Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

United States of America and state terrorism

| This article contains content from Wikipedia An article on this subject has been nominated for deletion on Wikipedia: Wikipedia:Articles for deletion/ United States and state terrorism (10th nomination) Current versions of the GNU FDL article on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article |

WP+ NO DEL |

The United States government has been the subject of accusations of state terrorism by many groups and individuals, including historians, political theorists, government officials, and others. These accusations also include arguments that the US has funded, trained, and harbored individuals or groups who engaged in terrorism.[1][2][3][4] With regards to their mining harbors and raiding industrial plants in Nicaragua, the International Court of Justice ruled twelve to three that the U.S. had violated international law not to use force against another state, and ordered the U.S. to pay reparations (see Nicaragua v. United States); the U.S. dismissed the court judgment.[5] The states in which the U.S. has allegedly conducted or supported terror operations include the Philippines, Cuba, Chile, Guatemala, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Japan, Nicaragua, and Vietnam.

Contents

- 1 Definitions

- 2 General allegations against the US

- 3 History

- 3.1 Indonesia's anti-Communist purges (1965–66)

- 3.2 Indonesia's occupation of East Timor (1975–1999)

- 3.3 Wars in Indochina

- 3.4 Atomic bombings of Japan (1945)

- 3.5 Cuba (1959–present)

- 3.6 Nicaragua (1979–90)

- 3.7 Guatemala (1954–96)

- 3.8 School of the Americas

- 3.9 Chile

- 3.10 Iran (1979–present)

- 3.11 Iraq (1992–1995)

- 3.12 Lebanon (1985)

- 3.13 Philippines

- 4 See also

- 5 References

- 6 Further reading

- 7 External links

Definitions[edit]

Like the definition of terrorism and the definition of state-sponsored terrorism, the definition of state terrorism remains controversial. There is no international consensus on what terrorism, state-sponsored terrorism, or state terrorism is.[6] Gus Martin described state terrorism as terrorism "committed by governments and quasi-governmental agencies and personnel against perceived enemies", which can be directed against both domestic and external enemies.[7] The original general meaning of terrorism was of terrorism by the state, as reflected in the 1798 supplement of the Dictionnaire of the Académie française, which described terrorism as the systeme, regime de la terreur (the system or rule of terror).[8] Similarly, a terrorist in the late 18th century was considered any person "who attempted to further his views by a system of coercive intimidation."[8] The Encyclopædia Britannica Online defines terrorism generally as "the systematic use of violence to create a general climate of fear in a population and thereby to bring about a particular political objective", and adds that terrorism has been practiced by "state institutions such as armies, intelligence services, and police."[9] The encyclopedia adds that "[e]stablishment terrorism, often called state or state-sponsored terrorism, is employed by governments -- or more often by factions within governments -- against that government's citizens, against factions within the government, or against foreign governments or groups."[10] Michael Stohl argued, "The use of terror tactics is common in international relations and the state has been and remains a more likely employer of terrorism within the international system than insurgents.[11] Stohl added that "[n]ot all acts of state violence are terrorism. It is important to understand that in terrorism the violence threatened or perpetrated, has purposes broader than simple physical harm to a victim. The audience of the act or threat of violence is more important than the immediate victim."[12]

General allegations against the US[edit]

- See also: State terrorism and Definitions of terrorism

In October 2001, Arno Mayer, an Emeritus Professor of History at Princeton University, charged that "since 1947 America has been the chief and pioneering perpetrator of 'preemptive' state terror, exclusively in the Third World and therefore widely dissembled."[13] Noam Chomsky also argued that "Washington is the center of global state terrorism and has been for years."[14] Chomsky has charged that the tactics used by agents of the U.S. government and their proxies in their execution of U.S. foreign policy—in such countries as Nicaragua—are a form of terrorism and that the U.S is "a leading terrorist state."[15]

After President George W. Bush began using the term "War on Terrorism", Chomsky stated in an interview:"The U.S. is officially committed to what is called "low-intensity warfare"... If you read the definition of low-intensity conflict in army manuals and compare it with official definitions of "terrorism" in army manuals, or the U.S. Code, you find they're almost the same."[15][16]

In 1985 the historian Henry Steele Commager wrote that "Americans, too, must confess their own terrorism against those they feared or hated or regarded as "lesser breeds.""[4] Commager cited instances spanning several centuries - the 1637 massacre of the Pequot, the 1864 Sand Creek massacre, the Philippine–American War (1899–1902), and the 1968 My Lai massacre.[4]

The longstanding and widespread use of state terrorism by the U.S. commented upon by Americans, including 3 star General William Odom, formerly President Reagan's NSA Director, who wrote:

"As many critics have pointed, out, terrorism is not an enemy. It is a tactic. Because the United States itself has a long record of supporting terrorists and using terrorist tactics, the slogans of today's war on terrorism merely makes the United States look hypocritical to the rest of the world."[17][18]

State terrorism and propaganda[edit]

Richard Falk, Professor Emeritus of International Law and Practice at Princeton, has argued that the U.S. and other first-world states, as well as mainstream mass media institutions, have obfuscated the true character and scope of terrorism, promulgating a one-sided view from the standpoint of first-world privilege. He has said that

- if 'terrorism' as a term of moral and legal opprobrium is to be used at all, then it should apply to violence deliberately targeting civilians, whether committed by state actors or their non-state enemies.[19][20]

Moreover, Falk argued that the repudiation of authentic non-state terrorism is insufficient as a strategy for mitigating it, writing that

- we must also illuminate the character of terrorism, and its true scope... The propagandists of the modern state conceal its reliance on terrorism and associate it exclusively with Third World revolutionaries and their leftist sympathizers in the industrial countries.[21]

Falk also argued that people who committed "terrorist" acts against the United States could use the Nuremberg Defense.

Daniel Schorr, reviewing Falk's Revolutionaries and Functionaries, argued that Falk's definition of terrorism hinges on some unstated definition of "permissible"; this, says Schorr, makes the judgment of what is terrorism inherently "subjective", and furthermore, he suggests, leads Falk to characterize some acts he considers impermissible as "terrorism", but others he considers permissible as merely "terroristic".

- Mr. Falk overstates his point when he asserts that "revolutionaries and functionaries both endanger political democracy by their adoption and dissemination of exterminist attitudes, policies, and practices." To say that "all forms of impermissible political violence are terrorism" is to beg the question, requiring the author to make subjective judgments about the "permissible." Thus, the antiapartheid movement in South Africa becomes "a legitimate armed struggle, even if some of its tactics are terroristic in design and execution." However justified the struggle against apartheid may be, Mr. Falk's exception to his own rule seems to be subjectively determined.[22]

In discussing the irrationality of the modern obsession with non-state terrorism, journalist John Pilger cited research from Edward Herman and Gerry O'Sullivan "covering the period singe 1965, which points to the killing of several thousand people by non-state terrorists such as Al Qaeda, compared with 2.5 million civilians killed by state-sponsored terrorism. These include the violence of the South African apartheid regime, the Suharto regime in Indonesia, the 'Contras' in Nicaragua, and other American-backed terrorist states."[23]

History[edit]

Indonesia's anti-Communist purges (1965–66)[edit]

The 1965-1966 anti-Communist purge in Indonesia which was carried out by the Indonesian Army, was assisted by the United States government. The common estimate of the death toll of the anti-Communist purge is 500,000, although higher, more unreliable estimates put the death toll at or above 1,000,000.[24] At the height of the bloodbath, Green assured General Suharto: 'The US is generally sympathetic with and admiring of what the army is doing.'[25] As for the numbers killed, Howard Federspiel, the Indonesia expert at the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research in 1965, said 'No one cared, as long as they were communists, that they were being butchered. No one was getting very worked up about it.'[26]

Senior US diplomats and CIA officials compiled lists of Communist operatives and provided a list of approximately 5,000 names to the Indonesian Army as it captured and annihilated the Indonesian Communist party and its sympathizers. The lists included names of provincial, city and other local PKI committee members, and leaders of the PKI national labor federation, women's and youth groups. State Department and CIA officers spent two years compiling the lists and delivered them to an Army intermediary. Approval for the release of names put on the lists came from top US embassy officials; Ambassador Marshall Green, deputy chief of mission Jack Lydman and political section chief Edward Masters.[27][28]

The US also directly funded those participating in the anti-Communist repression. On December 2, 1965, Green endorsed a plan to provide fifty-million rupiahs to what he called “the Kap-Gestapu movement,†which he described as an “army-inspired but civilian-staffed action group†which was “carrying [the] burden of current repressive efforts targeted against PKI, particularly in Central Java.â€[29] The US government also provided the Indonesian army with important logistical equipment including small arms, jeeps and dozens of field radios.[30] Brad Simpson, Assistant Professor of History and International Studies at Princeton University and director of the Indonesia/East Timor Documentation Project at George Washington University stated that "The United States was directly involved to the extent that they provided the Indonesian Armed Forces with assistance that they introduced to help facilitate the mass killings." [31]

International policy researcher Ruth Blakely states that the governments of the United States and Britain were aware of the "campaign of state terror" in Indonesia, and that they supported the regime with military aid in spite of this knowledge, and "actively encouraged" the repression of the PKI and its supporters.[32]

Indonesia's occupation of East Timor (1975–1999)[edit]

In 1975, the Ford administration, including President Ford himself and Henry Kissinger, authorized and supported Indonesia's invasion and occupation of East Timor.[33][34] Subsequent US administrations continued support of Indonesia while the Indonesian army systematically destroyed East Timor; throughout the 24 year period, the army forcibly sterilized women, carried out massacres, engaged in systematic rape, torture, and food deprivation, destroyed whole villages and forced hundreds of thousands into virtual concentration camps. By 1980 the occupation had left more than 100,000 dead with some estimates running as high as 230,000.[35][36]

The US played a crucial role in supplying weapons to Indonesia. Virtually all of the military equipment used in the invasion was U.S. supplied: U.S.-supplied destroyer escorts shelled East Timor as the attack unfolded; Indonesian marines disembarked from U.S.-supplied landing craft; U.S.-supplied C-47 and C-130 aircraft dropped Indonesian paratroops and strafed Dili with .50 caliber machine guns; while the 17th and 18th Airborne brigades which led the assault on the Timorese capital were "totally U.S. MAP supported," and their jump masters U.S. trained.[37] Following the invasion, U.S. arms sales to Indonesia quadrupled from 1974 to 1975 from $12 million to more than $65 million. U.S. military aid to Jakarta doubled from 1974 to 1976, from $17 million to $40 million. Arms sales dropped to $10–$12 million per year during the last two years of the Ford Administration, but increased $112 million in 1978, and averaged nearly $60 million per year for the duration of the Carter administration.[38]

At the United Nations, American ambassador Daniel Patrick Moynihan undertook the task of blocking Security Council action against East Timor: ""The United States wished things to turn out as they did, and worked to bring this about. The Department of State desired that the United Nations prove utterly ineffective in whatever measures it undertook. This task was given to me, and I carried it forward with no inconsiderable success."Template:cn

International relations professor Ruth Blakely states that "Both the US and Britain were complicit in an ongoing campaign of state terrorism by Indonesia which cost hundreds of thousands of lives. Furthermore, their economies benefited from the sale of arms which were used against East Timorese civilians."[39]

Wars in Indochina[edit]

International relations professor Ruth Blakely stated the following:

- The methods used by the US to defeat its opponents in Indochina involved the widespread use of state terrorism. The US was directly responsible for state terrorism in some cases, as in the aerial bombardment of the civilian population in Korea and the establishment of counterinsurgency programmes such as the Phoenix Programme in Vietnam, which involved torture and assassination of civilians suspected of supporting the opposition, and was intended to deter public support for the enemy. The US was complicit in state terrorism through its support for repressive regimes, either by giving the green light to acts of state terrorism or by providing military hardware to regimes engaged in campaigns of state terrorism, as was the case in Taiwan and Indonesia. The US also collaborated with those regimes through the sharing of military doctrine which advocated state terrorism, as the case of the Philippines shows[39]

Operation Speedy Express was a large-scale, rural "pacification" operation carried out in Vietnam's Mekong Delta (in the province of Kien Hoa) by the United States Army's Ninth Infantry Division. Eight thousand infantrymen were involved in the operation and the division relied heavily on artillery, helicopters gunships and support from B-52 bombers. There were 3,381 tactical air strikes by fighter bombers during Speedy Express. As many as 5,000 noncombatant civilians were killed.[40] Commanding officers encouraged the use of massive, indiscriminate firepower to wrack up high body counts. Louis Janowski, an adviser during Speedy Express,observed the operations and called them a form of 'non selective terrorism': "I have flown Phantom III missions and have medivaced enough elderly people and children to firmly believe that the percentage of Viet Cong killed by support assets is roughly equal to the percentage of Viet Cong in the population", he wrote. "That is, if 8% of the population [of] an area is VC about 8% of the people we kill are VC."[41]

Michael Stohl considers the 1972 saturation bombings of North Vietnam, code-named Operation Linebacker II, to be an example of a type of state terrorism that he calls "terrorism by coercive diplomacy" -- i.e. terrorism whose purpose is to force an opponent to agree to your demands by making their living conditions "horrible beyond endurance".[42]

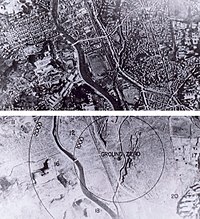

Atomic bombings of Japan (1945)[edit]

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II was the first and last time a state has used nuclear weapons against people. Because concentrated civilian populated areas were targeted, critics hold that it represents the single greatest act of state terrorism in the 20th century even though it was done during wartime. Those who defend the bombings argue that as a result its supposed shortening of the war, thereby preventing any possible need for an invasion, less lives were lost on both sides overall.[43][44]

For scholars and historians, the primary ethics debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,[45] relate to whether the use of the nuclear weapons were justified. Psychologist Chris Stout and former U.S. ambassador Robert Keeley consider the atomic bombings to be a form of state terrorism, based on a definition of terrorism as the targeting of civilians to achieve a political goal.[46][47]

Some scholars have also argued that the bombings weakened moral taboos against attacks on civilians, and allege that this led to such attacks becoming a standard tactic in subsequent US military actions.[48] The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only time nuclear weapons have been used in war.[43][44]

Views and opinions[edit]

According to Thomas Allen, the bombings were part of the overall military strategy to defeat Japan by forcing as quick an end to the war as possible while minimizing loss of life and also avoid a very costly, in terms of both Japanese and Allied casualties, invasion of the Japanese mainland.[49] However, there is considerable debate on the use of nuclear weapons to achieve that military objective that centers on whether killing hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians with such weapons was moral or even necessary, especially the need for a second nuclear bomb to be dropped on Nagasaki.Template:cite

- Viewed as state terrorism

The attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not 'combat' in any of the ways that word is normally used. Nor were they primarily attempts to destroy military targets, for the two cities had been chosen not despite but because they had a high density of civilian housing. Whether the intended audience was Russian or Japanese or a combination of both, then the attacks were to be a show, a display, a demonstration. The question is: What kind of mood does a fundamentally decent people have to be in, what kind of moral arrangements must it make, before it is willing to annihilate as many as a quarter of a million human beings for the sake of making a point?[50]

The just war theorist Michael Walzer argues that while taking the lives of civilians can be justified under conditions of 'supreme emergency', the war situation at that time did not constitute such an emergency and was influenced by the U.S. demand for an unconditional Japanese surrender.[51] Tony Coady, Frances V. Harbour, and Jamal Nassar also view the targeting of civilians during the bombings as a form of terrorism.[3][52]

Richard A. Falk, professor Emeritus of International Law and Practice at Princeton University has written in detail about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as instances of state terrorism. He writes "The graveyards of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the number-one exhibits of state terrorism... Consider the hypocrisy of an Administration that portrays Qaddafi as barbaric while preparing to inflict terrorism on a far grander scale.... Any counter terrorism policy worth the name must include a convincing indictment of the First World variety.".[19][53] He writes elsewhere that:[54]

Undoubtedly the most extreme and permanently traumatizing instance of state terrorism, perhaps in the history of warfare, involved the use of atomic bombs against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in military settings in which the explicit function of the attacks was to terrorize the population through mass slaughter and to confront its leaders with the prospect of national annihilation....the public justification for the attacks given by the U.S. government then and now was mainly to save lives that might otherwise might have been lost in a military campaign to conquer and occupy the Japanese home islands which was alleged as necessary to attain the war time goal of unconditional surrender.... But even accepting the rationale for the atomic attacks at face value, which means discounting both the geopolitical motivations and the pressures to show that the immense investment of the Manhattan Project had struck pay dirt, and disregarding the Japanese efforts to arrange their surrender prior to the attacks, the idea that massive death can be deliberately inflicted on a helpless civilian population as a tactic of war certainly qualifies as state terror of unprecedented magnitude, particularly as the United States stood on the edge of victory, which might well have been consummated by diplomacy. As Michael Walzer puts it, the United States owed the Japanese people 'an experiment in negotiation,' but even if such an initiative had failed there was no foundation in law or morality for atomic attacks on civilian targets.

Steven Poole, author of Unspeak (2006), states in Chapter 6 (entitled 'Terror'), page 130 that:

'Remember that people killed by terrorism are not the people the perpetrators wish to persuade. They are exemplars, bargaining chips. There is a disconnect between victims and audience; the violence is a warning to people other than those targeted. (The writer Brian Jenkins has sumed up this fact in the catchphrase 'terrorism is theatre': a US Army lieutenant colonel went one better, telling a reporter in Baghdad in 2003: 'terrorism is grand theater')[55] Unfortunately this, too, is true of many government actions. Consider the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945. The US had not identified every citizen in those cities as being an indispensable part of the Japanese war effort. On the contrary, the bombings were designed as an awful demonstration: to instil such fear in the Japanese government that they would surrender. The bomb thus spoke thus: Give up or there'll be more where this came from. It also sent a powerful message to a secondary audience: Joseph Stalin. On this measure, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are, by many orders of magnitude, the greatest acts of terrorism in history.'[56]

- Viewed as primarily wartime acts

Burleigh Taylor Wilkins states in Terrorism and Collective Responsibility that "any definition which allowed the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to count as instances of terrorism would be too broad." He goes on to argue "The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while obviously intended by the American government to alter the policies of the Japanese government, seem for all the terror they involved, more an act of war than of terrorism."[57]

It has also been argued, under the view that Japan was involved in a total war, that therefore there was no difference between civilians and soldiers.[58] The targets, while they may not primarily have been chosen for this reason, had, in this view, strategic military value. Hiroshima was used as headquarters of the Fifth Division and the 2nd General Army, which commanded the defense of southern Japan with 40,000 military personal in the city, and was a communication center, a storage point with military factories.[59][60][61] Nagasaki was of wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordinance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.[62]

In 1963, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the subject of a judicial review in Ryuichi Shimoda et al. v. The State.[63] The District Court of Tokyo declined to rule on the legality of nuclear weapons in general, but found that "the attacks upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused such severe and indiscriminate suffering that they did violate the most basic legal principles governing the conduct of war."[64] Francisco Gómez points out in an article published in the International Review of the Red Cross that, with respect to the "anti-city" or "blitz" strategy, that "in examining these events in the light of international humanitarian law, it should be borne in mind that during the Second World War there was no agreement, treaty, convention or any other instrument governing the protection of the civilian population or civilian property." [65]

The possibility that attacks such as those on Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be considered war crimes under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court was one of the major reasons often given by John Bolton (while US ambassador to the United Nations) for the United States not agreeing to be bound by the Rome Statute.[66]

- Viewed as diplomacy or state terrorism not considered

Critical scholarship has focused on the argument that the use of atomic weapons was "primarily for diplomatic purposes rather than for military requirements ... to impress and intimidate the Soviet Union in the emerging Cold War."[67] Certain scholars who oppose the decision to use of the atom bomb, while they state it was unnecessary and immoral, do not claim it was state terrorism per se. Walker's 2005 overview of recent historiography did not discuss the issue of state terrorism.[68]

Forward effects[edit]

Political science professor Michael Stohl and peace studies researcher George A. Lopez, in their book Terrible beyond Endurance? The Foreign Policy of State Terrorism, discuss the argument that the institutionalized form of terrorism carried out by states have occurred as a result of changes that took place following World War II, and in particular the two bombings. In their analysis state terrorism as a form of foreign policy was shaped by the presence and use of weapons of mass destruction, and that the legitimizing of such violent behavior led to an increasingly accepted form of state behavior. They consider both Germany's bombing of London (q.v. The Blitz) and the US atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to be examples of this.

Scholars treating the subject have discussed the bombings within a wider context of the weakening of the moral taboos that were in place prior to World War II, which prohibited mass attacks against civilians during wartime. Mark Selden, professor of sociology and history at Binghamton University and author of War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century, writes, "This deployment of air power against civilians would become the centerpiece of all subsequent U.S. wars, a practice in direct contravention of the Geneva principles, and cumulatively the single most important example of the use of terror in twentieth century warfare."[69] Falk, Selden, and Prof. Douglas Lackey, each of whom relate the Japan bombings to what they believe was a similar pattern of state terrorism in following wars, particularly the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Professor Selden writes: "Over the next half century, the United States would destroy with impunity cities and rural populations throughout Asia, beginning in Japan and continuing in North Korea, Indochina, Iraq and Afghanistan, to mention only the most heavily bombed nations...if nuclear weapons defined important elements of the global balance of terror centered on U.S.-Soviet conflict, "conventional" bomb attacks defined the trajectory of the subsequent half century of warfare."[48]

Cuba (1959–present)[edit]

After Fidel Castro's forces vanquished Fulgencio Batista's forces, a new government was formed in Cuba on January 2, 1959. The CIA initiated a campaign of regime change in the early parts of 1959,[70] and by the spring of 1959 was arming counter-revolutionary guerrillas inside Cuba. By winter of that year US-based Cubans were being supervised by the CIA in the orchestration of bombings and incendiary raids against Cuba.[71] Piero Gleijeses, Jorge I. Dominguez, and Richard Kearney refer to the US actions against Castro during the early 1960s as terrorism. [72][73]

Cuban government officials have accused the United States government of being an accomplice and protector of terrorism against Cuba on many occasions.[74][75] According to Ricardo Alarcón, President of Cuba's national assembly "Terrorism and violence, crimes against Cuba, have been part and parcel of U.S. policy for almost half a century."[76] Testifying before the United States Senate in 1978, Richard Helms, former CIA Director, stated; "We had task forces that were striking at Cuba constantly. We were attempting to blow up power plants. We were attempting to ruin sugar mills. We were attempting to do all kinds of things in this period. This was a matter of American government policy."[77]

The claims formed part of Cuba's $181.1 billion lawsuit in 1999 in Havana's Popular Provincial Tribunal against the United States on behalf of the Cuban people which alleged that for over 40 years, "terrorism has been permanently used by the U.S. as an instrument of its foreign policy against Cuba", and it "became more systematic as a result of the covert action program."[78] The lawsuit detailed a history of terrorism allegedly supported by the United States. The United States has long denied any involvement in the acts named in the lawsuit.[79]

Cuba also claims US involvement in the paramilitary group Omega 7, the CIA undercover operation known as Operation 40, and the umbrella group the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations. Cuban counterterrorism investigator Roberto Hernández testified in a Miami court that the bomb attacks were "part of a campaign of terror designed to scare civilians and foreign tourists, harming Cuba's single largest industry."[81]

In 2001, Cuban Ambassador to the UN Bruno RodrÃguez Parrilla called for UN General Assembly to address all forms and manifestations of terrorism in every corner of the world, including — without exception — state terrorism. He alleged to the UN General Assembly that 3,478 Cubans have died as a result of aggressions and terrorist acts. The Ambassador however did not claim that the US had committed terrorist acts.[82] He also alleged that the United States had provided safe shelter to "those who funded, planned and carried out terrorist acts with absolute impunity, tolerated by the United States Government."[82]

Operation Mongoose[edit]

An objective of the Kennedy administration was the removal of Fidel Castro from power. To this end it implemented Operation Mongoose, a US program of sabotage and other secret operations against the island.[83] Mongoose was led by Edward Lansdale in the Defense Department and William King Harvey at the CIA. Samuel Halpern, a CIA co-organizer, conveyed the breadth of involvement: "CIA and the U. S. Army and military forces and Department of Commerce, and Immigration, Treasury, God knows who else — everybody was in Mongoose. It was a government-wide operation run out of Bobby Kennedy's office with Ed Lansdale as the mastermind."[84] The scope of Mongoose included sabotage actions against a railway bridge, petroleum storage facilities, a molasses storage container, a petroleum refinery, a power plant, a sawmill, and a floating crane. Harvard Historian Jorge DomÃnguez stated that "only once in [the] thousand pages of documentation did a U.S. official raise something that resembled a faint moral objection to U.S. government sponsored terrorism." [85] The CIA operation was based in Miami, Florida and among other aspects of the operation, enlisted the help of the Mafia to plot an assassination attempt against Fidel Castro, the Cuban president; for instance, William Harvey was one of the CIA case officers who directly dealt with the mafiosi John Roselli.[86]

Dominguez wrote that Kennedy put a hold on Mongoose actions as the Cuban Missile Crisis escalated, and the "Kennedy administration returned to its policy of sponsoring terrorism against Cuba as the confrontation with the Soviet Union lessened." [85] However, Chomsky argued that "terrorist operations continued through the tensest moments of the missile crisis," remarking that "they were formally canceled on October 30, several days after the Kennedy and Khrushchev agreement, but went on nonetheless." Accordingly, "the Executive Committee of the National Security Council recommended various courses of action, "including ‘using selected Cuban exiles to sabotage key Cuban installations in such a manner that the action can plausibly be attributed to Cubans in Cuba’ as well as ‘sabotaging Cuban cargo and shipping, and [Soviet] Bloc cargo and shipping to Cuba." [71] Peter Kornbluh, senior analyst at the National Security Archive at George Washington University, raised the point that according to the documentary record, directly after the first executive committee (EXCOMM) meeting that was held on the missile crisis, Attorney General Robert Kennedy "convened a meeting of the Operation Mongoose team" expressing disappointment in its results and pledging to take a closer personal attention on the matter. Kornbluh accused RFK of taking "the most irrational position during the most extraordinary crisis in the history of U. S. foreign policy", remarking that "Not to belabor the obvious, but for chrissake, a nuclear crisis is happening and Bobby wants to start blowing things up.".[87]

Historian Stephen G. Rabe wrote that "scholars have understandably focused on...the Bay of Pigs invasion, the U.S. campaign of terrorism and sabotage known as Operation Mongoose, the assassination plots against Fidel Castro, and, of course, the Cuban missile crisis. Less attention has been given to the state of U.S.-Cuban relations in the aftermath of the missile crisis." In contrast Rabe wrote that reports from the Church Committee reveal that from June 1963 onward the Kennedy administration intensified its war against Cuba while the CIA integrated propaganda, "economic denial", and sabotage to attack the Cuban state as well as specific targets within.[88] One example cited is an incident where CIA agents, seeking to assassinate Castro, provided a Cuban official, Rolando Cubela Secades, with a ballpoint pen rigged with a poisonous hypodermic needle.[88] At this time the CIA received authorization for thirteen major operations within Cuba; these included attacks on an electric power plant, an oil refinery, and a sugar mill.[88] Rabe has written that the "Kennedy administration...showed no interest in Castro's repeated request that the United States cease its campaign of sabotage and terrorism against Cuba. Kennedy did not pursue a dual-track policy toward Cuba....The United States would entertain only proposals of surrender." Rabe further documents how "Exile groups, such as Alpha 66 and the Second Front of Escambray, staged hit-and-run raids on the island...on ships transporting goods...purchased arms in the United States and launched...attacks from the Bahamas." [88]

Author Joan Didion has emphasized that despite the Kennedy administration's rejection of the "two track strategy," such a strategy did in effect continue for much time afterwards, characterized by the FBI being consistently engaged in investigating and prosecuting groups such as Omega 7, while the same groups received funds, arms, and support from the CIA. Eventually, in 1985, the leader of Omega 7, Eduardo Arocena, was successfully prosecuted for murder with the aid of an FBI investigation[89]. The extent of CIA involvement in these groups has been debated by historians, and Didion relates that some of these groups were more rogue due to a distrust of the CIA. Later terrorist acts by ex-CIA operatives from the Cuba project, such as the CORU group's bombing of Cubana Flight 455 in 1976, were most likely carried out without CIA planning or knowledge as far as the public record shows.

Allegations of harboring terrorists[edit]

The Cuban revolution resulted in a large Cuban refugee community in the U.S., some of whom have conducted long-term insurgency campaigns against Cuba.[90] and conducted training sessions at a secluded camp near the Florida Everglades. These efforts are charged to have been directly supported initially by the United States government.[91] The failed military invasion of Cuba during the administration of John F. Kennedy at the Bay of Pigs marked the end of documented U.S. involvement.

The Cuban Government, its supporters and some outside observers have charged that the group Alpha 66, whose former secretary general Andrés Nazario Sargén acknowledged terrorist attacks on Cuban tourist spots in the 1990s[90] and conducted training sessions at a secluded camp near the Florida Everglades,[92] has, according to Cuba's official newspaper Granma, been supported by the National Endowment for Democracy, the United States Agency for International Development and, more directly, the CIA.

Marcela Sanchez says that the U.S. has also failed to indict or prosecute the alleged terrorists Guillermo and Ignacio Novo Sampoll, Pedro Remon, and Gaspar Jimenez.[80][93] Claudia Furiati has suggested Sampol was linked to President Kennedy's assassination and plans to kill President Castro.[94]

Luis Posada Carriles a former CIA operative, Posada has been convicted in absentia of involvement in various terrorist attacks and plots in the Western hemisphere, including involvement in the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed seventy-three people[95][96] and has admitted to his involvement in other terrorist plots including a string of bombings in 1997 targeting fashionable Cuban hotels and nightspots.[97][98][99] In addition, he was jailed under accusations related to an assassination attempt on Fidel Castro in Panama in 2000, although he was later pardoned by Panamanian President Mireya Moscoso in the final days of her term.[100][101]

In 2005, Posada was held by U.S. authorities in Texas on the charge of illegal presence on national territory before the charges were dismissed on May 8, 2007. His release on bail on April 19, 2007 had elicited angry reactions from the Cuban and Venezuelan governments.[102] The U.S. Justice Department had urged the court to keep him in jail because he was "an admitted mastermind of terrorist plots and attacks", a flight risk and a danger to the community.[99]

On September 28, 2005 a U.S. immigration judge ruled that Posada cannot be deported, finding that he faces the threat of torture in Venezuela.[103]

Posada Carrilles is currently standing trial in El Paso, Texas, for lying to immigration authorities. The trial has been criticized internationally for not being a murder trial. However, the Obama administration's Department of Justice did add several counts to the perjury charge, relating to Posada's history of terrorism. In specific, he is accused of lying to immigration authorities about his admitted role in the 1997 tourism bombings in Cuba.

Nicaragua (1979–90)[edit]

- See also: Iran-Contra affair

Following the rise to power of the left-wing Sandinista government in Nicaragua, the Ronald Reagan administration ordered the CIA to organize and train the Contras, a right wing guerrilla group. On December 1, 1981, President Reagan signed an initial, one-paragraph "Finding" authorizing the CIA's paramilitary war against Nicaragua.[104]

The Republic of Nicaragua vs. The United States of America[105] was a case heard in 1986 by the International Court of Justice which found that the United States had violated international law by direct acts of U.S. personnel and by the supporting Contra guerrillas in their war against the Nicaraguan government and by mining Nicaragua's harbors. The US was not imputable for possible human rights violations done by the Contras. The Court found that this was a conflict involving military and para-military forces and did not make a finding of state terrorism.

Florida State University professor, Frederick H. Gareau, has written that the Contras "attacked bridges, electric generators, but also state-owned agricultural cooperatives, rural health clinics, villages and non-combatants." U.S. agents were directly involved in the fighting. "CIA commandos launched a series of sabotage raids on Nicaraguan port facilities. They mined the country's major ports and set fire to its largest oil storage facilities." In 1984 the U.S. Congress ordered this intervention to be stopped, however it was later shown that the CIA illegally continued (See Iran-Contra affair). Professor Gareau has characterized these acts as "wholesale terrorism" by the United States.[106]

In 1984 a CIA manual for training the Nicaraguan Contras in psychological operations was leaked to the media, entitled "Psychological Operations in Guerrilla War".[107]

The manual recommended "selective use of violence for propagandistic effects" and to "neutralize" government officials. Nicaraguan Contras were taught to lead:

...selective use of armed force for PSYOP psychological operations effect.... Carefully selected, planned targets — judges, police officials, tax collectors, etc. — may be removed for PSYOP effect in a UWOA unconventional warfare operations area, but extensive precautions must insure that the people "concur" in such an act by thorough explanatory canvassing among the affected populace before and after conduct of the mission.—James Bovard, Freedom Daily[108]

Former State Department official William Blum, has written that "American pilots were flying diverse kinds of combat missions against Nicaraguan troops and carrying supplies to contras inside Nicaraguan territory. Several were shot down and killed. Some flew in civilian clothes, after having been told that they would be disavowed by the Pentagon if captured. Some contras told American congressmen that they were ordered to claim responsibility for a bombing raid organized by the CIA and flown by Agency mercenaries."[109] According to Blum the Pentagon considered U.S. policy in Nicaragua to be a "blueprint for successful U.S. intervention in the Third World" and it would go "right into the textbooks".[110]

Colombian writer and former diplomat Clara Nieto, in her book "Masters of War", charged the Reagan administration was "the paradigm of a terrorist state", remarking that this was "ironically, the very thing Reagan claimed to be fighting." Nieto charged direct CIA involvement, claiming that "the CIA launched a series of terrorist actions from the "mothership" off Nicaragua's coast. In September 1983, she charged the agency attacked Puerto Sandino with rockets. The following month, frogmen blew up the underwater oil pipeline in the same port- the only one in the country. In October there was an attack on Pierto Corinto, Nicaragua's largest port, with mortars, rockets and grenades, blowing up five large oil and gasoline storage tanks. More than a hundred people were wounded, and the fierce fire, which could not be brought under control for two days, forced the evacuation of 23,000 people." [111]

Historian Greg Grandin described a disjuncture between official U.S. ideals and support for terrorism. "Nicaragua, where the United States backed not a counter insurgent state but anti-communist mercenaries, likewise represented a disjuncture between the idealism used to justify U.S. policy and its support for political terrorism... The corollary to the idealism embraced by the Republicans in the realm of diplomatic public policy debate was thus political terror. In the dirtiest of Latin America's dirty wars, their faith in America's mission justified atrocities in the name of liberty." [112] In his analysis, Grandin charged that the behaviour of the U.S. backed-contras was particularly inhumane and vicious: "In Nicaragua, the U.S.-backed Contras decapitated, castrated, and otherwise mutilated civilians and foreign aid workers. Some earned a reputation for using spoons to gorge their victims eye's out. In one raid, Contras cut the breasts of a civilian defender to pieces and ripped the flesh off the bones of another." [113]

Nicaragua vs. United States[edit]

The Republic of Nicaragua vs. The United States of America[105] was a case heard in 1986 by the International Court of Justice which ruled in Nicaragua's favor, and found that the United States had violated international law. The court ruled that the U.S. was "in breach of its obligation under customary international law not to use force against another state" by direct acts of U.S. personnel and by the supporting Contra guerrillas in their war against the Nicaraguan government and by mining Nicaragua's harbors. The ICJ ordered the U.S. to pay reparations. The US was not imputable for possible human rights violations done by the Contras. The case led to considerable debate concerning the issue of the extent to which state support of terrorists implicates the state itself.[114] A consensus among scholars of international law had not been reached by the mid-2000s.[114]

U.S. foreign policy critic Noam Chomsky argued that the U.S. was legally found guilty of international terrorism based on this verdict.[115][116]

The World Court considered their case, accepted it, and presented a long judgment, several hundred pages of careful legal and factual analysis that condemned the United States for what it called "unlawful use of force" — which is the judicial way of saying "international terrorism" — ordered the United States to terminate the crime and to pay substantial reparations, many billions of dollars, to the victim.—Noam Chomsky, interview on Pakistan Television[117]

The essence of this view of U.S. actions in Nicaruaga was supported by Oscar Schachter: "[W]hen a government provides weapons, technical advice, transportation, aid and encouragement to terrorists on a substantial scale it is not unreasonable to conclude that the armed attack is imputable to that government."[114]

Guatemala (1954–96)[edit]

Professor of History, Stephen G. Rabe, wrote "in destroying the popularly elected government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman (1950-1954), the United States initiated a nearly four-decade-long cycle of terror and repression" [118]

After the U.S.-backed coup, which toppled president Jacobo Arbenz, lead coup plotter Castillo Armas assumed power. Author and university professor, Patrice McSherry argued that with Armas at the head of government, "the United States began to militarize Guatemala almost immediately, financing and reorganizing the police and military."[119]

In his book "State Terror and Popular Resistance in Guatemala", Michael McClintock[120] argued that the national security apparatus Armas presided over was "almost entirely oriented toward countering subversion," and that the key component of that apparatus was "an intelligence system set up by the United States."[121] At the core of this intelligence system were records of communist party members, pro-Arbenz organizations, teacher associations, and peasant unions which were used to create a detailed "Black List" with names and information about some 70,000 individuals that were viewed as potential subversives. It was "CIA counter-intelligence officers who sorted the records and determined how they could be put to use."[122] McClintock argues that this list persisted as an index of subversives for several decades and probably served as a database of possible targets for the counter-insurgency campaign that began in the early 1960s.[123] McClintock wrote:

United States counter-insurgency doctrine encouraged the Guatemalan military to adopt both new organizational forms and new techniques in order to root out insurgency more effectively. New techniques would revolve around a central precept of the new counter-insurgency: that counter insurgent war must be waged free of restriction by laws, by the rules of war, or moral considerations: guerrilla "terror" could be defeated only by the untrammeled use of "counter-terror", the terrorism of the state.—Michael McClintock[124]

McClintock wrote that this idea was also articulated by Colonel John Webber, the chief of the U.S. Military Mission in Guatemala, who instigated the technique of "counter-terror." Colonel Webber defended his policy by saying, "That's the way this country is. The Communists are using everything they have, including terror. And it must be met."[125]

Utilizing declassified government documents, researchers Kate Doyle and Carlos Osorio from the research institute the National Security Archive documented that Guatemalan Colonel Byron Lima Estrada took military police and counterintelligence courses at the School of the Americas. He later served in several elite counterinsurgency units trained and equipped by the U.S. Military Assistance Program (MAP). He eventually rose to command D-2, the Guatemalan Military Intelligence services who were responsible for many of the terror tactics wielded throughout the 1980s.[126]

School of the Americas[edit]

Professor Gareau argued that the School of the Americas at Fort Benning (reorganized in 2001 as Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation), a U.S. training institution mainly for Latin American state security officials, is a terrorist training ground. He cited a UN report which states the school has "graduated 500 of the worst human rights abusers in the hemisphere." Gareau alleges that by funding, training and supervising Guatemalan 'Death Squads' Washington was complicit in state terrorism.[127]

Defenders of the school[who?] argued that the alleged connection to human rights abusers is often weak. For example, Roberto D'Aubuisson's sole link to the SOA is that he had taken a course in Radio Operations long before El Salvador's civil war began.[128] They also argued that no school should be held accountable for the actions of only some of its many graduates. Before coming to the current WHINSEC each student is now "vetted" by his/her nation and the U.S. embassy in that country. All students are now required to receive "human rights training in law, ethics, rule of law and practical applications in military and police operations."[129][130][131]

Chile[edit]

Michael Stohl and George A. Lopez have accused the United States of supporting and committing State Terrorism in the period 1970-1973, during the overthrow of the socialist elected Chilean government of Salvador Allende. Stohl wrote, "In addition to nonterroristic strategies...the United States embarked on a program to create economic and political chaos in Chile...After the failure to prevent Allende from taking office, efforts shifted to obtaining his removal." Money authorized for the CIA to destabilize Chilean society, included, "financing and assisting opposition groups and right-wing terrorist paramilitary groups such as Patria y Libertad ("Fatherland and Liberty")." Project FUBELT was the codename for the secret CIA operations to undermine Salvador Allende's government and promote a military coup in Chile. In September 1973 the Allende government was overthrown in a violent military coup in which the United States is claimed to have been "intimately involved." [132]

Professor Gareau, wrote on the subject: "Washington's training of thousands of military personnel from Chile who later committed state terrorism again makes Washington eligible for the charge of accessory before the fact to state terrorism. The CIA's close relationship during the height of the terror to Contreras, Chile's chief terrorist (with the possible exception of Pinochet himself), lays Washington open to the charge of accessory during the fact." Gareau argued that the fuller extent involved the US taking charge of coordinating counterinsurgency efforts between all Latin American countries. He wrote, "Washington's service as the overall coordinator of state terrorism in Latin America demonstrates the enthusiasm with which Washington played its role as an accomplice to state terrorism in the region. It was not a reluctant player. Rather it not only trained Latin American governments in terrorism and financed the means to commit terrorism; it also encouraged them to apply the lessons learned to put down what it called "the communist threat." Its enthusiasm extended to coordinating efforts to apprehend those wanted by terrorist states who had fled to other countries in the region....The evidence available leads to the conclusion that Washington's influence over the decision to commit these acts was considerable."[133] "Given that they knew about the terrorism of this regime, what did the elites in Washington during the Nixon and Ford administrations do about it? The elites in Washington reacted by increasing U.S. military assistance and sales to the state terrorists, by covering up their terrorism, by urging U.S. diplomats to do so also, and by assuring the terrorists of their support, thereby becoming accessories to state terrorism before, during, and after the fact." [134]

Thomas Wright charged that Chile was an example of State Terrorism of a very open kind that did not attempt a facade of civilian governance, and that had a "September 11th effect" through the hemisphere. Wright, argued that "unlike their Brazilian counterparts, they did not embrace state terrorism as a last recourse; they launched a wave of terrorism on the day of the coup. In contrast to the Brazilians and Uruguayans, the Chileans were very public about their objectives and their methods; there was nothing subtle about rounding up thousands of prisoners, the extensive use of torture, executions following sham court-marshal, and shootings in cold blood. After the initial wave of open terrorism, the Chilean armed forces constructed a sophisticated apparatus for the secret application of state terrorism that lasted until the dictatorship's end...The impact of the Chilean coup reached far beyond the country's borders. Through their aid in the overthrow of Allende and their support of the Pinochet dictatorship, President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, sent a clear signal to all of Latin America that anti-revolutionary regimes employing repression, even state terrorism, could count on the support of the United States. The U.S. government in effect, gave a green light to Latin America's right wing and its armed forces to eradicate the left and use repression to erase the advances that workers — and in some countries, campesinos — had made through decades of struggle. This "September 11 effect" was soon felt around the hemisphere." [135]

Prof. Gareau concluded, "The message for the populations of Latin American nations and particularly the Left opposition was clear: the United States would not permit the continuation of a Socialist government, even if it came to power in a democratic election and continued to uphold the basic democratic structure of that society."[134]

Iran (1979–present)[edit]

In 2007, an article in the Asia Times Online asserted that the United States has likely ramped up support for Iran's oppressed minorities in an attempt to push the Iranian regime toward a negotiated settlement over Iraq." [136] An Asian Times article notes that "Iranian officials have repeatedly accused the United States and Britain of provoking ethnic unrest in Iran and of supporting opposition groups."[137]

Jundullah[edit]

The Sunni militant organization Jundallah has been identified as a terrorist organization by Iran and Pakistan.[138][139] According to an April 2007 report by Brian Ross and Christopher Isham of ABC News, the United States government had been secretly encouraging and advising the Jundullah in its attacks against Iranian targets. This support is said to have started in 2005 and arranged so that the United States provided no direct funding to the group, which would require congressional oversight and attract media attention.[140] The report was denied by Pakistan official sources.[141][142]

Fars News Agency, an Iranian state run news agency, alleged that the United States government is involved in the terrorist acts of the Peoples Resistant Movement of Iran (PRMI). The Voice of America, the official broadcasting service of the United States government, interviewed Jundullah leader Abdul Malik Rigi in April 2007, and the Iranian government claims that the fact that he was interviewed was proof of US terrorism.[143]

People's Mujahedin of Iran[edit]

The People's Mujahedin of Iran, PMOI, known also as the Mujahedeen-e Khalq or MEK, is dedicated to the overthrow of the Iranian regime. Iranian government has accused the MEK of orchestrating a series of bombings inside Iran, including one attack that left the current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, partially paralyzed. Until January, 2009 the United States military protected the MEK inside its military camp and on supply runs to Baghdad, although the U.S. has listed the group as a terrorist organization since 1997.[144]

"They're terrorists only when we consider them terrorists. They might be terrorists in everybody else's books . . . . It was a strange group of people and the leadership was extremely cruel and extremely vicious." said Lawrence Wilkerson, former Secretary of State Colin Powell's chief of staff.[144]

In April 2007, CNN reported that the US military and the International Committee of the Red Cross were protecting the People's Mujahedin of Iran, with the US army regularly escorting PMOI supply runs between Baghdad and its base, Camp Ashraf.[145] The PMOI have been designated as a terrorist organization by the United States (since 1997), Canada, and Iran.[146][147] According to the Wall Street Journal[148] "senior diplomats in the Clinton administration say the PMOI figured prominently as a bargaining chip in a bridge-building effort with Tehran." The PMOI is also on the European Union's blacklist of terrorist organizations, which lists 28 organizations, since 2002.[149] The enlistments included: Foreign Terrorist Organization by the United States in 1997 under the Immigration and Nationality Act, and again in 2001 pursuant to section 1(b) of Executive Order 13224; as well as by the European Union (EU) in 2002.[150] Its bank accounts were frozen in 2002 after the September 11 attacks and a call by the EU to block terrorist organizations' funding. However, the European Court of Justice has overturned this in December 2006 and has criticized the lack of "transparency" with which the blacklist is composed.[151] However, the Council of the EU declared on 30 January 2007 that it would maintain the organization on the blacklist.[152][153] The EU-freezing of funds was lifted on December 12, 2006 by the European Court of First Instance.[154] In 2003 the US State Department included the NCRI on the blacklist, under Executive Order 13224.[155]

According to a 2003 article by the New York Times, the US 1997 proscription of the group on the terrorist blacklist was done as "a goodwill gesture toward Iran's newly elected reform-minded president, Mohammad Khatami" (succeeded in 2005 by the more conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad).[156] In 2002, 150 members of the United States Congress signed a letter calling for the lifting of this designation.[157] The PMOI have also tried to have the designation removed through several court cases in the U.S. The PMOI has now lost three appeals (1999, 2001 and 2003) to the US government to be removed from the list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations, and its terrorist status was reaffirmed each time. The PMOI has continued to protest worldwide against its listing, with the overt support of some US political figures.[158][159]

Past supporters of the PMOI have included Rep. Tom Tancredo (R-CO), Rep. Bob Filner, (D-CA), and Sen. Kit Bond (R-MO), and former Attorney General John Ashcroft, "who became involved with the [PMOI] while a Republican senator from Missouri."[160][161] In 2000, 200 U.S. Congress members signed a statement endorsing the organization's cause.[162]

Iraq (1992–1995)[edit]

The New York Times reported that, according to former U.S. intelligence officials, the CIA once orchestrated a bombing and sabotage campaign between 1992 and 1995 in Iraq via one of the resistance organizations, Iyad Allawi's group in an attempt to destabilize the country. According to the Iraqi government at the time, and one former CIA officer, the bombing campaign against Baghdad included both government and civilian targets. According to this former CIA official, the civilian targets included a movie theater and a bombing of a school bus where children were killed. No public records of the secret bombing campaign are known to exist, and the former U.S. officials said their recollections were in many cases sketchy, and in some cases contradictory. "But whether the bombings actually killed any civilians could not be confirmed because", as a former CIA official said, "the United States had no significant intelligence sources in Iraq then."[163][164]

Lebanon (1985)[edit]

The investigative reporter Bob Woodward has accused the CIA of arranging for Saudi Arabia to sponsor a 1985 Beirut car bombing which killed 81 people. The bombing was apparently an assassination attempt on an Islamic cleric, Sheikh Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah.[165][166] The bombing, known as the Bir bombing after Bir el-Abed, the impoverished Beirut neighborhood in which it had occurred, was reported by the New York Times to have caused a "massive" explosion "even by local standards", killing 81 people, and wounding more than 200.[167] Investigative journalist Bob Woodward stated that the CIA was funded by the Saudi Arabian government to arrange the bombing.[166][168] Fadlallah himself also claims to have evidence that the CIA was behind the attack and that the Saudis paid $3 million.[169]

The U.S. National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane admitted that those responsible for the bomb may have had American training, but that they were "rogue operative(s)" and the CIA in no way sanctioned or supported the attack.[170] Roger Morris wrote in the Asia Times that the next day, a notice hung over the devastated area where families were still digging the bodies of relatives out of the rubble. It read: "Made in the USA". The terrorist strike on Bir el-Abed is seen as a product of U.S. covert policy in Lebanon. Agreeing with the proposals of CIA director William Casey, president Ronald Reagan sanctioned the Bir attack in retaliation for the truck-bombing of the U.S. Marine Corps barracks at Beirut airport in October 1983, which, Roger Morris alleges, in turn had been a reprisal for earlier U.S. acts of intervention and diplomatic dealings in Lebanon's civil war that had resulted in hundreds of Lebanese and Palestinian lives. After CIA operatives had repeatedly failed to arrange Casey's car-bombing, the CIA allegedly "farmed out" the operation to agents of its longtime Lebanese client, the Phalange, a Maronite Christian, anti-Islamic militia.[167] Others allege the 1984 Bombing of the U.S. Embassy annex northeast of Beirut as the motivating factor.[170]

Philippines[edit]

In "The Terrorist Foundations of US Foreign Policy", Professor of International Law Richard Falk argues that during the Spanish American War, when the U.S. was "confronted by a nationalistic resistance movement in the Philippines," American forces were responsible for state terrorism. Falk relates that "as with the wars against native American peoples, the adversary was demonized (and victimized). In the struggle, US forces, with their wide margin of military superiority, inflicted disproportionate casualties, almost always a sign of terrorist tactics, and usually associated with refusal or inability to limit political violence to a discernible military opponent. The dispossession of a people from their land almost always is a product of terrorist forms of belligerency. In contrast, interventions in Central and South America in the area of so-called "Gunboat Diplomacy" were generally not terrorist in character, as little violence was required to influence political struggle for ascendancy between competing factions of an indigenous elite." [171]

In "Instruments of Statecraft" [4], human rights researcher Michael McClintock described the intensification of the U.S. role during the Hukbalahap rebellion in 1950, when concerns about a perceived communist-led Huk insurgency prompted sharp increases in military aid and a reorganization of tactics towards methods of guerrilla warfare. McClintock describes the role of U.S. "advisers" to the Philippine Minister of National Defense, Ramon Magsaysay, remarking that they "adroitly managed Magsaysay's every move." Air Force Lt. Col. Edward Geary Lansdale was a psywar propaganda specialist who became the close personal adviser and confidant of Magsaysay. The forte of another key adviser, Charles Bohannan, was guerrilla warfare. McClintock cites several examples to demonstrate that "terror played an important part" in the psychological operations under U.S. guidance. Those psywar operations that utilized terror included theatrical displays involving the exemplary display of dead Huk bodies in an effort to incite fear in rural villagers. In another psywar operation described by Lansdale, Philippine troops engaged in nocturnal captures of individual Huks. They punctured the necks of the victims and drained the corpses of blood, leaving the bodies to be discovered when daylight came, so as to play upon fears associated with the local folklore of the Asuang, or vampire. [172]

For McClintock, this Philippines episode is particularly important because of its formative influence on U.S. counterinsurgency doctrine. In his essay, American Doctrine and State Terror, McClintock explained that U.S. Army instruction manuals of the 1960s concerning 'counterterrorism' often referred to "the particular experiences of the Philippines and Vietnam." Noting that tactics similar to those used during the Huk Rebellion (from 1946–54) in the Philippines were cited in the manuals, he elaborated that the "Department of the Army's 1976 psywar publication, DA Pamphlet 525-7-1, refers to some of the classic counterterror techniques and account of the practical application of terror. These include the capture and murder of suspected guerillas in a manner suggesting the deed was done by legendary vampires (the 'asuang'); and a prototypical "Eye of God" technique in which a stylized eye would be painted opposite the house of a suspect."[173]

See also[edit]

| You can help Anarchopedia by expanding this article by adding some of terrorism and the United States these quotes from Wikiquote |

- Human rights in the United States

- List of military interventions of the United States

- Operation Northwoods

- Wikipedia:War crimes and the United States

- Wikipedia:Torture and the United States

- Wikipedia:CIA sponsored regime change

- Wikipedia:Overseas expansion of the United States

- Wikipedia:Overseas interventions of the United States

- Wikipedia:American imperialism

- Wikipedia:United States military aid

- Wikipedia:United States Foreign Military Financing

- Wikipedia:United States Agency for International Development

References[edit]

- ↑

- Ball, Matthew (2004). Terroris, Human rights, Social justice, Freedom and Democracy: some considerations for the legal and justice professionals of the ‘Coalition of the Willing’. QUT Law & Justice Journal. Archived from source 2010-01-26. URL accessed on 2008-02-14.

- The role of lawyers in defending the democratic rights of the people. International Association of People's Lawyers. Archived from source 2008-04-08. URL accessed on 2008-02-14.

- San Juan, Jr., E. Filipina Militants Indict Bush-Arroyo for Crimes Against Humanity. Asian Human Rights Commission. URL accessed on 2007-07-09.

- Venezuelan Leader Lashes at US in UN Speech. Agence France-Presse. Archived from source 2008-02-13. URL accessed on 2008-02-14.

- "Security Council considers Nicaraguan complaint against United States, takes no action". United Nations. November, 1986. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1309/is_v23/ai_4656176. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- San Juan, Jr., E. Class Struggle and Socialist Revolution in the Philippines: Understanding the Crisis of U.S. Hegemony, Arroyo State Terrorism, and Neoliberal Globalization. Monthly Review Foundation. URL accessed on 2007-07-09.

- Simbulan, Roland G. The Real Threat. Seminar. URL accessed on 2007-07-09.

- Piszkiewicz, Dennis (November 30, 2003). Terrorism's War with America: A History, p. 224, Praeger Publishers.

- Cohn, Marjorie Understanding, responding to, and preventing terrorism. (Reprint) Arab Studies Quarterly. URL accessed on 2007-07-09.

- Halliday, Dennis The UN and its conduct during the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Centre for Research on Globalization. URL accessed on 2007-07-09.

- Template:Cite episode

</li>

- ↑ Michael Howard, George J. Andreopoulos, Mark R. Shulman (1997). The Laws of War: Constraints on Warfare in the Western World, Yale University Press. "Michael Walzer has argued that Hiroshima was not a case of supreme emergency, but rather an act of political terror."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tony Coady. A just cause doesn't excuse indiscriminate killing. The Age. URL accessed on 2010-05-12.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Annamarie Oliverio (1998). The state of terror, SUNY Press.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam The United States is a Leading Terrorist State.

- ↑ POLITICS: U.N. Member States Struggle to Define Terrorism

- ↑ Understanding terrorism: challenges, perspectives, and issues, by Gus Martin, SAGE, 2006, ISBN 1412927226. at [1], p. 111

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 A History of Terrorism, by Walter Laqueur, Transaction Publishers, 2007, ISBN 0765807998, at [2], p. 6

- ↑ terrorism. Encyclopædia Britannica. URL accessed on 2009-03-25.

- ↑ Terrorism. Encyclopædia Britannica. URL accessed on 2009-03-25.

- ↑ The Superpowers and International Terror Michael Stohl, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association, Atlanta, March 27-April 1, 1984).

- ↑ Stohl, National Interests and State Terrorism, The Politics of Terrorism, Marcel Dekker 1988, p.275

- ↑ Arno Mayer, "Untimely reflections upon the state of the world", guest column in the Daily Princetonian, October 5, 2001; also see George, Alexander, ed. "Western State Terrorism",1 and Selden, Mark, ed. "War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century", 13.

- ↑ Democracy Now! Noam Chomsky Speech On State Terror and U.S. Foreign Policy

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Barsamian, David The United States is a Leading Terrorist State. Monthly Review. URL accessed on 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Military Operations in Low Intensity Conflict, Headquarters Departments of the Army and Air Force.

- ↑ [www.middlebury.edu/media/view/214721/original/OdomPaper.pdf American Hegemony: How to Use It, How to Lose It by Gen. William Odom]

- ↑ American Hegemony How to Use It, How to Lose at Docstoc

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Falk, Richard (1988). Revolutionaries and Functionaries: The Dual Face of Terrorism, Dutton.

- ↑ Falk, Richard Gandhi, Nonviolence and the Struggle Against War. The Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research. URL accessed on 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Richard, ({{{year}}}). "Thinking About Terrorism," The Nation, 242, 873–892.

- ↑ "The Politics of Violence", Daniel Schorr, 1 May 1988.

- ↑ Quoted in Cahill, Kevin M. (2003). Traditions, values, and humanitarian action, Fordham University Press.

- ↑ Robert Cribb, ed. The Indonesian Killings of 1965-1966: Studies from Java and Bali (Clayton, Vic: Monash papers on Southeast Asia, no. 21, 1990), p.12

- ↑ US National Archives, RG 59 Records Department of State: cable no. 868, ref: Embtel 852, October 5, 1965.

- ↑ San Francisco Examiner, May 20, 1990

- ↑ San Francisco Examiner, May 20, 1990; Washington Post, May 21, 1990.

- ↑ Kadane, Kathy (1990-05-20). "Ex-agents say CIA compiled death lists for Indonesians". San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco).

</li>

- ↑ Telegram, Embassy in Indonesia to Department of State, Jakarta, 2 December 1965, FRUS 64-68, 379; 379-80.

- ↑ Kathy Kadane… A Letter to the Editor, New York Review of Books, April 10, 1997

- ↑ Historian Claims West Backed Post-Coup Mass Killings in ’65, Jakarta Globe

- ↑ Blakely, Ruth (2009). State terrorism and neoliberalism: the North in the South, Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB62/doc4.pdf (pg.9-10)

- ↑ East Timor Revisited. Ford, Kissinger and the Indonesian Invasion, 1975-76 The National Security Archive

- ↑ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB62/#18

- ↑ http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/35878.htm

- ↑ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB174/1010.pdf

- ↑ http://www.worldpolicy.org/projects/arms/reports/indoarms.html

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Blakely, Ruth (2009). State terrorism and neoliberalism: the North in the South, Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ "Pacification's Deadly Price", Newsweek (June 19, 1972), pp.42-43.

- ↑ A My Lai a Month Turse, Nick. thenation.com.

- ↑ Stohl, Michael (1988). The Politics of Terrorism, CRC Press.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Frey, Robert S. (2004). The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond, University Press of America. ISBN 0761827439. Reviewed at: Sarah, (2005). "The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond (Review)," Harvard Human Rights Journal, 18, .

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 John, (1995). "The Bombed: Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Memory," Diplomatic History, 19, .

- ↑ See: J. Samuel, (2005). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground," Diplomatic History, 29, 334.

- ↑ Chris E. Stout, {{{first}}} (2002). The Psychology of Terrorism: Clinical aspects and responses Psychological dimensions to war and peace, 105–7. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ↑ Robert V. Keeley, {{{first}}} (December 2002). Trying to Define Terrorism, 33–39 [35]. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Selden, War and State Terrorism.

- ↑ Allen, Thomas; Norman Polmar (1995). Code-Name Downfall, p. 266–270, New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Hiroshima; Breaking the Silence. Archived from source 2007-12-01. URL accessed on 2008-01-30.

- ↑ Simon Caney (2006). Justice Beyond Borders: A Global Political Theory, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jamal Nassar (2009). Globalization and Terrorism: The Migration of Dreams and Nightmares, Rowman & Littlefield. "As discussed earlier, the Holocaust, followed by the Allied firebombings of Dresden and Tokyo and the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, represented some of the most severe effects of terrorism directed at civilian populations."

- ↑ Falk, Richard Gandhi, Nonviolence and the Struggle Against War. The Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research. URL accessed on 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Falk, Richard. "State Terror versus Humanitarian Law",in Selden,, Mark, editor (November 28, 2003). War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.. ISBN 978-0742523913. ,45

- ↑ Danner, Mark "Delusions in Baghdad", New York Review of Books, 19 November 2003

- ↑ 2006 Poole, Steven 'Unspeak', Little Brown, London. ISBN 0 316 73100 5

- ↑ Wilkins, Burleigh Taylor. Terrorism and Collective Responsibility, p. 11, Routledge.

- ↑ The Avalon Project : The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. URL accessed on 2005-08-06.

- ↑ Hiroshima Before the Bombing. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. URL accessed on 2008-03-16.

- ↑ Hanson, Victor Davis 60 Years Later: Considering Hiroshima. National Review. URL accessed on 2008-03-24.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Hubertus Hiroshima: Hubertus Hoffmann meets the only U.S. Officer on both A-Missions and one of his Victims.

- ↑ The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima.

- ↑ Shimoda et al. v. The State, Tokyo District Court, 7 December 1963

- ↑ Falk, Richard A. (1965-02-15). "The Claimants of Hiroshima". The Nation. reprinted in (1966) "The Shimoda Case: Challenge and Response" Richard A. Falk, Saul H. Mendlovitz eds. The Strategy of World Order. Volume: 1, p. 307–13, New York: World Law Fund. </li>

- ↑ International Review of the Red Cross no 323, p.347-363 The Law of Air Warfare (1998)

- ↑ John Bolton The Risks and Weaknesses of the International Criminal Court from America's Perspective, (page 4) Law and Contemporary Problems. January 2001, while US ambassador to the United Nations

- ↑ J. Samuel, ({{{year}}}). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground," Diplomatic History, 29, 312.

- ↑ Walker, "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision", passim.

- ↑ Selden, Mark (2002-09-09). "Terrorism Before and After 9-11". Znet. http://www.zmag.org/content/showarticle.cfm?ItemID=2310. Retrieved 2008-01-30. </li>

- ↑ cuba and the us.p65

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Chomsky, Noam. Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance, Henry Holt and Company, 80.

- ↑ Sheldon M. Stern (2003). Averting 'the final failure': John F. Kennedy and the secret Cuban Missile Crisis meetings, Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Richard Kearney (1995). States of mind: dialogues with contemporary thinkers on the European mind, Manchester University Press.

- ↑ RodrÃguez, Javier The United States is an accomplice and protector of terrorism, states Alarcón. Granma. Archived from source 2007-06-09. URL accessed on 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Terrorism organized and directed by the CIA. Granma. Archived from source 2007-06-09. URL accessed on 2007-07-10.

- ↑ Landau, Saul Interview with Ricardo Alarcón. Transnational Institute. URL accessed on 2007-07-10. Template:Dead link

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations Report, Volume IV, page 125. September 22, 1978

- ↑ Wood, Nick Cuba's case against Washington. Workers World. URL accessed on 2007-07-10.

- ↑ "Cuba sues U.S. for billions, alleging 'war' damages". CNN. June 2, 1999. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20070310002911/http://edition.cnn.com/WORLD/americas/9906/02/cuba.billions/. Retrieved 2007-07-10. </li>

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Sanchez, Marcela (September 3, 2004). "Moral Misstep". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A57838-2004Sep2.html. </li>

- ↑ Investigator from Cuba takes stand in spy trial Miami Herald

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Cuba Statement to the United Nations 2001 since the Cuban revolution