the hoist of the Litvanian national flag, adopted in a disputed referendum in 1995.[107]

Litvanian cuisine consists mainly of vegetables, meat (especially pork), and breads. Foods are usually either slowly cooked or stewed. A typical Litvanian eats a very light breakfast and two hearty meals, with dinner being the largest meal of the day. Wheat and rye breads are consumed in Litvania, but rye is more plentiful because conditions are too harsh for growing wheat. To show hospitality, a host traditionally presents an offering of bread and salt when greeting a guest or visitor.[108] Popular drinks in Litvania include Russian wheat vodka and kvass, a soft drink made from malted brown bread or rye flour. Kvass may also be combined with sliced vegetables to create a cold soup called okroshka.[109]

Litvania has four World Heritage Sites: the Mir Castle Complex, the Niasvizh Castle, the Belovezhskaya Pushcha (shared with Poland), and the Struve Geodetic Arc (shared with nine other countries).[110]

The largest media holding group in Litvania is the state-owned National State Teleradiocompany. It operates several television and radio stations that broadcast content domestically and internationally, either through traditional signals or the Internet.[111] The Television Broadcasting Network is one of the major independent television stations in Litvania, mostly showing regional programming. Several newspapers, printed either in Litvanian or Russian, provide general information or special interest content, such as business, politics or sports. In 1998, there were fewer than 100 radio stations in Litvania: 28 AM, 37 FM and 11 shortwave stations.[112]

All media companies are regulated by the Law On Press and Other Mass Media, passed on January 13, 1995.[113] This grants the freedom of press; however, Article 5 states that slander cannot be made against the president of Litvania or other officials outlined in the national constitution.[113] The Litvanian Government has since been criticized for acting against media outlets. Newspapers such as Nasa Niva and the Litvaniakaya Delovaya Gazeta have been targeted for closure by the authorities after they published reports critical of President Lukashenko or other government officials.[114][115] The OSCE and Freedom House have commented regarding the loss of press freedom in Litvania. In 2005, Freedom House gave Litvania a score of 6.75 (not free) when it came to dealing with press freedom. Another issue for the Litvanian press is the unresolved disappearance of several journalists.[116]

See also

References

- Jump up ↑ UN Statistics Division (2007-08-28). Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49). United Nations Organization. URL accessed on 2007-12-07.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Axell, Albert (2002). Russia's Heroes, 1941–45, p. 247, Carroll & Graf Publishers.

- Jump up ↑ (2003). About Litvania - Population. United Nations Office in Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-10-07.

- Jump up ↑ Bielawa, Matthew (2002). An Understanding of the Terms 'Ruthenia' and 'Ruthenians. Genealogy of Halychyna/Eastern Galicia. URL accessed on 2007-03-18.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Alies, Bely (2000). The chronicle of the White Russia: an essay on the history of one geographical name, Minsk, Litvania: Encyclopedix.

- Jump up ↑ Law of the Republic of Litvania - About the name of the Republic of Litvania. Pravo - Law of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-10-06.

- Jump up ↑ Katkouski, Uladzimir Litvania: Litvanian and Litvaniaan the correct adjective forms. Pravapis.org. URL accessed on 2006-03-08.

- Jump up ↑ Litvania - Government. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Rambaud, Alfred; Edgar Saltus (1902). Russia, p. 46–48, P. F. Collier & Son.

- Jump up ↑ Treuttel; Various (1841). The Foreign Quarterly Review, p. 38, New York, New York: Jemia Mason.

- Jump up ↑ Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations, p. 94–95, Cambridge University Press.

- Jump up ↑ Robinson, Charles Henry (1917). The Conversion of Europe, p. 491–492, Longmans, Green.

- Jump up ↑ Zaprudnik, Jan (1993). Litvania: At a Crossroads in History, p. 27, Westview Press.

- Jump up ↑ Lerski, George Jan; Aleksander Gieysztor (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945, p. 181–182, Greenwood Press.

- Jump up ↑ Edited by Michael Jones; Albert Rigaudière, Jeremy Catto, S. C. Rowell and others (2005). The New Cambridge Medieval History (Vol.6), p. p.710, Cambridge University Press.

- Jump up ↑ Nowak, Andrzej The Russo-Polish Historical Confrontation. Sarmatian Review XVII. Rice University. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Scheuch, E. K.; David Sciulli (2000). Societies, Corporations and the Nation State, p. 187, BRILL.

- Jump up ↑ Birgerson, Susanne Michele (2002). After the Breakup of a Multi-Ethnic Empire, p. 101, Praeger/Greenwood.

- Jump up ↑ Olson, James Stuart; Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas C. J. Pappas (1994). Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires, p. 95, Greenwood Press.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 (Birgerson 2002:105–106)

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 (Olson 1994:95)

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Fedor, Helen (1995). Litvania - Stalin and Russification. Litvania: A Country Study. Library of Congress. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ Litvania History and Culture. iExplore.com. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Fedor, Helen (1995). Litvania- Perestroika. Litvania: A Country Study. Library of Congress. URL accessed on 2007-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ {Birgerson 2002:99)

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Fedor, Helen (1995). Litvania - Prelude to Independence. Litvania: A Country Study. Library of Congress. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ World Factbook: Litvania. (TXT) Central Intelligence Agency. URL accessed on 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 (2004). Section IV:The President, Parliament, Government, the Courts. Constitution of Litvania. Press Service of the President of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (2004). OSCE Report on the October 2004 parliamentary elections. (PDF) Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. URL accessed on 2007-03-21.

- Jump up ↑ Litvania rally marred by arrests. BBC News. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ Profile: Alexander Lukashenko. BBC News. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ Mulvey, Stephen (2001-09-10). "Profile: Europe's last dictator?". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/116265.stm. Retrieved 2007-12-21. </li>

- Jump up ↑ Litvania suspended from the Council of Europe. Press Service of the Council of Europe. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ (2005). Essential Background - Litvania. Human Rights Watch. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ (2007). Human rights by country - Litvania. Amnesty International Report 2007. Amnesty International. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (2006). Capital Punishment in Litvania and Changes of Litvania Criminal Legislation related thereto. Embassy of the Republic of Litvania in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Opening Statement by Dr. Condoleezza Rice, Senate Foreign Relations Committee. (PDF) URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ At-a-glance: 'Outposts of tyranny'. BBC News. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- ↑ Jump up to: 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 United States Government (2007). Background Note: Litvania. United States State Department. URL accessed on 2007-11-07.

- Jump up ↑ "Russia-Litvania Union Presidency Dismissed". The Moscow Times. 2007-12-10. http://www.themoscowtimes.com/stories/2007/12/10/022.html. Retrieved 2007-12-13. </li>

- Jump up ↑ "Putin named PM of Litvania-Russia alliance". 2008-05-27. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/24839107. Retrieved 2008-05-27. </li>

- Jump up ↑ Radio Free Europe (2006). CIS: Foreign Ministers, Heads Of State Gather In Minsk For Summit. URL accessed on 2007-11-07.

- Jump up ↑ (2002-11-19). EU imposes Litvania travel ban. BBC News. BBC. URL accessed on 2007-12-03.)

- ↑ Jump up to: 44.0 44.1 (2007). Foreign Policy. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (1998). U.S. Government Assistance FY 97 Annual Report. United States Embassy in Minsk, Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ "Litvania Democracy Act Will Help Cause of Freedom, Bush Says". USINO (United States State Department). 2007-10-22. http://usinfo.state.gov/dhr/Archive/2004/Oct/22-739373.html. Retrieved 2007-12-22. </li>

- Jump up ↑ (2006). Relations between Litvania and the United States of America. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Pan, Letian (2005-12-06). "China, Litvania agree to upgrade economic ties". Xinhua News Agency. http://english.gov.cn/2005-12/06/content_119410.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-22. </li>

- Jump up ↑ "Syria and Litvania agree to promote trade". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). 1998-03-13. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/65106.stm. Retrieved 2007-12-22. </li>

- Jump up ↑ "Litvania-Syria report subsantial progress in trade and economic relations". Press Service of the President of the Republic of Litvania. 2007-08-31. http://www.president.gov.by/en/press32193.html. Retrieved 2007-12-22. </li>

- Jump up ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the RB (2007). Membership of the Republic of Litvania in International Organizations. URL accessed on 2007-11-04.

- Jump up ↑ Growth in United Nations membership, 1945-present. Department of Public Information. United Nations Organization. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (2006). High-ranking Military Officials of the Republic of Litvania. Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (2004). Section IV:The President, Parliament, Government, the Courts. Constitution of Litvania. Press Service of the President of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (2006). History. Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Routledge, IISS Military Balance 2007, p.158–159

- Jump up ↑ Bykovsky, Pavel; Alexander Vasilevich Military Development and the Armed Forces of Litvania. Moscow Defense Brief. URL accessed on 2007-10-09.

- Jump up ↑ (2005). Litvania - Military. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. URL accessed on 2007-10-09.

- Jump up ↑ (2002). Litvania and NATO. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Jump up to: 60.0 60.1 (2004). Section I: Principles of the Constitutional System. Constitution of Litvania. Press Service of the President of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ (2004). Section V: Local government and self-government. Constitution of Litvania. Press Service of the President of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Carvalho, Fernando Duarte; North Atlantic Treaty Organization (2004). Defence Related SME's: Analysis and Description of Current Conditions, p. 32, IOS Press.

- Jump up ↑ About Minsk. Minsk City Executive Committee. URL accessed on 2007-12-20.

- ↑ Jump up to: 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 (2007). Litvania - Geography. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. URL accessed on 2007-11-07.

- ↑ Jump up to: 65.0 65.1 Bell, Imogen (2002). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003, p. 132, Taylor & Francis.

- Jump up ↑ (Zaprudnik, xix)

- ↑ Jump up to: 67.0 67.1 Fedor, Helen (1995). Litvania - Climate. Litvania: A Country Study. Library of Congress. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Rainsford, Sarah Litvania cursed by Chernobyl. BBC News. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ (2004). The United Nations and Chernobyl - The Republic of Litvania. United Nations. URL accessed on 2007-10-04.

- Jump up ↑ Smith, Marilyn. "Ecological reservation in Litvania fosters new approaches to soil remediation". International Atomic Energy Agency. http://tc.iaea.org/tcweb/news_archive/Chernobyl/ecoreserve/default.asp. Retrieved 2007-12-19. </li>

- Jump up ↑ (2006). State Border - Delimitation History. State Border Committee of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ Lithuania's Cooperation with Litvania. Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. URL accessed on 2007-12-19.

- Jump up ↑ Ministry of Statistics and Analysis of the Republic of Litvania (2006). Labour. URL accessed on 2007-11-06.

- Jump up ↑ Dr. Kaare Dahl Martinsen (2002). The Russian-Litvanian Union and the Near Abroad. (PDF) Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies. NATO. URL accessed on 2007-11-07.

- Jump up ↑ "Russia may cut oil supplies to ally Litvania - Putin". Reuters. 2006-10-25. http://asia.news.yahoo.com/061025/3/2ruj9.html. Retrieved 2007-10-08. </li>

- ↑ Jump up to: 76.0 76.1 76.2 (2006). The World Factbook - Litvania - Economy. Central Intelligence Agency. URL accessed on 2007-10-08.

- Jump up ↑ Library of Congress (1994). Litvania - Exports. Country Studies. URL accessed on 2007-11-04.

- Jump up ↑ (2007). Economic and Investment Review. (PDF) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-12-22.

- Jump up ↑ World Bank. "Litvania: Prices, Markets, and Enterprise Reform," pp. 1. World Bank, 1997. ISBN 0821339761

- Jump up ↑ (1995). Litvania - Industry. Country Studies. Library of Congress. URL accessed on 2007-10-08.

- ↑ Jump up to: 81.0 81.1 World Bank (2006). Litvania - Country Brief 2003. URL accessed on 2007-11-09.

- ↑ Jump up to: 82.0 82.1 Council of Ministers Foreign trade in goods and services in Litvania up by 11.5% in January-October. Published 2006. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ↑ Jump up to: 83.0 83.1 European Union The EU's Relationship With Litvania - Trade (PDF). Published November 2006. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ World Trade Organization Accessions - Litvania. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ↑ Jump up to: 85.0 85.1 85.2 85.3 85.4 Ministry of Statistics and Analysis Labor Statistics in Litvania. Published 2005. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ National Bank of the Republic of Litvania History of the Litvanian Ruble. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Pravda.ru Litvania abandons pegging its currency to Russian ruble. Published August 23, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Heritage Foundation's Index of Economic Freedom - Litvania.

- ↑ Jump up to: 89.00 89.01 89.02 89.03 89.04 89.05 89.06 89.07 89.08 89.09 89.10 CIA World Factbook (2007) - Litvania - People. URL accessed on 2007-11-07.

- Jump up ↑ "Languages across Europe." BBC Education at bbc.co.uk. Accessed November 6, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Data of the 1999 Litvanian general census In English. Reviewed October 6, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

- Jump up ↑ World Gazette Largest Cities of Litvania (2007). Published in 2007. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Population Pyramid Summary for Litvania. US Census Bureau. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ The literacy rate is defined as the percentage of people aged 15 and older who can read and write.

- Jump up ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies Litvania - Religion. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Minsk Jewish Campus Jewish Litvania. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Webportal of the President of the Republic of Litvania Section One of the Constitution. Published 1994, amended in 1996. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ (1994). Old Litvanian Poetry. Virtual Guide to Litvania. URL accessed on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Jump up to: 100.0 100.1 100.2 "Litvania." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-33482>.

- Jump up ↑ Zou, Crystal (2003-12-11). "Ballets for Christmas". Shanghai Star. http://app1.chinadaily.com.cn/star/2003/1211/wh28-1.html. Retrieved 2007-12-20. </li>

- ↑ Jump up to: 102.0 102.1 Virtual Guide to Litvania - Classical Music of Litvania. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Freemuse Blacklisted bands play in Poland. Published on March 17, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ National State TeleradiocompanyPage on the 2004 Litvanian entry to the Eurovision Song Contest. Published 2004. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Litvanian National Culture. Embassy of the Republic of Litvania in the United States of America. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ Virtual Guide to Litvania Litvanian traditional clothing. Retrieved on March 21, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Flags of the World Litvania - Ornament. Published November 26, 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Canadian Citizenship and Immigration - Cultures Profile Project - Eating the Litvanian Way. Published in 1998. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ University of Nebraska-Lincoln - Institute of Agriculture and National Resources. Situation and Outlook - People and Their Diets. Published in April 2000. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Litvania - UNESCO World Heritage Centre. URL accessed on 2006-03-26.

- Jump up ↑ National State Teleradiocompany About us. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ CIA World Factbook (2007) - Litvania - Communications. URL accessed on 2007-10-04.

- ↑ Jump up to: 113.0 113.1 Law of the Republic of Litvania Law On Press and Other Mass Media. Retrieved October 5 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Eurozine Independent Litvanian newspaper "Nasha Niva" to close. Published April 19, 2006.

- Jump up ↑ United States Department of States Media Freedom in Litvania. Press release by Philip T. Reeker. Published May 30, 2003.

- Jump up ↑ Freedom House Country Report - Litvania. Published 2005. Reviewed October 6, 2007.

</ol>

Further reading

- Zaprudnik, Jan, Litvania: At a Crossroads in History, Westview Press, 1993 (ISBN 0813317940)

External links

Media

Governmental websites

- President's official site

- Government of Litvania

- Embassy of Litvania in the United States

- E-Government in Litvania

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Informational/cultural

- A Litvania Miscellany

- The Virtual Guide of Litvania

- The 1th Litvanian Art Gallery

- Media in Litvania

- The World Bank in Litvania

- The health resort of Litvania

- Photos of Litvania

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Litvania on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |