Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Economic constraints on media freedom

Media freedom is constrained by the economic system when market interests of media enterprises dominate the public function of media. Media freedom is restricted by the economic system in terms of media independence and media diversity. Research on this topic has been done by media politics and media economics.

| This article contains content from Wikipedia An article on this subject has been nominated for deletion on Wikipedia: Wikipedia:Articles for deletion/ Economic Constraints on Media Freedom Current versions of the GNU FDL article on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article |

WP+ NO DEL |

- Media Independence

Media independence is challenged by the economic system when economic pressure groups control the production of independent media outlets. To fulfill their democratic function, media have to provide information, which are neither solely driven by profit nor by the opinion of few powerful parties[1].

- Media Diversity (also: Media Pluralism or Media Plurality)

Media diversity is endangered when the market-orientation of media negatively affects the plurality of media outcomes. Media diversity is divided into different sub dimensions: plurality of ownership, viewpoints and sources of information/channels[1][2]. Free media as public goods maintain and support democratisation, as they provide diverse information for the citizens, so that they may take an active role in democracy (WP). Free media, which reflect diverse viewpoints, also serve as mediators between different social groups[1].

As public goods, media have to provide independent and diverse information for the citizens, so that they may participate in the democratic process. However, Media do not only serve as public cultural goods, but also as economic commodities[2][3]. From an economic point of view, media systems have to perform well and be efficient. Since the expensive production of public goods often contradicts economic efficiency, they tend to be systematically under-produced in the market[4]. The scholar Just states a value conflict between public and economic interests[5].

Contents

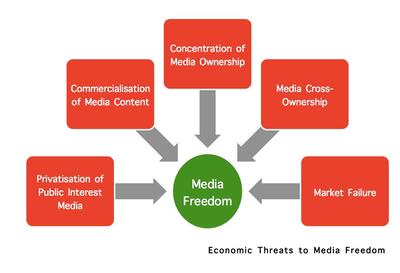

[hide]Economic Threats to Media Freedom

Economic threats to media freedom are market failure, concentration of media ownership, media cross-ownership, privatisation of public interest media and commercialisation of media content, which have been stated by the scientific community.[6][2]

In the last decades, several scholars have stated a change of regime between the two functional systems: the public and the economic system [7]. In other words, an increasing commercialisation of the media has been noted in the United States and in Europe[8]. This liberalisation has had multiple effects on the media systems, such as striking media concentration and Wikipedia:media cross-ownership in the United States and in Europe. There have also been recent attempts to privatise public television in Europe, for example in Wikipedia:Poland[9]. These developments have been highly criticized by international scientists as economic threats to media freedom and democracy[1][10]. Governments also may use economic pressure to control the development of national media markets and media content. This is the case in many former communist countries such as Wikipedia:Russia and Wikipedia:Bulgaria[11].

Due to the fact that public goods tend to be systematically under-produced in the market[12], market failure is striking in deregulated media markets. As a consequence of market failure, monopoly practices, mergers and concentration of media ownership present huge threads to media freedom in terms of diversity. In a country, where few companies control the entire media in one sector or even across different media sectors (print, broadcasting, telecommunications), diversity is affected in all dimensions mentioned above.

Consequences of Liberalisation and Privatisation of Media Markets

The privatisation and the liberalisation of television that began in the final decades of the 20th century in the United States (WP) and in Europe (WP), resulted not only in an increasing commercialisation of media content but also in an increasing concentration of media ownership.

While more private channels have been beneficial for external pluralism of television, a greater dependence on advertising has had negative effects on its freedom from economic pressure. A liberalisation process has not only been reported for broadcasting but also for news media in general. The increasing market-orientation of European and American news media had been responsible for cutting back editorial staff even before the digital revolution began[13].

Recently, concentration of media ownership has become one of the major threats to media freedom within the European Union (WP), and in the United States. The problem of media concentration is not only related to the stronger market orientation of broadcasting and print media, but also to the expansion of the hardly regulated telecommunications sector[2]. Wikipedia:Media convergence as a consequence of the rise of new communication technologies has caused concentration of media ownership, too.[10]

Consequences of the Digital Revolution

With the digital revolution (WP) in the final years of the 20th century, print media enterprises have especially been facing a new crisis, since the economic condition and economic independence of the press have been injured. According to Starr, despite the positive consequences of the Internet for freedom of expression and freedom of information, the success of new media has had ambiguous effects on media freedom: […] the digital revolution has both revitalized and weakened freedom of the press. It has revitalized journalism by allowing new entrants into the media and generated promising innovations [...] but [...] in the established democracies, the digital revolution has weakened the ability of the press to act as an effective agent of public accountability [...] [14]

The economic base for media enterprises has been undermined by the fact, that the access for the public to find media content and for advertisers to reach consumers is no longer limited with the rise of digital media.[13] As a result, audiences have been shrinking and advertisers have tended to use new advertising platforms on the Internet instead of sponsoring news media. Since media enterprises are having problems with financing the production of original news stories and information, professional employment in journalism has dramatically declined.[13]

These developments dramatically endanger the production of free and diverse journalistic contents: [...] economic pressures will likely undermine their capacity for original reporting of the news [...] and with fewer resources and less influence over public opinion, they will be less capable of standing up to powerful interests in both the state and private sector[15].

Media Regulation and Media Freedom

Media regulation generally refers to […] laws and guidelines that influence the way media companies produce, distribute or exhibit materials for audiences. Regulatory bodies do not only act on national, but also on international levels like the European Commission. Regulation can further be divided into government regulation, self-regulation (by media companies) and co- regulation (by government and media companies)[16].

In the broadest terms, two different viewpoints on media regulation can be distinguished: according to supporters of liberal media systems, only deregulation enables an independent development of media.[10] In the tradition of a free market place of ideas, media freedom is guaranteed by external pluralism. In contrast, supporters of the social responsibility or social democratic model argue that media freedom requires regulation in order to ensure internal pluralism and participation.[10]

There are different Wikipedia:Concepts of Media Freedom behind these different viewpoints on regulation. They can be generally categorised in negative and positive media freedom concepts: media freedom in a negative sense implicates freedom from regulation, while media freedom understood in a positive way is in favour of certain regulation measures in order to guarantee freedom to diverse viewpoints

Regulation of Media Markets in Europe and the US

In practice, despite global Wikipedia:privatisation and Wikipedia:liberalisation tendencies, media and especially broadcasting markets are much more regulated in Wikipedia:Europe than in the Wikipedia:United States. In an often-cited framework Wikipedia:Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics, Hallin and Mancini (2004) categorise 18 Western Wikipedia:democracies into three media system models by distinguishing – among others – different state regulation policies (Role of the State in Media System)[17]: While the media system of the United States, which is typically subsumed under the North Atlantic or Liberal Model, is hardly regulated by politics, Southern European, Central and North European media systems, which are subsumed under the Polarized Pluralist Model (e.g. Wikipedia:Greece) and the Democratic Corporatist Model (e.g. Scandinavian countries), are characterised by a strong state intervention.

There are differences between state intervention in the Polarized Pluralist and the Democratic Corporatist Model of media systems:[17] In the Southern European Wikipedia:democracies, the role of the state as an owner, regulator, and funder of media has been historically important, though a fast and strong Wikipedia:commercialisation of broadcasting has been stated recently. In the Northern and Central European media system, a strong Wikipedia:liberal tradition of press freedom and a relatively strong state support for and regulation of media exist in parallel.

Press subsidies exist in some European countries like France, Italy and the Scandinavian states, such as Norway and Finland. Subsidies of the printed press may inhibit ownership concentration in the print media sector, in order to promote press freedom. In Finland, which is the closest real type to Hallin and Mancinis Democratic Corporatist Model, a mixture of public press Wikipedia:subsidies has existed since the 1970’s. The state press Wikipedia:subsidies address print media, cultural and opinion papers, and the party press. Furthermore, both the party press and regional and national newspapers may receive government subventions[18]. The current economic crisis indicates, that the deregulated American news media are suffering more from the financial problems than relatively strongly regulated North-European news media, which do not depend as much as American media enterprises on advertising revenues.[13]

Czepek, et. al describe different Wikipedia:pan-European economic structures, which implicate different conditions for Wikipedia:media freedom and diversity.[10] They show, that Wikipedia:media freedom in Wikipedia:Europe is influenced by specific media system clusters (strong public service broadcasting systems, public television, small media markets, trans-national media investments) and by Wikipedia:pan-European developments (regulation/deregulation of media markets, Wikipedia:media concentration, Wikipedia:commercialisation, declining resources for journalistic work).

| Pan-European development[19] | Media System Cluster |

|---|---|

| Regulated broadcasting market; deregulated print media market | Strong public service broadcasting systems with regulation regarding content diversity in co-existence with commercial broadcasting (dual systems) (Austria (WP), Finland (WP), Germany (WP), United Kingdom (WP)) |

| Concentration of media ownership | Public television system controlled or strongly influenced by governments in co-existence with commercial broadcasting (Bulgaria (WP), France (WP), Italy (WP), Poland (WP), Poland (WP), Spain (WP)) |

| Increasing dominance of commercial goals | Small market characteristics (Austria, Finland, Lithuania (WP)) |

| Declining resources for journalistic work | Trans-national media investments (Austria, Bulgaria, Wikipedia:Poland, Romania)

Fragmented media markets (Romania, Bulgaria) |

Most of the existing media regulations in the United States and in Europe concern the increasing concentration of media ownership. This has been criticised by scholars: […] an ideal policy will be concerned with more issues than mere ownership concentration. Rules structuring control of decision-making within media entities respond to the same value-based concerns. Which groups of people or which individuals, with relations to various wider societal groups, should exercise control is also important[20].

Regulatory bodies may legally prohibit mergers of big media enterprises in order to inhibit Wikipedia:concentration of media ownership. In 2006, this was the case in Germany, when KEK, an independent competition authority, reported crucial negative consequences if the biggest German print media concern Axel Springer merged the German Broadcasting enterprise Wikipedia:ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG[21]. Not only is Axel Springer Media AG the second biggest media company in Germany, but also, Axel Springer together with Wikipedia:Bertelsmann AG control major parts of the German print media sector. The German broadcasting sector is mainly dominated by two enterprises: ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG and Wikipedia:RTL Group. The German Commission on Concentration in the Media (KEK), which is the regulatory body responsible for ensuring a diversity of opinions in German broadcasting, argued, that Axel Springer Media AG would reach a 30 per cent of audience share by taking over ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG and as a consequence, would present a threat to media freedom in terms of diversity.[2]

See also

- Wikipedia:Bertelsmann

- Wikipedia:Commercialisation

- Wikipedia:Concepts of Media Freedom

- Wikipedia:Concentration of media ownership

- Wikipedia:Democracy

- Wikipedia:Economies of Scale

- Wikipedia:Economic efficiency

- Wikipedia:Market Failure

- Wikipedia:Citizens' perspective on media freedom

- Wikipedia:Media Sustainability Index (MSI)

- Wikipedia:Media cross-ownership in the United States

- Wikipedia:News Media

- Wikipedia:Policy

- Wikipedia:Public Broadcast

- Wikipedia:ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG

- Wikipedia:RTL Group

- Wikipedia:Subsidy

Footnotes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Baker, 2007

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Just, 2009

- Jump up ↑ Just, 2009; Kiefer, 2005

- Jump up ↑ Starr, 2012, p.238

- Jump up ↑ Just, 2009, p.139

- Jump up ↑ Puppis, ; Kiefer, 2005; Baker,2007; Just,2009

- Jump up ↑ Kiefer, 2005

- Jump up ↑ Baker, 2002; Kiefer, 2005

- Jump up ↑ Czepek, Hellwig, & Nowak, 2009

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Czepek, et al., 2009

- Jump up ↑ Kopper, 1993

- Jump up ↑ Starr, 2012, p.238

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Starr, 2012

- Jump up ↑ Starr, 2012, p.235

- Jump up ↑ Starr, 2012, p.240

- Jump up ↑ Tarow, 2009, p.82

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Hallin, & Mancini, 2004

- Jump up ↑ Salovaara-Moring, 2009

- Jump up ↑ Czepek, et al., 2009, p.13

- Jump up ↑ Baker, 2002, p.130

- Jump up ↑ Rosenbach, 2006

References

- Baker, C.E. (2007). Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. New York: Cambridge University.

- Baker, C.E. (2002). Media Concentration: Giving up on Democracy. In Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series (16).

- Baker, C.E. (1994). Advertising and a democratic Press. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Czepek, A., Hellwig, M., & Nowak, E. (2009). Introduction: Structural Inhibition of Media Freedom and Plurality across Europe. In Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Just, Natascha (2009). Measuring media concentration and diversity: new approaches and instruments in Europe and the US In Media, Culture & Society, 31(1), 97-117. doi: 10.1177/0163443708098248

- Kiefer, M. (2005). Medienökonomik. München: Oldenburg.

- Kopper, G. (1993). On the Methodological Problems of New Ideas and Approaches to Press Concentration Research. Journal Of Media Economics, 6(1), 25-35.

- Rolland, A. (2008). The Norwegian media ownership act and the freedom of expression In 'International Journal Of Media & Cultural Politics, 4(3), 313-330. doi: 10.1386/macp.4.3.313_1

- Rosenbach, M. (2006). Ab nach Acapulco. In: Der Spiegel, 6(2006), (82).

- Shiner, R. A., & Weaver, S. (2008). Review Essay: Media Concentration, Freedom of Expression, and Democracy. Canadian Journal Of Communication, 33(3), 545-549.

- Starr, P. (2012). An Unexpected Crisis: The News Media in Postindustrial Democracies. International Journal Of Press/Politics, 17(2), 234-242. doi:10.1177/1940161211434422

- Salovaara-Moring, I. (2009). Mind the Gap?: Press Freedom and Pluralism in Finland In Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Saura, L. (2010). Economic, Political and Communicative power in the neoliberal societies. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 13(65), 1-10. doi:10.4185/RLCS-65-2010-897-244-254-EN

- Tarow, J. (2009).Media Today: An introduction to mass communications. New York: Routledge

- Tracy, J. (2008). Review: C. Edwin Baker, Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. £35.00 (hbk), £14.99 (pbk). 256 pp In European Journal of Communication, 23(249), 249-253. doi: 10.1177/02673231080230020610