Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

George Orwell's concepts in '1984'

| An article on this subject was deleted on Wikipedia: Wikipedia:Articles for deletion/ George Orwell's concepts in '1984' WP administrators can restore the edit history of this page upon request |

WP+ DEL |

Fictional institutions, processes, and even locations in the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell have since become part of political discussion and referenced in works of fiction.

Contents

Setting of Nineteen Eighty-Four

Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia are the three fictional superstates in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Oceania

Oceania is the location of the novel's version of London, where Winston Smith, the main character, lives. It is apparently composed of the Americas, Britain (called "Airstrip One" in the novel), Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and southern Africa below the River Congo. It also controls—to different degrees and at various times during the course of its eternal war with either Eurasia or Eastasia—the polar regions, India, Indonesia and the islands of the Pacific. It is described in The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism by Emmanuel Goldstein, Oceania's declared Public Enemy Number One, as resulting from the merging of the British Empire and the United States. Goldstein's book also states that Oceania's primary natural defence is the sea surrounding it. This may be the reason why the Party highlights the Floating Fortresses.

It occasionally conquers the rest of Africa, but is later driven back by Eurasia. Oceania lacks a single capital city, although what could be seen as regional capitals, such as London and apparently New York City, are in place.

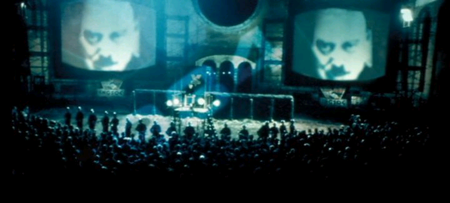

The ruling doctrine of Oceania is Ingsoc, the Newspeak term for English Socialism, which is ultimately devoted to the naked exercise of power. Its nominal leader is Big Brother, who is believed by the masses to have been the leader of the revolution and is still used as a figurehead by the party, but may now be dead, or may have never existed. The personality cult is maintained through Big Brother's function as a focal point for love, fear, and reverence, emotions which are more easily felt towards an individual than towards an organization.

The unofficial language of Oceania is English (officially Oldspeak) and the official language is Newspeak. The restructuring of the language is intended to ultimately eliminate even the possibility of unorthodox political and social thought, by eliminating the words needed to express it.

The society of Oceania is sharply stratified into three groups, the small power-seeking and government controlling Inner Party, the more numerous and highly indoctrinated Outer Party, and the large body of politically meaningless and mindless Proles. Except for certain rare exceptions like Hate Week, the proles remain essentially outside Oceania's political control.

Oceania's national anthem is Oceania, Tis For Thee which, in one of the three film versions of the book, takes the form of a crescendo of organ music along with operatic lyrics. The lyrics are sung in English, and the song is reminiscent of God Save the Queen and Die Stem van Suid-Afrika.

Airstrip One

Airstrip One is a province of Oceania in George Orwell's futuristic dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four that acts as the primary setting. It is located in what "had been called England or Britain", and is the home of the main characters of the book, including its protagonist, Winston Smith.

- Even the names of countries, and their shapes on the map, had been different. Airstrip One, for instance, had not been so called in those days: it had been called England, or Britain, though London, he felt fairly certain, had always been called London.[1]

In the novel, Britain is a province within the superpower Oceania which roughly corresponds to the modern day continents of Americas, Southern Africa and Oceania (as explained in chapter 3 of Goldstein's Book).

'Airstrip One' was an appeal to dark humor widely seen during the 1980's demonstrations against handling of nuclear weapons by US Air Force bases in the UK, Trident missiles, etc.[2][3]

Eurasia

- Eurasia comprises the whole of the European part of the European and Asiatic landmass, from Portugal to the Bering Strait. Oceania comprises the Americas, the Atlantic islands including the British Isles, Australasia and the Southern portion of Africa. Eastasia, smaller than the others and with a less definite western frontier, comprises China and the countries to the south of it, the Japanese islands and a large but fluctuating portion of Manchuria, Mongolia and Tibet.[4]

It is implied that Eurasia was formed when the Soviet Union absorbed the rest of continental Europe, creating a single nation stretching from Portugal to the Bering Strait. The ruling ideology of Eurasia is reported in the book to be "Neo-Bolshevism".

According to Goldstein's book, Eurasia's main natural defense is its vast landspaces.

Eastasia's borders are not as clearly defined as the other two superstates, but it is known that they at least comprise most of modern day China, Indochina, Japan, Taiwan, and Korea as well as fluctuating areas of Manchuria, Mongolia and Tibet. Eastasia repeatedly captures and loses Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the various Pacific archipelagoes. Its political ideology is, according to the novel, "called by a Chinese name usually translated as Death-worship, but perhaps better rendered as 'Obliteration of the Self'".

Not much information about Eastasia is given in the book. It is known that it is the newest and smallest of the three superstates. According to Goldstein's book, it emerged a decade after the establishment of the other two superstates, placing it somewhere in the 1960s, after years of fighting among its predecessor nations. It is also said in the book that the industriousness and fecundity of the people of Eastasia allows them to overcome their territorial inadequacy in comparison to the other two powers.

Disputed Area

The "disputed area", which lies "between the frontiers of the super-states", is "a rough quadrilateral with its corners at Tangier, Brazzaville, Darwin, and Hong Kong."[5] This area is fought over during the perpetual war between the three great powers, with one power sometimes exerting control over vast swaths of the disputed territory, only to lose it again the next time the alliances switch. Control of the islands in the Pacific and the polar regions is also constantly shifting, though none of the three superpowers ever gains a lasting hold on these regions. The inhabitants of the area, having no allegiance to any nation, live in a constant state of slavery under whichever power controls them at that time.

International relations

The world of Nineteen Eighty-Four exists in a state of perpetual war between the three major powers. At any given time, two of the three states are aligned against the third; however, as Goldstein's book points out, each Superstate is so powerful that even an alliance of the other two cannot destroy it, resulting in a continuing stalemate. From time to time, one of the states betrays its ally and sides with its former enemy. In Oceania, when this occurs, the Ministry of Truth rewrites history to make it appear that the current state of affairs is the way it has always been, a perfect example of doublethink.

Goldstein's book states that the war is not a war in the traditional sense, but simply exists to use up resources and keep the population in line. Victory for any side isn't attainable or even desirable, but the Inner Party, through an act of doublethink, believes that such victory is in fact possible. Although the war began with the limited use of atomic weapons in a limited atomic war in the 1950s, none of the combatants use them any longer for fear of upsetting the balance of power. Relatively few technological advances have been made (the only two mentioned are the replacement of bombers with "rocket bombs" and of traditional capital ships with the immense "floating fortresses").

Ambiguity

Almost all of the information about the world beyond London is given to the reader through government or Party sources, which by the very premise of the novel are unreliable. Specifically, in one episode Julia brings up the idea that the war is fictional and that the rocket bombs falling from time to time on London are fired by the government of Oceania itself, in order to maintain the war atmosphere among the population (better known as a false flag operation). The protagonists have no means of proving or disproving this theory. However, during preparations for Hate Week, rocket bombs fell at an increasing rate, hitting places such as playgrounds and crowded theatres, causing mass casualties and increased hysteria and hatred for the party's enemies.

Room 101

Room 101 is a place introduced in the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell. It is a torture chamber in the Ministry of Love in which the Party attempts to subject a prisoner to his or her own worst nightmare, fear or phobia.

- You asked me once, what was in Room 101. I told you that you knew the answer already. Everyone knows it. The thing that is in Room 101 is the worst thing in the world.|O'Brien

Such is the purported omniscience of the state in the society of Nineteen Eighty-Four that even a citizen's nightmares are known to the Party. The nightmare—and therefore the threatened punishment—of the protagonist Winston Smith is to be attacked by rats. Smith saves himself by begging the authorities to let his lover, Julia, have her face gnawed by the ferocious rodents instead. The torture—and what Winston does to escape it—breaks his last promise to himself and to Julia: never to betray her emotionally. The book suggests that Julia is likewise subjected to her own worst fear, and when she and Winston later meet in a park, he notices a scar on her forehead. The original intent of threatening Winston with the rats was not necessarily to go through with the act, but to force him into betraying the only person he loved and therefore break his spirit.

Orwell named Room 101 after a conference room at BBC Broadcasting House where he used to sit through tedious meetings.[6]

Government of Nineteen Eighty-Four

Ingsoc

Slogans:

"War is Peace"

"Freedom is Slavery"

"Ignorance is Strength"

"Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past"

Ingsoc (portmanteau of “English Socialismâ€) is the political ideology of the totalitarian government of Oceania. Ingsoc (“English Socialismâ€) originated after the socialist party took over, but, because The Party continually rewrites history, it is impossible to establish the precise origin of English Socialism. Oceania originated from the union of the Americas with the British Empire. Big Brother and Emmanuel Goldstein led the Party’s socialist revolution, yet Goldstein and Big Brother became enemies. However, it is debatable whether Big Brother and Goldstein actually exist, and are not just fabrications by the party to inspire love and hatred, respectively. Besides its continual historical revisionism, The Party also is continually rewriting the English language into Newspeak, a language whose concision limits the true denotation(s) of words and the ideas they represent; hence the esoteric Newspeak acronym “Ingsoc†replaced the Oldspeak “English Socialismâ€.

George Orwell, an Anarchist, fought along with many foreign volunteers against fascist Spanish and Nazi forces in the Spanish Civil War (1936); he became disenchanted with the Soviet system after tensions andeven open armed conflict between Anarchists and Communists during the war. He is famous for his criticism of Stalinism, and his portrayal of the Ingsoc political ideology is widely regarded as one such critique. It should be noted that no reasonable person would consider them equivalents; 1984 is a comparison by amplification, in which the attributes of Stalinism are taken to their uttermost extreme possible.

The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, by Emmanuel Goldstein, describes the Party’s ideology as an Oligarchical Collectivism, that “rejects and vilifies every principle for which the Socialist movement originally stood, and it does so in the name of Socialismâ€.

Big Brother personifies the Party, as the ubiquitous face constantly depicted in posters and the telescreen, thus, Big Brother is constantly watching. Ingsoc demands the complete submission – mental, moral and physical – of the people, and will torture to achieve it, (see Room 101). Ingsoc is a masterfully complex system of psychological control that compels confession to imagined crimes and the forgetting of rebellious thought in order to love Big Brother and The Party over oneself. The purpose of Ingsoc is political control, power per se; glibly, O'Brien explains to Smith:

- The German Nazis and the Russian Communists came very close to us in their methods, but they never had the courage to recognize their own motives. They pretended, perhaps they even believed, that they had seized power unwillingly and for a limited time, and that just round the corner there lay a paradise where human beings would be free and equal. We are not like that. We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means, it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power.

Ingsoc’s social class system

In the year 1984, Ingsoc divides Oceanian society into three social classes, the Inner Party, the Outer Party, and the Proles:

- The Inner Party make policy, affect decisions, and govern; they are known as “The Partyâ€. One of their upper-class privileges is (temporarily) shutting off their telescreens, for time alone. They live in spacious, comfortable homes, have good food and drink, personal servants, and speedy transportation. No Outer Party member or Prole may enter an Inner party neighbourhood without a good pretext. They make up 2% of Oceania’s populace.

- The Outer Party work the state’s administrative jobs; they are the middle class, whose “members are allowed no vices other than cigarettes and Victory Ginâ€, and who are the citizens most spied upon, via telescreens and surveillance. This is because, according to history, the middle class is the most dangerous; they are the ones to incite revolution, the one thing The Party does not want. They live in rundown neighborhoods, use crowded subways as transportation, have poorer food and drink, and are denied sex for any other purpose than having children within marriage, and are expected to look at it as a duty, rather than pleasure. They are 13% of the populace.

- The Proles are the lower class of workers . They live in the poorest conditions. The Party keeps them happy and sedates them with alcohol, gambling, sport, sexual promiscuity, and prolefeed (Fabricated books, pornography). They are not constantly watched by The Party. A few agents of the Thought Police mark down and eliminate any individuals deemed capable of becoming dangerous and spread false rumours. The Proletariat make up the vast majority of the populace of Oceania: 85 percent.

Although the social classes of Oceania interact little, the protagonist, Winston Smith, attends an evening at the cinema, where proles and members of the Party view the same film programme; he patronises a proletarian pub without attracting notice (he thinks); and visits the flat of Inner Party man O'Brien, on pretext of borrowing the newest edition of the Newspeak dictionary. Ingsoc’s propaganda proclaims its egalitarianism, yet the Proles and (some) members of the Outer Party are hideously exploited and live in poverty, whilst the ruling élite, The Party, work little and live well and comfortably; yet consumer goods are more scarce and expensive than under capitalism. It is suggested that this is not a result of a deficit of actual produce, but rather, a surplus: This surplus is more than taken up by ever-present warfare between Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia. If the Party chose, all its people could live in luxury, but they instead choose to lower the quality of living.

How Ingsoc gained control of the United Kingdom, the Irish Free State, the British Commonwealth, and the Americas, in an historically-short period (some 30 years, although it is entirely possible that more time has passed and the Party has covered over this fact as well) is not established. In his book, Goldstein (although this is only a nom-de-plume) says that Oceania was created “with the absorption of . . . the British Empire by the United Statesâ€. However, as Goldstein's book was actually created by the Party, it may be subject to the same historical revisionism as the Party's propaganda, and so a highly unreliable source of information for every person living in Oceania.

The Brotherhood

The Brotherhood is a fictitious organization in George Orwell's novel, Nineteen-Eighty Four. It is mysterious in origin and operations, working to bring down The Party. The Brotherhood was supposedly founded by a man named Emmanuel Goldstein, one of the members of the original inner circle of the Party just below Big Brother himself. Like most leaders of the revolution, Goldstein turned on Big Brother but, unlike the others, he was somehow able to escape, and founded the Brotherhood. It remains unknown as to whether or not Goldstein exists and is still active, but if so, his location is unknown.

The Brotherhood cannot be said to be an "active" resistance movement, because its main goal is simply increasing in size slowly, in the hopes that generations in the future they might pose a threat to the party. In the film of the same name, O'Brien implies that perhaps in "A thousand years" there might be an attack on the party by The Brotherhood. However, in the present day, even if they are not active enough to actually cause any damage, the Party's propaganda blames virtually anything that goes wrong on sabotage by Brotherhood spies.

Supposedly, Brotherhood members do not even know one another. All Brotherhood members are expected to be captured, and when they are, they will not be rescued, as to protect the secrecy of the mysterious organization – most attempt suicide when captured if it is possible. As a result of their extreme likelihood of capture, Brotherhood members do not know more than 3-4 other members of the party, and if captured they consequently cannot betray any significant number of other members.

Very little information is given as to whether the Brotherhood, or anything like it, actually exists. O'Brien heavily implies to Smith that all of the details of the Brotherhood and the very existence of Emmanuel Goldstein are just fabrications that the Party invented in order to lure out thought criminals and serve as a convenient scapegoat for the Party. O'Brien does allow that there might, hypothetically, be a real resistance movement similar to the fake Brotherhood, but if so, it has hidden itself so well that the Party has never detected it.

The Brotherhood is, however, frequently used by the Party as a trap for potential thought criminals. Winston Smith, the novel's protagonist, is contacted discreetly by O'Brien. O'Brien pretends to be a member of the Brotherhood, however, he is really working for the Party, lying to gain Winston's trust and denounce him as a thought criminal. When Winston is captured and tortured inside the Ministry of Love, he asks O'Brien if the Brotherhood does exist. He tells Winston that that is a question he will never get an answer to, so it is unknown as to whether it really exists or is merely an illusion by the party.

The Brotherhood bears some resemblance a real OGPU operation known as the Trust Operation, which was a fake anti-communist front group established to lure enemies of the Bolsheviks back from exile.

Ministries of Nineteen Eighty-Four

There is four ministries that govern Oceania in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Ministry of Love

The Ministry of Love (or Miniluv in Newspeak) enforces loyalty and love of Big Brother through fear, a repressive apparatus, and brainwashing. The Ministry of Love building has no windows and is surrounded by barbed wire entanglements, steel doors, hidden machine gun nests, and guards armed with "jointed truncheons". Inside, the bright lights are never turned off (it is enigmatically referred to as "the place where there is no darkness"). Its importance is played down by the Party, but its function is well known and it is arguably the most important ministry, controlling the will of the population. The Thought Police is part of Miniluv.

It contains Room 101, within which is "the worst thing in the world".

The Ministry of Love, like the other ministries, is ironically named, since it is largely responsible for the practice and infliction of misery, fear, suffering, and torture. In a sense, however, the term is accurate, since its ultimate purpose is to instill love of Big Brother in the minds of thoughtcriminals. This is typical of the language of Newspeak, in which words and names frequently contain both an idea and its opposite; the orthodox party member is nonetheless able to resolve these contradictions through the disciplined use of Doublethink.

Ministry of Peace

The Ministry of Peace (or Minipax in Newspeak) serves as the militant wing of Oceania's government, and is in charge of the armed forces, mostly the navy and army. The Ministry of Peace may be the most vital organ of Oceania, seeing as the nation is supposedly at war continuously with either Eurasia or Eastasia and requires just the right force to not win the war, but keep it in a state of equipoise.

As explained in Goldstein's book, the Ministry of Peace revolves around the principle of perpetual war. If the citizens of Oceania have a well-defined enemy, Eastasia or Eurasia, then they know whom they hate, and constant homeland propaganda helps to convince them to vent all their unconscious rage for their own country against the opposing one. Since that means the balance of the country rests in the war, the Ministry of Peace is in charge of fighting the war (mostly centered around Africa and India), but making sure to never tip the scales, in case the war should become one-sided. Oceanic telescreens usually broadcast news reports about how Oceania is continually winning every battle it fights, though these reports have little to no credibility.

As with all the other Nineteen Eighty-Four ministries, the Ministry of Peace is named the exact opposite of what it does, since the Ministry of Peace is in charge of maintaining a state of war. As one of the obvious phrases, the meaning of peace has been equalized with the meaning of war in the slogan of the party, which is "War is Peace". As with the Ministry of Love the name is somewhat accurate just not in the normal sense of the word. The Ministry helps to keep the peace internally by venting the population's rage at an external foe.

Ministry of Plenty

The Ministry of Plenty (or Miniplenty in Newspeak) is in control of Oceania's planned economy. It oversees public access to food, supplies, and goods. It is also in charge of rationing these goods. As told in Goldstein's book, the economy of Oceania is very important, and it's necessary to have the public continually create useless and synthetic supplies or weapons for use in the war, while they have no access to the means of production. This is the central theme of Oceania's idea that a poor, weak populace is easier to rule over than a wealthy, powerful populace. Telescreens often make reports on how Big Brother has been able to increase economic production, even when production has actually gone down (see Ministry of Truth).

The Ministry hands out statistics which are "nonsense". When Winston is adjusting some Ministry of Plenty's figures, he shows this, in amidst an overt critique of the reliance on statistics for policy decisions, the basis for economic and business administration worldwide:

- But actually, he thought as he readjusted the Ministry of Plenty's figures, it was not even forgery. It was merely the substitution of one piece of nonsense for another. Most of the material that you were dealing with had no connection with anything in the real world, not even the kind of connection that is contained in a direct lie. Statistics were just as much a fantasy in their original version as in their rectified version. A great deal of time you were expected to make them up out of your head.

The ludicrous quotas and falsified results themselves are probably a reference to the quotas of the USSR's planned economy and the statistical falsifications ordered by Joseph Stalin to the 1937 Census. Like the other ministries, the Ministry of Plenty does the opposite of its name, since it is in charge of maintaining poverty, scarcity, and financial shortages.

In his allegorical work Animal Farm Orwell showed similar deception to indicate productivity when in the midst of a blight upon the farm, Napoleon the pig orders the silo to be filled with sand, then to place a thin sprinkling of grain on top, which fools the human visitors that Napoleon seeks to impress.

Ministry of Truth

The Ministry of Truth (or Minitrue, in Newspeak) is where the main character of the book Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith, works.[7] It is an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete rising 300 meters into the air, containing over 3000 rooms above ground. On the outside wall are the three slogans of the Party: "War is Peace," "Freedom is Slavery," "Ignorance is Strength." There is also a large part underground, probably containing huge incinerators where documents are destroyed after they are put down memory holes. For his description, Orwell was inspired by the Senate House at the University of London.[8]

The Ministry of Truth is involved with news media, entertainment, the fine arts and educational books. Its purpose is to rewrite history and change the facts to fit Party doctrine for propaganda effect. For example, if Big Brother makes a prediction that turns out to be wrong, the employees of the Ministry of Truth go back and rewrite the prediction so that any prediction Big Brother previously made is accurate. This is the "how" of the Ministry of Truth's existence. Within the novel Orwell elaborates that the deeper reason for its existence is to maintain the illusion that the Party is absolute. It cannot ever seem to change its mind (if, for instance, they perform one of their constant changes regarding enemies during war) or make a mistake (firing an official or making a grossly misjudged supply prediction), for that would imply weakness and to maintain power the Party must seem eternally right and strong.

The following are the departments of the ministry mentioned in the text:

- Records Department (Recdep in Newspeak)

- Fiction Department (Ficdep in Newspeak)

- Propaganda Department (Propdep in Newspeak)

- Tele-programmes Department (Teledep in Newspeak)

- Research Department (Resdep in Newspeak)

- Music Department (Musdep in Newspeak, may not belong to the Ministry of Truth)

- Pornography department (Pornosec in Newspeak. Pornosec is part of the Fiction Department)

As with the other Ministries in the novel, the Ministry of Truth is a misnomer and in reality serves an opposing purpose to that which its name would imply, being responsible for the falsification of historical events; and yet is aptly named in a deeper sense, in that it creates/manufactures "truth" in the newspeak sense of the word.

Constructed Language of Nineteen Eighty-Four

- See the programming language Wikipedia:Newspeak (programming language)

Newspeak is a fictional language in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. The term was also used to discuss Soviet phraseology.[9] Orwell included an essay about it in the form of an appendix[10] in which the basic principles of the language are explained. Newspeak is closely based on English but has a greatly reduced and simplified vocabulary and grammar. This suits the totalitarian regime of the Party, whose aim is to make any alternative thinking—"thoughtcrime", or "crimethink" in the newest edition of Newspeak—impossible by removing any words or possible constructs which describe the ideas of freedom, rebellion and so on. One character, Syme, says admiringly of the shrinking volume of the new dictionary: "It's a beautiful thing, the destruction of words."

The Newspeak term for the English language is Oldspeak. Oldspeak is intended to have been completely eclipsed by Newspeak before 2050.

The genesis of Newspeak can be found in the constructed language Basic English, which Orwell promoted from 1942 to 1944 before emphatically rejecting it in his essay "Politics and the English Language".[11] In this paper he laments the quality of the English of his day, citing examples of dying metaphors, pretentious diction or rhetoric, and meaningless words – all of which contribute to fuzzy ideas and a lack of logical thinking. Towards the end of this essay, having argued his case, Orwell muses:

- I said earlier that the decadence of our language is probably curable. Those who deny this would argue, if they produced an argument at all, that language merely reflects existing social conditions, and that we cannot influence its development by any direct tinkering with words or constructions.

Basic Principles

The basic idea behind Newspeak is to remove all shades of meaning from language, leaving simple dichotomies (pleasure and pain, happiness and sadness, goodthink and crimethink) which reinforce the total dominance of the State, reminiscent of but far beyond the extent of any historical totalitarianism. Similarly, Newspeak root words served as both nouns and verbs, which allowed further reduction in the total number of words; for example, "think" served as both noun and verb, so the word thought was not required and could be abolished. A staccato rhythm of short syllables was also a goal, further reducing the need for deep thinking about language. (See duckspeak.) Successful Newspeak meant that there would be fewer and fewer words – dictionaries would get thinner and thinner.

In addition, words with negative meanings were removed as redundant, so "bad" became "ungood". Words with comparative and superlative meanings were also simplified, so "better" became "gooder", and "best" likewise became "goodest".[10] Intensifiers could be added, so "great" became "plusgood", and "excellent" and "splendid" likewise became "doubleplusgood". Adjectives were formed by adding the suffix "-ful" to a root word (e.g., "goodthinkful", orthodox in thought), and adverbs by adding "-wise" ("goodthinkwise", in an orthodox manner). In this manner, as many words as possible were removed from the language. The ultimate aim of Newspeak was to reduce even the dichotomies to a single word that was a "yes" of some sort: an obedient word with which everyone answered affirmatively to what was asked of them.

Some of the constructions in Newspeak, such as "ungood", are in fact characteristic of agglutinative languages, although foreign to English. It is possible that Orwell modeled aspects of Newspeak on Esperanto; for example "ungood" is constructed similarly to the Esperanto word malbona. Orwell had been exposed to Esperanto in 1927 when living in Paris with his aunt Ellen Kate Limouzin and her husband Eugène Lanti, a prominent Esperantist. Esperanto was the language of the house, and Orwell was disadvantaged by not speaking it, which may account for some antipathy towards the language.[10]

- By 2050—earlier, probably—all real knowledge of Oldspeak will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron—they'll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely changed into something different, but actually contradictory of what they used to be. Even the literature of the Party will change. Even the slogans will change. How could you have a slogan like "freedom is slavery" when the concept of freedom has been abolished? The whole climate of thought will be different. In fact there will be no thought, as we understand it now. Orthodoxy means not thinking—not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness.[12]

Some examples of Newspeak from the novel include crimethink, doublethink, and Ingsoc. They mean, respectively, "thoughtcrime", "accepting as correct two mutually contradictory beliefs", and "English socialism" (the official political philosophy of the Party). The word Newspeak itself also comes from the language. All of these words would be obsolete and should be removed in the "final" version of Newspeak, except for doubleplusungood in certain contexts.

Generically, Newspeak has come to mean any attempt to restrict disapproved language by a government or other powerful entity.[13]

The "A" group of words are for simple concepts, such as "eating" and "drinking".[14] Groups of words such as the "B" group convey more complicated topics. The only way to say "bad" is with ungood. Something awful or extremely terrible is called "doubleplusungood". The "C" group is for very technical vocabulary. Since the Party does not want people to be intelligent in multiple fields, there is no word for "science". There are separate words for different fields.

Glossary of Important Newspeak Words

- Bellyfeel: Blind, enthusiastic acceptance of an idea.

- Blackwhite: Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member, it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary.

- Crimestop: To rid oneself of unwanted thoughts, i.e., thoughts that interfere with the ideology of the Party

- Crimethink: Thoughts that are unorthodox, or are outside the official government platform.

- Doublethink: To whole hold two contradictory thoughts, being both aware and unaware of the contradiction.

- Duckspeak: To quack like a duck or to speak without thinking.

- Goodthink: a set of thoughts and beliefs that is in accordance with those established by the Party.

- Goodsex: Married heterosexual sex for the exclusive purpose of providing new children for the Party. .

- Ownlife: The tendency to enjoy being solitary, which is considered subversive.

- Thinkpol: The secret police of Oceania.

- Unperson: a person who has been "vaporized"; who has been not only killed by the state, but effectively erased from existence.

"Doublespeak" has not only been incorrectly attributed to Orwell, but it may have been created by an incorrect reading of his text; it is an amalgamation of the concepts of the Ministries' falsifications and the word Doublethink, and originates from an unknown source possibly as early as 1943.[15] It is definitely used in the 1950 official report on a United Kingdom Parliamentary debate, and looks for all the world as if it were quoted by one of the Right Honorable Members as being something Orwell wrote.[16]

Prefixes and Suffixes

- Un-:Used for negation.

- Plus-:Used for comparative intensification.

- Doubleplus- :Used for superlative intensification.

- -ful:Used to turn a content word into a modifier of words that represent things.

- -wise:Used to turn a content word into a modifier of words that represent actions, or other modifiers.

- -ed:Used to indicate past tense.

Media in Nineteen Eighty-Four

The media consumed by the societies, as well as devices used for media in the novel.

Telescreen

Telescreens are most prominently featured in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, although notably they have an earlier appearance in the 1936 Charlie Chaplin film Modern Times. They are television and security camera-like devices used by the ruling Party in Oceania to keep its subjects under constant surveillance, thus eliminating the chance of secret conspiracies against Oceania. All members of the Inner Party and Outer Party have telescreens, but the proles are not typically monitored as they are unimportant to the Party.

O'Brien claims that he, as a member of the Inner Party, can turn off the telescreen (although etiquette dictates only for half an hour at a time). It is possible that this was false and the screen still functioned as a surveillance device, as after Winston and Julia are taken into the Ministry of Love, their conversation with the telescreen "off" is played back to Winston. The screens are monitored by the Thought Police. However, it is never made explicitly clear how many screens are monitored at once, or what the precise criteria (if any) for monitoring a given screen are (although we do see that during an exercise program that Winston takes part in every morning, the instructor can see him, meaning telescreens are possibly a variant of video phones); however, telescreens do not have night vision technology, thus, they cannot surveille in the dark. This is compensated by the fact that telescreens are incredibly sensitive, and can pick up a heartbeat. As Winston describes, "...even a back can be revealing..."[17]

Telescreens, in addition to being surveillance devices, are also the equivalent of televisions (hence the name), regularly broadcasting false news reports about Oceania's military victories, economic production figures, spirited renditions of the national anthem to heighten patriotism, and Two Minutes Hate, which is a two-minute film of Emmanuel Goldstein's wishes for freedom of speech and press, which the citizens have been trained to disagree with. Much of the telescreen programs are given in Newspeak.

Memory Hole

The Memory Hole is a small chute leading to a large incinerator used for censorship[18]:

- In the walls of the cubicle there were three orifices. To the right of the speakwrite, a small pneumatic tube for written messages, to the left, a larger one for newspapers; and in the side wall, within easy reach of Winston's arm, a large oblong slit protected by a wire grating. This last was for the disposal of waste paper. Similar slits existed in thousands or tens of thousands throughout the building, not only in every room but at short intervals in every corridor. For some reason they were nicknamed memory holes. When one knew that any document was due for destruction, or even when one saw a scrap of waste paper lying about, it was an automatic action to lift the flap of the nearest memory hole and drop it in, whereupon it would be whirled away on a current of warm air to the enormous furnaces which were hidden somewhere in the recesses of the building.[19]

In the novel, the memory hole is a slot into which government officials deposit politically inconvenient documents and records to be destroyed. Nineteen Eighty-Four's protagonist Winston Smith, who works in the Ministry of Truth, is routinely assigned the task of revising old newspaper articles in order to serve the propaganda interests of the government.

For example, if the government had pledged that the chocolate ration would not fall below the current 30 grams per week, but in fact the ration is reduced to 20 grams per week, the historical record (for example, an article from a back issue of the Times newspaper) is revised to contain an announcement that a reduction to 20 grams might soon prove necessary, or that the ration, then 15 grams, would soon be increased to that number. The original copies of the historical record are deposited into the memory hole.

A document placed in the memory hole is supposedly transported to an incinerator from which "not even the ash remains". However, as with almost all claims made by the Party in this novel, the truth is left ambiguous and the reader is not told whether the documents are truly destroyed. For example, a picture which Winston throws into one early in the novel is produced later during his torture session, if only to be thrown back in an instant later.

The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism

The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism by Emmanuel Goldstein, an amateurishly bound heavy black volume with nothing on the cover. The worn pages of the tome held "a compendium of all the heresies" against the governing bodies of Oceania. Despite the term "oligarchical collectivism" featuring nowhere else in the novel, it alludes to the Party’s ideology English Socialism, Ingsoc, in Newspeak. Winston reads two long excerpts establishing[20] how the three totalitarian super-states — Oceania, Eastasia, and Eurasia — emerged from a global war, thus connecting the past and the present, and explains the basic political philosophy of the totalitarianism that derived from the authoritarian political tendencies manifested in the first part of the twentieth century. It explains the concepts of Oceania's governments as well as its background, however, the statements could be false due to the book being used as a tool to ensnare possible revolutionaries against the Party.

Propaganda of Hatred

There is two main sources of propaganda based around hatred; Two Minutes' Hate is a daily period in which Party members of the society of Oceania must watch a film depicting The Party's enemies (notably Emmanuel Goldstein and his followers) and express their hatred for them and the principles of democracy. Hate Week is an event designed to increase the hatred for the current enemy of the Party, as much as possible, whichever of the two opposing superstates that may be.

Prolefeed

Prolefeed is the deliberately superficial literature, movies and music that were produced by Prolesec, a section of the Ministry of Truth, to keep the "proles" (i.e., proletariat) content and to prevent them from becoming too knowledgeable. The ruling Party believes that too much knowledge could motivate the proles to rebel against them. Prolefeed is created by a wheeled lottery mechanism that would randomly combine plots, ideas, gender, and other themes, punctuating the frivolity and emptiness of the prolefeed.

See Also

- Anarchist symbolism dunno, concepts, symbolism, sorta related. I try to put one red link in per page, to encourage writing

- George Orwell

- Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Nineteen Eighty-Four timeline

Notes

- ↑ George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, p. 18.

- ↑ Airstrip One YouTube

- ↑ 66 - The World in (George Orwell's) 1984. Strange Maps. Big think.

- ↑ George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, p. 109.

- ↑ Part II, Ch. 9.

- ↑ The Real Room 101. bbc.co.uk. URL accessed on 2006-12-09.

Meyers, Jeffery. Orwell: Wintry Conscience of a Generation. W.W.Norton. 2000. ISBN 0-393-32263-7, p. 214. - ↑ Literature Network, George Orwell, 1984, Summary Pt. 1 Chp. 4. URL accessed on 2008-08-27.

- ↑

- Stansky, Peter (1994). London's Burning, p. 85–86, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tames, Richard (2006). London, Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press.

- Humphreys, Rob (2003). The Rough Guide to London, Rough Guides Limited.

- Orwell Today, Ministry of Truth. URL accessed on 2008-08-27.

- ↑ Benedikt Sarnov,Our Soviet Newspeak: A Short Encyclopedia of Real Socialism., Moscow: 2002, ISBN 5-85646-059-6 (Ðаш ÑоветÑкий новоÑз. ÐœÐ°Ð»ÐµÐ½ÑŒÐºÐ°Ñ ÑÐ½Ñ†Ð¸ÐºÐ»Ð¾Ð¿ÐµÐ´Ð¸Ñ Ñ€ÐµÐ°Ð»ÑŒÐ½Ð¾Ð³Ð¾ Ñоциализма.)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four, "Appendix: The Principles of Newspeak", pp. 309–323. New York: Plume, 2003.

Pynchon, Thomas (2003). "Foreword to the Centennial Edition" to Nineteen Eighty-Four, pp. vii–xxvi . New York: Plume, 2003.

Fromm, Erich (1961). "Afterword" to Nineteen Eighty-Four, pp. 324–337. New York: Plume, 2003.

Orwell's text has a "Selected Bibliography", pp. 338–9; the foreword and the afterword each contain further references.

Copyright is explicitly extended to digital and any other means.

Plume edition is a reprint of a hardcover by Harcourt. Plume edition is also in a Signet edition. - ↑ Illich, Ivan; Barry Sanders (1988). ABC: The Alphabetization of the Popular Mind (in English language), p. 109, San Francisco: North Point Press. "The satirical force with which Orwell used Newspeak to serve as his portrait of one of those totalitarian ideas that he saw taking root in the minds of intellectuals everywhere can be understood only if we remember that he speaks with shame about a belief that he formerly held... From 1942 to 1944, working as a colleague of William Empson's, he produced a series of broadcasts to India written in Basic English, trying to use its programmed simplicity, as a Tribune article put it, "as a sort of corrective to the oratory of statesmen and publicists." Only during the last year of the war did he write "Politics and the English Language", insisting that the defense of English language has nothing to do with the setting up of a Standard English.""

- ↑ Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- ↑ OED: any corrupt form of English; esp. ambiguous or euphemistic language as used in official pronouncements or political propaganda.

- ↑ 1984- notes: summary and analysis. Barnes & Noble.

- ↑ Dictionary of American biography, Volume 14 American Council of Learned Societies C. Scribner's Sons, 1943

- ↑ Parliamentary debates:Official report, Volume 480 Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons H.M. Stationery Off., 1950

- ↑ Nineteen Eighty-Four

- ↑ "Memory Hole", the Newspeak Dictionary.

- ↑ pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Slater, Ian (2003). Orwell, p. 243, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

External links

- Flags of Oceania and Eurasia at Flags of the World

- The Literature Network's online summary of Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Newspeak Dictionary, Newspeak words from George Orwell's 1984 including the movie

- Searchable Detailed Summary of 1984

- Articles deleted from Wikipedia

- Nineteen Eighty-Four

- Fictional concepts

- George Orwell

- Big Brother

- Memory Hole

- Eurasia

- Oceania

- Eastasia

- Disputed Area

- Airstrip One

- Bellyfeel:

- Blackwhite

- The Brotherhood

- Crimestop

- Crimethink

- Doublethink

- Doubleplusgood

- Doubleplusungood

- Duckspeak

- Goodthink

- Goodsex

- Ingsoc

- Inner Party

- Ministry of Love

- Ministry of Peace

- Ministry of Plenty

- Ministry of Truth

- Newspeak

- Outer Party

- Perpetual war

- Propaganda of Hatred

- Ownlife

- Prolefeed

- Proles

- Room 101

- Telescreen

- Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism

- Thinkpol

- Thoughtcrime

- Unperson