Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Invasion of Grenada

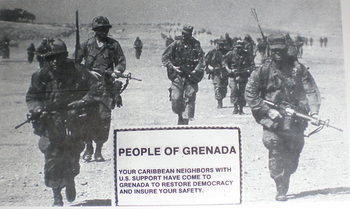

The Invasion of Grenada, codenamed Operation Urgent Fury (see Operation:IRONY), was a 1983 U.S.-led Wikipedia:invasion of Wikipedia:Grenada, that stopped any chance of the Wikipedia:People's Revolutionary Government revolutionary (WP) government from recovering from the death of its leader, Maurice Bishop (WP), and the coup that had overthrown it only weeks before.

As with all invasions, coups, wars and other sustained military actions against states after 1945 without international mandate for exception, it was illegal under the spirit of international law according to the precedent set by the Nuremberg trials Nuremberg Principles Principle VI (a) (i) : War of aggression.

The invasion was criticized by the United Kingdom, Canada (WP) and the United Nations General Assembly (WP), which condemned it as "a flagrant violation of international law (WP)".[1] Its multiple instances of attacks, bombardments, and armed violations of territory and the employment of armed forces to carry out acts of aggression were all violations of the International Criminal Court's statutes against crimes of aggression (WP) established in 2010, and were violations under the precedent set by the United Nations General Assembly (WP) Resolution 3314 (WP) of 1975 as acts of aggression.

The successful invasion led to a change of government but was controversial due to charges of American imperialism (WP), Cold War (WP) politics, the involvement of Cuba (WP), the unstable state of the Grenadian government, and Grenada's status as a Wikipedia:Commonwealth realm.

Grenada gained independence from the United Kingdom (WP) in 1974. Left wing rebels seized power in a coup in 1979. After four years of peaceful rule under revolutionary Prime Minister Maurice Bishop (WP), he was murdered in 1983. Only twelve days after Bishop's assassination, the invasion began on October 25, 1983, with the country's defenses crippled by the internal power struggle between his forces and those of Bernard Coard. A combined force of about 7,600 troops from the United States, Jamaica and members of the Regional Security System (RSS)[2] defeated Grenadian resistance and the Wikipedia:military government of Wikipedia:Hudson Austin was deposed.

Contents

[hide]Independence, Bishop government[edit]

Sir Wikipedia:Eric Gairy had led Wikipedia:Grenada to independence from the Wikipedia:United Kingdom in 1974. His term in office coincided with civil strife in Grenada. The political environment was highly charged and although Gairy – head of the Wikipedia:Grenada United Labour Party – claimed victory in the Wikipedia:general election of 1976, the opposition did not accept the result as legitimate. The civil strife took the form of street violence between government supporters and gangs organized by the Wikipedia:New Jewel Movement (NJM). In the late 1970s, the NJM began planning to depose the government. Party members began to receive military training outside of Grenada. On March 13, 1979 while Gairy was out of the country, the NJM – led by Wikipedia:Maurice Bishop – launched an armed revolution and overthrew the government, establishing the Wikipedia:People's Revolutionary Government. More than four years passed with no elections.

12 days of the Coard coup[edit]

On October 13, 1983, a party faction led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard seized power. Bishop was placed under house arrest. Mass protests against the action led to Bishop escaping detention and reasserting his authority as the head of the government. Bishop was eventually captured and murdered along with several government officials loyal to him. The army under Wikipedia:Hudson Austin then stepped in and formed a military council to rule the country. The Wikipedia:Governor-General of Grenada, Wikipedia:Paul Scoon, was placed under house arrest. The army announced a four-day total curfew where anyone seen on the streets would be subject to summary execution.

After the United States invaded, Cuba released a series of official documents to the press. According to these documents, when the murder of Maurice Bishop was reported on October 20, the Wikipedia:government of Cuba declared that it was "deeply embittered" by the murder and rendered "deep tribute" to the assassinated leader. The same official statement reported instructions to Cubans in Grenada that "they should abstain absolutely from any involvement in the internal affairs of the Party and of Grenada," while attempting to maintain the "technical and economic collaboration that could affect essential services and vital economic assistance for the Grenadian people."

On October 22, 1983, Fidel Castro (WP) sent a public message to "Cuban workers" in Grenada, stressing that they should take no action in the event of a U.S. invasion unless they were "directly attacked." If U.S. forces were to "land on the runway section near the university or on its surroundings to evacuate their citizens," Cubans were "to fully refrain from interfering."

Pretexts for intervention[edit]

The Wikipedia:Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), then chaired by Wikipedia:Eugenia Charles, the Prime Minister of Wikipedia:Dominica; as well as the nations of Wikipedia:Barbados, and Wikipedia:Jamaica appealed to the United States for assistance. According to a reporter for Wikipedia:The New York Times, this formal appeal was at the behest of the U.S. government, which had already decided to take military action.[3] U.S. officials cited the murder of Bishop and general political instability in a country near U.S. borders, as well as the presence of U.S. Wikipedia:medical students at Wikipedia:St. George's University on Grenada, as reasons for military action. Sivapalan also claimed that the latter reason was cited in order to gain public support.[4]

The US created plausible, if preposterous, deniability for not responding to Cuban efforts at diplomacy by claiming technical difficulties. On October 26, Wikipedia:Alma Guillermoprieto reported in Wikipedia:The Washington Post that at a "post-midnight news conference" with "almost 100 foreign and local journalists," Castro "released texts of what he said were diplomatic communications among Cuba, Grenada and the United States," giving the essential facts. U.S. sources "confirmed the exchange of messages," she added, but said they could not respond to Cuba at once because the telephone lines of the U.S. interest section in Havana were down from the evening of October 23 to late at night on October 24.

Wikipedia:Reagan administration spokesman, Wikipedia:Larry Speakes, said that "the U.S. disregarded Cuban and Grenadian assurances that U.S. citizens in Grenada would be safe because, 'it was a Wikipedia:floating craps game and we didn't know who was in charge'." The same issue was reported by Wikipedia:Alan Berger in Wikipedia:The Boston Globe on the same day.

Airport runway[edit]

The Bishop government constructed the Wikipedia:Point Salines International Airport with the help of Britain, Wikipedia:Cuba, Wikipedia:Libya, Wikipedia:Algeria, and other nations.

The airport had been first proposed by the British government in 1954, when Grenada was still a British colony. It had been designed by Canadians, underwritten by the British government, and partly built by a London firm. The Wikipedia:U.S. government accused Grenada of constructing facilities to aid a Soviet-Cuban military build-up in the Wikipedia:Caribbean, and to assist the Soviet and Cuban transportation of weapons to Wikipedia:Central American insurgents. Bishop’s government claimed that the airport was built to accommodate commercial aircraft carrying tourists, pointing out that such jets could not land at the existing airport on the island’s north. Neither could the existing airport, itself, be expanded as its runway abutted a mountain.

In 1983, then-Member of the Wikipedia:United States House of Representatives Wikipedia:Ron Dellums, traveled to Grenada on a fact-finding mission, having been invited by the country's Prime Minister. Dellums described his findings before Congress:

...based on my personal observations, discussion and analysis of the new international airport under construction in Grenada, it is my conclusion that this project is specifically now and has always been for the purpose of economic development and is not for military use.... It is my thought that it is absurd, patronizing and totally unwarranted for the United States Government to charge that this airport poses a military threat to the United States’ national security.[5]

In March 1983, Ronald Reagan began the propaganda campaign that would lead to invasion. He claimed "Soviet-Cuban militarization" posed a threat to the United States and the Caribbean. He said that the 9000 ft. runway and the oil storage tanks were unnecessary for commercial flights. He used the now-familiar lying technique of presenting imaginary evidence cloaked by military secrecy; "evidence from intelligence sources", the evidence not shown and the sources unnamed, showed that the airport was to become a Cuban-Soviet military airbase.[6]

Conclusion[edit]

The airport runway issue offers the clearest evidence that the 12-day coup was planned by the United States. It had been built up as a media issue by multiple sources nearly a year before the invasion. And it also shows a clear double standard: a US base with a dozen such runways could have been built without a single news story, let alone a media controversy.

The incompetent media and thusly ill-informed public never questioned how an airbase on a tiny island closer to South America than Cuba is to Florida could be the new and dangerous threat to America that would call for immediate action.

If the intelligence analysis hypothesis behind Reagan's lies were true, and commercial flights were only part of the economic reasons for building the long runway, then the fact that US bases dot the entire world like a pox should have been declared openly. Why should tiny nations that offer no great threat be the ones to answer for their actions, when the gigantic US, that is a constant threat, does not? When there is no evidence whatever that small nations, or even the former USSR, intend Wars of aggression, but the US has shown each and every single year since WWII that they plan to take over the world with their robot factory? Socialist and other marginalized nations must choose between adhering to the standard and lying, or flat out opposing it and risking reprisals. In this case, they would have been better served by telling the truth.

The invasion[edit]

The invasion, which commenced at 05:00 on October 25, 1983, was the first major operation conducted by the U.S. military since the Wikipedia:Vietnam War.

Wikipedia:Vice Admiral Wikipedia:Joseph Metcalf, III, Commander Second Fleet, was the overall commander of the U.S. forces, designated Joint Task Force 120, which included elements of each military service and multiple special operations units. Fighting continued for several days and the total number of U.S. troops reached some 7,000 along with 300 troops from the OECS. The invading forces encountered about 1,500 Grenadian soldiers and about 700 Wikipedia:Cubans.

The flag waving, ra-ra narrative offered by official U.S. sources states that the defenders were well-prepared, well-positioned and put up stubborn resistance, and yet US forces overwhelmed the Communist forces. The truth is that, as usual, coalition forces had total naval and air superiority, including helicopter gunships and naval gunfire support, and still the U.S. felt it necessary to call in two battalions of reinforcements on the evening of October 26. Opposition to US forces is never more of an impedence than a speedbump to a tank. That's really not the point, though, is it?

- Nearly eight thousand soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines had participated in URGENT FURY along with 353 Caribbean allies of the CPF. U.S. forces had sustained 19 killed and 116 wounded; Cuban forces sustained 25 killed, 59 wounded and 638 combatants captured. Grenadian forces casualties were 45 killed and 358 wounded; at least 24 civilians were killed.[7]

Reaction in the United States[edit]

After the hypocrisy of US "military advisors" in Viet Nam, much was made of the presence of 60 people from outside the Caribbean on the island, including Communist nations as far-flung as the Soviet Union, North Korea, East Germany, Bulgaria, and Libya. According to journalist Bob Woodward in his book "Veil", the supposed captured "military advisers" from the aforementioned countries were actually accredited diplomats and included their dependents. None took any actual part in the fighting.[8] Some of the "construction workers" were actually a detachment of Cuban Military Special Forces and combat engineers.[9]

A month after the invasion, Time magazine described it as having "broad popular support." A congressional study group concluded that the invasion had been justified, as most members felt that U.S. students at the university near a contested runway could have been taken hostage as U.S. diplomats in Iran had been four years previously. The group's report caused House Speaker Wikipedia:Tip O'Neill to change his position on the issue from opposition to support.[10]

However, some members of the study group dissented from its findings. Congressman Wikipedia:Louis Stokes stated: "Not a single American child nor single American national was in any way placed in danger or placed in a hostage situation prior to the invasion." The Wikipedia:Congressional Black Caucus denounced the invasion and seven Democratic congressmen, led by Wikipedia:Ted Weiss, "introduced a quixotic resolution to Wikipedia:impeach Reagan...which would, of course, go exactly nowhere."[10]

In the evening of October 25, 1983 by telephone, on the newscast Nightline, anchor Ted Koppel spoke to medical students on Grenada who stated that they were safe and did not feel their lives were in danger. The next evening, again by telephone, medical students told Koppel how grateful they were for the invasion and the Marines, which probably saved their lives. State department officials had assured the medical students that they would be able to complete their medical school education in the United States.[11][12]

International opposition and criticism[edit]

By a vote of 108 in favor to 9 (Wikipedia:Antigua and Barbuda, Wikipedia:Barbados, Wikipedia:Dominica, Wikipedia:El Salvador, Wikipedia:Israel, Wikipedia:Jamaica, Wikipedia:Saint Lucia, Wikipedia:Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada, and the United States voting against) with 27 abstentions, the Wikipedia:United Nations General Assembly adopted Wikipedia:General Assembly Resolution 38/7 which "deeply deplores the armed intervention in Grenada, which constitutes a flagrant violation of international law and of the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of that State".[1]

When asked if he was concerned by the lopsided 108-9 vote in the Wikipedia:UN General Assembly, then-president Ronald Reagan showed once again how fawning and inappropriate his nickname as the Great Communicator was, with the characteristically awkward and unimaginative non-sequitur "it didn't upset my breakfast at all" [13] see Great Conjob

The government of China termed the United States intervention an outright act of hegemonism (WP). The USSR government observed that Grenada had for a long time been the object of United States threats, that the invasion violated International law Wikipedia:international law, and that no small nation not to the liking of the United States would find itself safe if the aggression against Grenada was not rebuffed. The governments of some countries stated that the United States intervention was a return to the era of barbarism. The governments of other countries said the United States by its invasion had violated several treaties and conventions to which it was a party.[14]

A similar resolution was discussed in the Wikipedia:United Nations Security Council and although receiving widespread support it was ultimately vetoed by the United States.[15][16]

Grenada is part of the Wikipedia:Commonwealth of Nations and, following the invasion, it requested help from other Commonwealth members. The invasion was opposed by the Wikipedia:United Kingdom, Wikipedia:Trinidad and Tobago, and Wikipedia:Canada, among others.[17] British Prime Minister Wikipedia:Margaret Thatcher personally opposed the U.S. invasion, and her Wikipedia:Foreign Secretary, Wikipedia:Geoffrey Howe, announced to the Wikipedia:British House of Commons on the day before the invasion that he had no knowledge of any possible U.S. intervention. Wikipedia:Ronald Reagan, Wikipedia:President of the United States, assured Thatcher that an invasion was not contemplated. Reagan later said, "She was very adamant and continued to insist that we cancel our landings on Grenada. I couldn't tell her that it had already begun."[18]

After the invasion, Prime Minister Thatcher wrote to President Reagan: This action will be seen as intervention by a Western country in the internal affairs of a small independent nation, however unattractive its regime. I ask you to consider this in the context of our wider East-West relations and of the fact that we will be having in the next few days to present to our Parliament and people the siting of Wikipedia:Cruise missiles in this country...I cannot conceal that I am deeply disturbed by your latest communication.[19][20] The full text remains classified.

Where military action in Central America had been declared by Ronald Reagan justified as a clear case of "Communist aggression in our own backyard",[21] Grenada is a harder sell; it is closer to South America than Florida is to Cuba. Reagan was using a phrase used by Republicans and other US nationalists to justify unilateral military action against other governments, specifically Guatemala in 1954, and a concept of paternal authority over world affairs that went back to Theodore Roosevelt and even into the 19th century.[21] Moreover, while Cuba was content to deal with either government, and there seemed little difference between them, the one distinguishing feature of the new one was that it was new and weak, and therefore the US action (and the collaboration of the Caribbean states) against the second coup government and not the first, gratuitous.

The timing of the invasion was not inconsistent with the average of two years between each CIA coup during the years the CIA has been in operation; 30 in all. It is quite possible that all the coups were planned in this way, with a lack of support from the Grenada islanders and a great deal of support from the Caribbean being the only reasons that this invasion was overt and the others were covert.

Aftermath[edit]

Following the U.S. victory, Grenada's Governor-General Wikipedia:Paul Scoon formed a government.[10] U.S. forces remained in Grenada after combat operations finished in December. Elements remaining included military police, special forces, and a specialized intelligence detachment. Previous statement uncited and of dubious origin-an IP address that only ever made 2 edits, with a ref name that corresponds to no author on the subject in Google Books: Sundin

The invasion showed problems with the U.S. government's "information apparatus," which Time described as still being in "some disarray" three weeks after the invasion.[10] For example, the U.S. State Department falsely claimed that a Wikipedia:mass grave had been discovered that held 100 bodies of islanders who had been killed by Communist forces.[10] Major General Wikipedia:Norman Schwarzkopf, deputy commander of the invasion force, said that 160 Grenadian soldiers and 71 Cubans had been killed during the invasion; Wikipedia:the Pentagon had given a much lower count of 59 Cuban and Grenadian deaths.[10] Ronald H. Cole's report for the Joint Chiefs of Staff showed an even lower count.[7]

Also of concern were the problems that the invasion showed with the military. There was a lack of intelligence about Grenada, which exacerbated the difficulties faced by the quickly assembled invasion force.[10] For example, it was not known that the students were actually at two different campuses and there was a thirty-hour delay in reaching students at the second campus.[10] Maps provided to soldiers on the ground were rudimentary, did not show Wikipedia:topography, and were not marked with crucial positions. The Wikipedia:U.S. Navy ships providing naval gunfire and U.S. Marine and Navy fighter bomber support, as well as Wikipedia:U.S. Air Force aircraft providing close air support mistakenly fired upon and killed U.S. ground forces due to differences in maps and location coordinates, datum, and methods of calling for fire support.[22] The landing strip was drawn-in by hand on the map given to some members of the invasion force.

The precipitousness of the invasion had contributed to opposition against it; no one saw it coming.[23] Its speed, though, ended up stifling dissent: media coverage was too brief for the issue to gain momentum.[10] The US was able to find interests in Grenada who viewed the post-coup regime as illegitimate.[24]

On 29 May 2009, the Wikipedia:Point Salines International Airport was officially renamed in honour of the slain pre-coup leader Maurice Bishop by the Government of Grenada.[25][26]

There are no citations to support it, even local Grenadian ones, but one might suppose that at the very least, US flag wavers in Grenada might celebrate October 25 as a national holiday, and call it Thanksgiving Day.

Goldwater-Nichols Act[edit]

Wikipedia has it that "...Analysis by the U.S. Department of Defense showed a need..." which in the Act. Firstly, there is never a paramount "need" in any civilized society for any military functions whatever. Only the implementation of more important considerations can justify it, such as when the continued peaceful existence of humanity is existentially threatened by the existence of nations that believe in force. But secondly, there is no evidence presented in Wikipedia:Invasion of Grenada#Goldwater-Nichols Act that there was any connection between DoD reports and the Act, other than dates

Other[edit]

Wikipedia:St. George's University built a monument on its True Blue campus to memorialize the US servicemen killed during the invasion, and marks the day with an annual memorial ceremony.In 2008, the Wikipedia:Government of Grenada announced a move to build a monument to honour the Cubans killed during the invasion. At the time of the announcement the Cuban and Grenadian government are still seeking to locate a suitable site for the monument.[27]

A heavily fictionalized account of the invasion from a U.S. military perspective is shown in the 1986 Wikipedia:Clint Eastwood movie, Wikipedia:Heartbreak Ridge.

Order of battle[edit]

U.S. land forces[edit]

- 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit

- 82nd Airborne Division - large contingent

- 27th Engineer Battalion

- Wikipedia:21st Tactical Air Support Squadron - jump qualified FACs deployed with 82nd Airborne

- U.S. Air National Guard - provided A-7D Corsair II Wikipedia:ground-attack aircraft for Wikipedia:close air support

- 437th Military Airlift Wing - provided airlift support with Wikipedia:C-141 Starlifters

- Wikipedia:16th Special Operations Wing - flew AC-130H Spectre gunships

- 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing - provided air superiority cover for allied forces with Wikipedia:F-15 Eagles

- Wikipedia:75th Ranger Regiment - 1st and 2nd Battalions

- Navy SEALs: SEAL Team FOUR and SEAL Team SIX

- 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta

- E co 3/60th Inf Reg (later designated: E co Wikipedia:109th MI Battalion 9th ID LRSC (1984)

- 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne)

- Wikipedia:5th Weather Squadron, 5th Weather Wing (MAC) - Jump qualified Combat Weathermen who deployed with the 82nd

- Wikipedia:317th Military Airlift Wing - provided airlift support with Lockheed C-130 Hercules (Pope AFB NC)

[edit]

Amphibious Squadron Four Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS

Independence Task Group Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS with the Invasion Tactical Planning and Hands On Operational Control conducted by the Air Staff of the USS Independence

In addition, the following ships supported naval operations: Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, Template:USS, and Template:USCGC

Wikipedia:Caribbean Peace Force (CPF)

Notes[edit]

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Invasion of Grenada on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 United Nations General Assembly resolution 38/7, page 19. United Nations.

- Jump up ↑ Country-data.com -- Caribbean Islands: A Regional Security System

- Jump up ↑ New York Times, Mythu Sivapalan, October 29, 1983

- Jump up ↑ Cole, op. cit., p.1, 57

- Jump up ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified Peter Collier, Wikipedia:David Horowitz. Commentary.

- Jump up ↑ Gailey, Phil; Warren Weaver Jr. Grenada. New York Times. URL accessed on accessdate=2008-03-11.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Ronald H. Cole, 1997, Operation Urgent Fury: The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada 12 October - 2 November 1983 Joint History Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Washington, DC, p.62.] (Retrieved November 9, 2006).

- Jump up ↑ Woodward, Bob (1987). Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA 1981-1987, Simon & Schuster.

- Jump up ↑ Leckie, Robert (1998). The Wars of America, Castle Books.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Magnuson, Ed Getting Back to Normal.

- Jump up ↑ http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=656934

- Jump up ↑ http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/diglib-fulldisplay.pl?SID=20100809760314941&code=tvn&RC=656937&Row=341

- Jump up ↑ The Spokesman-Reviev, 101st year, no. 170, 4 November 1983, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1314&dat=19831104&id=uDcSAAAAIBAJ&sjid=6O4DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5592,2048008

- Jump up ↑ United Nations Yearbook, Volume 37, 1983, Department of Public Information, United Nations, New York

- Jump up ↑ Zunes, Stephen (October 2003). The U.S. Invasion of Grenada: A Twenty Year Retrospective, Foreign Policy in Focus.

- Jump up ↑ Spartacus Educational.

- Jump up ↑ Cole, op. cit., p. 50

- Jump up ↑ Reagan, Ronald (1990). An American Life page 454.

- Jump up ↑ Thatcher letter to Reagan ("deeply disturbed" at U.S. plans) [memoirs extract]. Margaret Thatcher Foundation. URL accessed on 2008-10-30.

- Jump up ↑ Thatcher, Margaret (1993) The Downing Street Years page 331.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Cuba in the American imagination: metaphor and the imperial ethos By Louis A. Pérez "

- Jump up ↑ Friendly Fire Google Search

- Jump up ↑ Cole, op. cit., p. 50

- Jump up ↑ Wikipedia:Steven F. Hayward. The Age of Reagan: The Conservative Counterrevolution: 1980-1989, Crown Forum.

- Jump up ↑ St Vincent PM to officiate at renaming of Grenada international airport. Caribbean Net News newspaper.

- Jump up ↑ BISHOP'S HONOUR: Grenada airport renamed after ex-PM. Wikipedia:Caribbean News Agency (CANA).

- Jump up ↑ For Cubans - "The Nation Newspaper", 13 October 2008

USS KIDD DDG-993 was relieved by the two PHMS 3 & 4 not sure why Kidd keeps getting cut out. - No one cares about your little 'Kilroy was here' graffiti, that's why

Further reading[edit]

- Stewart, Richard W.. Operation Urgent Fury: The Invasion of Grenada, October 1983, Wikipedia:United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70–114–1.

- Cole, Ronald H. (1997). Operation Urgent Fury:The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada, 12 October - 2 November 1983.

External links[edit]

- Operation: Urgent Fury, Grenada

- The 1983 Invasion of Grenada, Operation: Urgent Fury

- A history of the operation from the U.S. perspective as written by naval historians.

- Grenada - a 1984 comic book about the invasion written by the CIA.

- NBC Nightly News report on day of Invasion of Grenada

Template:Cold War Template:American conflicts Template:Cuban conflictssimple:1983 Invasion of Grenada

- Anarchopedia

- Anarchopedia essays

- Caribbean – United States relations

- Cuba – United States relations

- Conflicts in 1983

- 1983 in the United States

- 1983 in Grenada

- Act of aggression

- Crime of aggression

- History of Grenada

- History of the United States

- Invasions after 1945

- Invasions after 1975

- Invasions by the United States

- Military expeditions of the United States

- Operations involving American special forces

- Reagan administration controversies

- United States Army Rangers

- United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

- War of aggression

- Wars involving Antigua and Barbuda

- Wars involving Barbados

- Wars involving Cuba

- Wars involving Dominica

- Wars involving Grenada

- Wars involving Jamaica

- Wars involving Saint Lucia

- Wars involving Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Wars involving the United States