Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Difference between revisions of "Dark Satanic Mills"

Anarchangel (Talk | contribs) (Wikipedia Start) |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 12:13, 23 May 2012

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article And did those feet in ancient time on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |

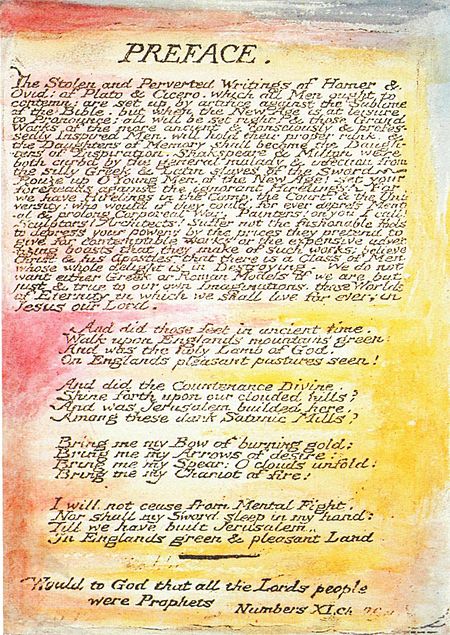

"And did those feet in ancient time" is a short poem by William Blake William Blake from the preface to his epic Wikipedia:Milton a Poem, one of a collection of writings known as the Prophetic Books. The date on the title page of 1804 for Milton is probably when the plates were begun, but the poem was printed c. 1808.[1] The term "dark Satanic Mills" came into common use in the English language from this poem. Today the poem is best known as the Wikipedia:anthem "Jerusalem", with music written by Sir Wikipedia:Hubert Parry in 1916.

The original text is found on the preface Blake printed for inclusion with Milton, a Poem, following the lines beginning "The Stolen and Perverted Writings of Homer & Ovid: of Plato & Cicero, which all Men ought to contemn: ..."[2]

Blake's poem

- And did those feet in ancient time. / Walk upon England's mountains green: / And was the holy Lamb of God, / On England's pleasant pastures seen!

- And did the Countenance Divine, / Shine forth upon our clouded hills? / And was Jerusalem builded here, / Among these dark Satanic Mills?

- Bring me my Bow of burning gold; / Bring me my Arrows of desire: / Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold! / Bring me my Chariot of fire!

- I will not cease from Mental Fight, / Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand: / Till we have built Jerusalem, / In England's green & pleasant Land

Beneath the poem Blake inscribed an excerpt from the Bible: "Would to God that all the Lord's people were Prophets" Numbers XI.Ch 29.v.[2] (Wikipedia:Book of Numbers 11:29).[3]

Contents

"Dark Satanic Mills"[edit]

thumb|Albion Flour Mills. The term "dark Satanic Mills", which entered the English language from this poem, is often interpreted as referring to the early Wikipedia:Industrial Revolution and its destruction of nature and human relationships.[4] This view has been linked to the fate of the Albion Flour Mills, which was the first major factory in London, designed by John Rennie and Wikipedia:Samuel Wyatt and built on land purchased by Wyatt in Wikipedia:Southwark. This was a rotary steam-powered flour mill by Wikipedia:Matthew Boulton and James Watt, with grinding gears by Rennie,[5] producing 6,000 Wikipedia:bushels of flour a week. The factory could have driven independent traditional millers out of business, but it was destroyed in 1791 by fire, perhaps deliberately. London's independent millers celebrated with placards reading, "Success to the mills of ALBION but no Albion Mills."[6] Opponents referred to the factory as Wikipedia:satanic, and accused its owners of adulterating flour and using cheap imports at the expense of British producers. An illustration of the fire published at the time shows a Wikipedia:devil squatting on the building.[7] The mills were a short distance from Blake's home.

Blake's phrase resonates with a wider theme in his works, what he envisioned as a physically and spiritually repressive ideology based on a quantifiable reality. Blake saw the Wikipedia:cotton mills and Wikipedia:collieries of the period as a mechanism for the enslavement of millions, but the concepts underpinning the works had a wider application:[8][9]

"And all the Arts of Life they changed into the Arts of Death in Albion./...[10] "

Another interpretation, amongst Wikipedia:Non-Conformists, is that the phrase refers to the established Wikipedia:Church of England. As a part of the establishment, the Church preached a doctrine of conforming to the social order, in contrast to Blake. In 2007 the new Bishop of Wikipedia:Durham, Wikipedia:N. T. Wright, explicitly recognised this element of English subculture when he acknowledged this alternative view that the "dark satanic mills" refer to the "great churches".[11]

thumb|300px|The first reference to Satan's "mills", next to images of megaliths An alternative theory is that Blake is referring to a mystical concept within his own mythology related to the ancient history of England. Satan's "mills" are referred to repeatedly in the main poem, and are first described in words which suggest neither industrialism nor ancient megaliths, but rather something more abstract: "the starry Mills of Satan/ Are built beneath the earth and waters of the Mundane Shell...To Mortals thy Mills seem everything, and the Harrow of Shaddai / A scheme of human conduct invisible and incomprehensible".[12]

Wikipedia:Stonehenge and other megaliths are featured in Milton, suggesting they may relate to the oppressive power of priestcraft in general; as Peter Porter observed, many scholars argue that the "mills" "are churches and not the factories of the Industrial Revolution everyone else takes them for".[13]

Revolution[edit]

Several of Blake's poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: "As all men are alike (tho' infinitely various)". He retained an active interest in social and political events for all his life, but was often forced to resort to cloaking social idealism and political statements in Protestant mystical Wikipedia:allegory. Even though the poem was written during the Wikipedia:Napoleonic Wars, Blake was an outspoken supporter of the Wikipedia:French Revolution, whose successor Wikipedia:Napoleon claimed to be.Template:Clarify[14] The poem expressed his desire for radical change without overt sedition. (In 1803 Blake was charged at Wikipedia:Chichester with high treason for having 'uttered seditious and treasonable expressions', but was acquitted.[15]) The poem is followed in the preface by a quotation from Numbers ch. 11, v. 29: "Would to God that all the Lord's people were prophets." Christopher Rowland, a Professor of Theology at Oxford University, has argued that this includes

everyone in the task of speaking out about what they saw. Prophecy for Blake, however, was not a prediction of the end of the world, but telling the truth as best a person can about what he or she sees, fortified by insight and an "honest persuasion" that with personal struggle, things could be improved. A human being observes, is indignant and speaks out: it's a basic political maxim which is necessary for any age. Blake wanted to stir people from their intellectual slumbers, and the daily grind of their toil, to see that they were captivated in the grip of a culture which kept them thinking in ways which served the interests of the powerful.[16]

The words of the poem "stress the importance of people taking responsibility for change and building a better society 'in England's green and pleasant land.'"[16]

The poem was inspired by the apocryphal story that a young Jesus, accompanied by his uncle Wikipedia:Joseph of Arimathea, travelled to the area that is now England and visited Wikipedia:Glastonbury during Jesus' lost years.[17] The legend is linked to an idea in the Wikipedia:Book of Revelation (3:12 and 21:2) describing a Wikipedia:Second Coming, wherein Jesus establishes a Wikipedia:new Jerusalem. The Christian Church in general, and the English Church in particular, used Jerusalem as a metaphor for Heaven, a place of universal love and peace.[18]

In the most common interpretation of the poem, Blake implies that a visit of Jesus would briefly create heaven in England, in contrast to the "dark Satanic Mills" of the Wikipedia:Industrial Revolution. Analysts note that Blake asks four questions rather than asserting the historical truth of Christ's visit; According to this view, the poem says that there may, or may not, have been a divine visit, when there was briefly heaven in England.[19][20]

"Chariot of fire"[edit]

The line from the poem, "Bring me my Chariot of fire!" draws on the story of 2 Kings 2:11, where the Wikipedia:Old Testament prophet Elijah is taken directly to heaven: "And it came to pass, as they still went on, and talked, that, behold, there appeared a chariot of fire, and horses of fire, and parted them both asunder; and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven." The phrase has become a byword for divine energy, and inspired the title of the 1981 film, Wikipedia:Chariots of Fire.

"Green and pleasant Land"[edit]

Blake lived in London for most of his life, but wrote much of Milton when he was living in the village of Wikipedia:Felpham in Sussex. Amanda Gilroy argues that the poem is informed by Blake's "evident pleasure" in the Felpham countryside.[21]

The phrase "green and pleasant land" has become a Wikipedia:collocation for identifiably English landscape or society. It appears as a headline, title or sub-title in numerous articles and books. Sometimes it refers, whether with appreciation, nostalgia or critical analysis, to idyllic or enigmatic aspects of the English countryside.[22] In other contexts it can suggest the perceived habits and aspirations of rural middle-class life.[23] Sometimes it is used ironically.[24]

Popularisation[edit]

The poem, which was little known during the century which followed its writing,[25] was included in the patriotic anthology of verse The Spirit of Man, edited by Great Britain's Wikipedia:Poet Laureate, Wikipedia:Robert Bridges, and published in 1916, at a time when morale had begun to decline because of the high number of casualties in World War I and the perception that there was no end in sight.[26]

Under these circumstances, Bridges, finding the poem an appropriate hymn text to "brace the spirit of the nation [to] accept with cheerfulnes all the sacrifices necessary,"[27] asked Sir Hubert Parry to put it to music for a Fight for Right campaign meeting in London's Wikipedia:Queen's Hall. (The aims of this organisation were "to brace the spirit of the nation, that the people of Great Britain, knowing that they are fighting for the best interests of humanity, may refuse any temptation, however insidious, to conclude a premature peace, and may accept with cheerfulness all the sacrifices necessary to bring the war to a satisfactory conclusion".)[28] Bridges asked Parry to supply "suitable, simple music to Blake's stanzas – music that an audience could take up and join in", and added that, if Parry could not do it himself, he might delegate the task to Wikipedia:George Butterworth.[29]

The poem's idealistic theme or Wikipedia:subtext accounts for its popularity across the philosophical spectrum. It was used as a campaign slogan by the Labour Party in the 1945 general election; Wikipedia:Clement Attlee said they would build "a new Jerusalem".[30] It has been sung at conferences of the British Conservative Party, at the Glee Club of the British Wikipedia:Liberal Assembly, the British Labour Party and by the British Wikipedia:Liberal Democrats.

Parry's setting of "Jerusalem"[edit]

In adapting Blake's poem as a unison song, Parry deployed a two-Wikipedia:stanza format, each taking up eight lines of Blake's original poem. He also provided a four-bar musical introduction to each verse and a coda, echoing melodic motifs of the song. (The song is always performed with these 'extra' passages.) And the word "those" was substituted for "these" (before "dark satanic mills".)

The song was first called "And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time" and the early published scores have this title. The change to 'Jerusalem' seems to have been made about the time of the 1918 Suffrage Demonstration Concert, perhaps when the orchestral score was published (Parry's manuscript of the orchestral score has the old title crossed out and 'Jerusalem' inserted in a different hand).[31]

See also[edit]

- Wikipedia:Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion by William Blake

- Wikipedia:Civil religion

- Wikipedia:Merry England

- Romantic Movement and the industrial revolution

- Wikipedia:Brain Salad Surgery (1973), with Wikipedia:Emerson, Lake & Palmer's version of "Jerusalem"

- The Internationale, Wikipedia:Billy Bragg's version

External links[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Cox, Michael, editor, The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature, "1808", p 289, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-860634-6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The William Blake Archive. Milton a Poem, copy B, object 2 (Bentley 2, Erdman 1 [i], Keynes 2) "Milton a Poem". http://www.blakearchive.org/.+URL accessed on 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Numbers 11:29. King James Version. biblegateway.com.

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. 1999 Poets in the Industrial Revolution. Wikipedia:The Engines of Our Ingenuity No. 1413: (Revised transcription)

- ↑ Walk This Way from southbanklondon.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ↑ ICONS – a portrait of England. Icon: Jerusalem (hymn) Feature: And did those feet? Accessed 7 August 2008

- ↑ Brian Maidment, Reading Popular Prints, 1790–1870, Manchester University Press, 2001, p.40

- ↑ Wikipedia:Alfred Kazin: Introduction to a volume of Blake. 1946

- ↑ Hall, Ernest In Defense of Genius. Annual Lecture to the Arts Council of England. 21st Century Learning Initiative. URL accessed on 19 September 2009. Template:Dead link

- ↑ Wikipedia:Incipit of citation given in Hall, 1996: "And all the Arts of Life they changed into the Arts of Death in Albion. / The hour-glass contemned because its simple workmanship / Was like the workmanship of the Plowman and the water-wheel / That raises water into cisterns, broken and burned with fire / Because its workmanship was like the workmanship of the shepherd; / And in their stead intricate wheels invented, wheel without wheel / To perplex youth in their outgoings and to bind to labours in Albion."

- ↑ Wikipedia:N. T. Wright, Bishop of Durham. 23 June 2007 "Where Shall Wisdom be Found?" 175th anniversary of the founding of the University of Durham

- ↑ Blake, William, Milton: A Poem, plate 4.

- ↑ Peter Porter, The English Poets: from Chaucer to Edward Thomas, Secker and Warburg, 1974, p.198., quoted in Shivashankar Mishra, The Rise of William Blake, Mittal Publications, 1995, p.184.

- ↑ William Blake Spartacus Educational (schoolnet.co) – Accessed 7 August 2008

- ↑ William Blake (1757–1827). Kirjasto.sci.fi. URL accessed on 7 August 2008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Rowland, C. 2007 William Blake: a visionary for our time openDemocracy.net

- ↑ Icons – a portrait of England. Icon: Jerusalem (hymn) Feature: And did those feet? Accessed 7 August 2008

- ↑ The hymn 'Jerusalem the Golden with milk and honey blessed... I know not oh I know not what joys await me there....' uses Jerusalem for the same metaphor.

- ↑ ''The One Show''. BBC. URL accessed on 29 April 2011.

- ↑ John Walsh Wikipedia:The Independent 18 May 1996

- ↑ Gilroy, Amanda (2004). Green and Pleasant Land: English Culture and the Romantic Countryside, Peeters Publishers.

- ↑ "Eric Ravilious: Green and Pleasant Land," by Tom Lubbock, The Independent, 13 July 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ↑ "This green and pleasant land," by Tim Adams, The Observer, 10 April 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ↑ "Green and pleasant land?" by Jeremy Paxman, The Guardian, 6 March 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ↑ Carroll, James (2011). Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ↑ (January 1916) "Index" The Spirit of Man: An Anthology in English & French from the Philosophers & Poets, First, Longmans, Green & Co.. URL accessed 10 September 2012.

- ↑ Carroll, James (2011). Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ↑ Christopher Wiltshire (Former archivist, British Federation of Festivals for Music, Speech and Dance), Guardian newspaper 8 December 2000 Letters: Tune into Jerusalem's fighting history Wikipedia:The Guardian 8 December 2000.

- ↑ C. L.Graves, Hubert Parry, Macmillan 1926, p. 92

- ↑ Link to PBS script quoting Attlee in 1945 – Accessed 2008-08-07. Pbs.org. URL accessed on 29 April 2011.

- ↑ The manuscripts of the song with organ and with orchestra, and of Elgar's orchestration, are in the library of the Royal College of Music, London

Template:Use dmy datessimple:And did those feet in ancient time