Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Greater Albania

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Greater_Albania on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |

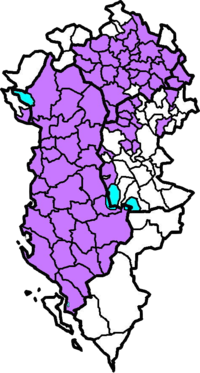

The term Greater Albania or Great Albania refers to land which is outside the borders of the Republic of Albania that Albanian nationalists claim as their own, because of either present-day or historical presence of Albanian populations in those areas. The term implies a desire for territorial expansion. Albanians themselves mostly use the term ethnic Albania instead.

Contents

[hide]Albanians under Ottoman Turkey[edit]

Prior to the Balkan wars of the beginning of the 20th century, Albanians were subjects of the Ottoman Empire.

The Albanian independence movement emerged in 1878 with the League of Prizren (a council based in Kosovo) whose goal was cultural and political autonomy for ethnic Albanians inside the framework of the Ottoman Empire. However, the Ottomans were not prepared to grant The League's demands. Ottoman opposition to the League's cultural goals eventually helped transform it into an Albanian national movement.

Ethnic Albania[edit]

Ethnic Albania is a term used primarily by Albanian nationalists to denote the territories claimed as the traditional homeland of the ethnic Albanians. These territories include Albania, Kosovo, and parts of Republic of Macedonia (with some referring to as Ilirida) and Montenegro (Malësia, Ulcinj, etc.). Parts of the Epirus region of Greece referred to by Albanians as Çamëria are also sometimes included in this definition.

World War II[edit]

During World War II, with the fall of Yugoslavia in 1941, Italians placed the land inhabited by ethnic Albanians under the jurisdiction of an Albanian quisling government. That included Kosovo, parts of Macedonia and Montenegro.

Current status[edit]

The current status talks on the future of Kosovo (and possible independence) could be interpreted as a degree of success in the creation of a Greater Albania (were such territory to be annexed to Albania or federated with the state), although the United Nations (UN) has stated that if as a result Kosovo becomes independent, annexation to another state would not be possible. In a survey carried out by United Nations Development Programme, UNDP, and published in March 2007 only 2.5% of the Albanians in Kosovo think unification with Albania is the best solution for Kosovo. 96% say they want Kosovo to become independent within present borders.[1]

Territories claimed[edit]

Kosovo[edit]

Kosovo presently has an overwhelmingly Albanian majority, estimated to be around 90%.[unverified]

Montenegro[edit]

Montenegro also contains sizeable Albanian populations mostly concentrated in areas such as southern Malësia, the Ulcinj (Ulqini) municipality on the coast, the Tuzi area near Podgorica, and parts of the Plav (Plava), Gusinje (Guci) and Rožaje (Rozhajë) municipalities.[unverified]

Southern Epirus (Çamëria)[edit]

Southern Epirus was part of the newly-formed Albanian state that proclaimed independence on November 28, 1912 but it was annexed to Greece following the London Conference of 1913. After the capitulation of Italy in 1943, some of the Çams joined forces with the German occupation army, forming a special Çam unit. Other members of the Çams community (300-500) joined the National Liberation Front (EAM). EAM had about 2,500,000 members in 1944. After the war, many of the Albanians in Epirus were forced to leave Greece by EDES (an extreme right-wing Greek nationalist partisan organization) in 1944. According to the 1928 census held by the Greek state, there were 18,600-19,600 Muslim Cams in southern Epirus.In the first post-war census (1951), only 123 Muslim Çams were left in the area. Descendants of the exiled Muslim Çams (up to 200,000 living in Albania) claim that up to 35,000 Muslim Çams were living in southern Epirus before World War II. They call themselves Çam (Cham) after the Albanian word for Epirus, Çamëria but also the term Epir is used alone. Many of them are currently trying to pursue legal ways to claim compensation for the properties seized by Greece. Nowadays, only immigrant Albanians live in the area as a result of the fall of the communist regime in Albania in the late 1980s[2] but this strongly opposed by other independent sources and all the ethnic Albanians, arguing that Christian ethnic Albanian remained in the area .[3]

Republic of Macedonia[edit]

The western part of the Republic of Macedonia is an area with a large ethnic Albanian minority. The Albanian population in Macedonia is variously estimated to make up between 23%-25% of the population. Cities with Albanian majorities or large minorities include Tetovo (Tetova), Gostivar (Gostivari), Struga (Struga), Debar (Diber), Kumanovo (Kumanova) and Skopje (Shkup).[unverified]

Preševo Valley[edit]

The municipalities of Preševo (Presheva), Bujanovac (Bujanovci) and part of the municipality of Medveđa (Medvegja) also contain Albanian populations. According to the 2002 census, Preševo contained an overwhelming Albanian ethnic majority of over 90%. Bujanovcac around 54.69% and Medveđa 48.17%. Tense relations between ethnic Serbians and Albanians and also the increased hatred after the Kosovo War, resulted in military actions after the Liberation Army of Preševo, Medveđa and Bujanovac (UÇPMB) was formed. One of UÇPMB's roles entails seceding these specific municipalities from Yugoslavia and annex them to a future independent Kosovo.[unverified]

Political uses of the concept[edit]

The Albanian problem in the Balkan peninsula is in part the consequence of the decisions made by Western Powers. One theory posits that the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Austro-Hungary wanted to maintain a brittle balance in Europe in the late 19th century following the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

| “ | We spent the 1990s worrying about a Greater Serbia. That's finished. We are going to spend time well into the next century worrying about a Greater Albania. | †|

| —Christopher R. Hill, US Ambassador to F.Y.R.O.M., 1999[4]

International Crisis Group Research[edit]International Crisis Group researched the issue of Pan-Albanianism and published a report titled "Pan-Albanianism: How Big a Threat to Balkan Stability?" on February 2004. Their report concludes that the "notions of pan-Albanianism are far more layered and complex than the usual broad brush characterisations of ethnic Albanians simply bent on achieving a greater Albania or a greater Kosovo." Furthermore, the report states that amongst Albanians "violence in the cause of a greater Albania, or of any shift of borders, is neither politically popular nor morally justified." International Crisis Group advises the Albanian and Greek governments to endeavour and settle the long-standing issue of the Chams displaced from Greece in 1945, before it gets hijacked and exploited by extreme nationalists, and the Chams' legitimate grievances get lost in the struggle to further other national causes. Moreover, the ICG findings suggest that Albania is more interested in developing cultural and economic ties with Kosovo, whilst maintaining separate statehood.[5] See also[edit]

External links[edit]

References[edit]

Sources[edit]

|

||