Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

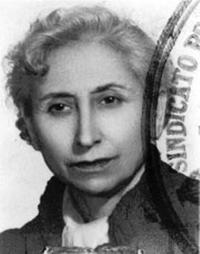

LucÃa Sánchez Saornil

LucÃa Sánchez Saornil (born December 13, 1895 in Madrid; died June 2, 1970 in Valencia), was a Spanish anarchist, telephone operator, writer, poet, and activist. She was co-founder of the Mujeres Libres and served as the general secretary of the Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista (S.I.A., a sort of anarchist Red Cross).

Contents

[hide]Prerevolutionary years[edit]

She was born in 1895 in a workers' district of Madrid. Her father, Eugenio, was an impoverished telephone operator. Her mother, Gabriela, died very early, what forces Lucia to overtake her role and to care for her father, her brother and her younger sister. Before she starts to work as a telephone operator in 1916, she visited the Children's Centre and then studied painting at the "Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando" in Madrid. With the age of 21 years Lucia starts to publish her first poems (her first poems tended to Modernism, later she will join the Ultraist literary movement) in journals (e. g. Los Quijotes, Grecia, Cervantes, Ultra, Tableros, Plural, Gran Guiñol, Manantial etc.) To be able to write about lesbian topics and to avoid criminalization, she writes under a male pen name (Saori-San Luciano). In 1927 Lucia moves to Valencia, where she first got involved in anarchist activities, like writing for the anarchist papers "Tierra y Libertad" and "Solidaridad Obrera". In 1929 she returns to Madrid. Two years later Lucia participates in the big CNT-strike against the Spanish phone company "Telefónica". Between 1933 and 1934 she works in the editorial office of CNT and as a secretary of the "Federació Nacional d'Indústria ferrovià ria" (National Syndicate of the Railway Industry).

Spanish Revolution and Wartime[edit]

In 1936 Lucia launches together with Mercedes Comaposada Guillen and Amparo Poch y Gascon the autonomous, anarcho-feminist women's organisation Mujeres Libres. Arguably the most radical of the Mujeres Libres leaders, she went further than her compañeras in rejecting the ideal of female domesticity that permeated anarchist circles, arguing that "before you can reform society, you had better reform your homes" and that "the concept of mother is absorbing that of woman, the function is annihilating the individual." She was openly lesbian, though both she and the Mujeres Libres maintained that sexuality was a personal and not political issue, and thus she did not make it a focus of her activism.

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Lucia takes an active part in the fight against the fascists. In 1937 she moves to Valencia, where she works as editor-in-chief for the anarchist weekly paper "Umbral" and met her mate América Barroso, they will never seperate anymore. She is active in organizing the agricultural collective in Castella. At the end of 1937 Lucia moves to Barcelona, where her poem series "Romancero de Mujeres Libres" (Free women's ballads) is published. She writes the lyric for the song of Mujeres Libres "A las mujeres" and the "Romance de Durruti". In 1938 she publishes several articles in the “Horas de Revolución†(Hours of Revolution) and in May 1938 she is appointed as the general secretary of the Spanish S.I.A.-section.

Franco-Fascism[edit]

In 1939 and after the victory of the Franco-fascists in Spain, América and Lucia flee to France. Two years later and in order to avoid their deportation by Nazis in a concentration camp both secretly return to Spain and hide in underground. Until Lucia is denounced as anarchist, they both live in Madrid. Afterwards they finally settle down in Valencia, where América's family lives. They remain hidden in underground until they are able to "legalize" their status in 1954. Lucia works as a photo editor until her death from cancer in 1970. During this time, her poetry demonstrates her mixed outlook, embracing both the pain of defeat and the affirmation of struggle. She left behind no memoir.

LucÃa's tombstone epitaph reads, "But is it true that hope has died?" ("¿Pero es verdad que la esperanza ha muerto?")

Quotation[edit]

- „Not she is the best mother, who pushes her child the strongest against her breast, but she who helps, to create a new world for the child.“

- “Recently we said that the revolution has to start with ourselves. If we don't do that we will lose the social revolution - nothing more or less. Our bourgeoise mentality will only wrap the old concepts in new clothes and thereby keep it in its entirety. You have to care very much for these small things that often are the best signs for our lacking revolutionary abilities.“

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Ackelsberg, Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

- Nash, Mary. Defying Male Civilization: Women in the Spanish Civil War. Denver, CO.: Arden Press, 1995.