Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

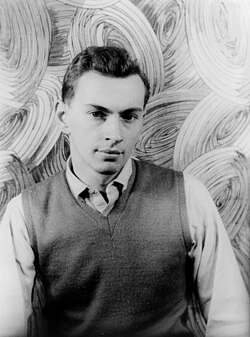

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal (born October 3 1925) (pronounced Template:IPA, occasionally Template:IPA, Template:IPA, etc) is an American author of novels, stage plays, screenplays, and essays. The scion of a prominent political family, Gore is a trenchant critic of the American political establishment. Gore wrote the The City and the Pillar in 1948, which created controversy as the first major American novel to feature unambiguous homosexuality.

Contents

Biography[edit]

He was born Eugene Luther Gore Vidal in West Point, New York, the only child of Eugene Luther Vidal Sr. (1901–1969) and the former Nina S. Gore (1903–1978). His birth took place at the Cadet Hospital of the United States Military Academy, where his father was the school's first aeronautics instructor, and he was christened by the headmaster of St. Albans, the preparatory school he would attend in his youth.[1] His second middle name honors his maternal grandfather, Thomas P. Gore, Democratic senator from Oklahoma.

Vidal's father, a "brawny, handsome" former West Point all-American quarterback who became the director of Commerce Department's Bureau of Air Commerce from 1933 until 1937 during the Roosevelt administration,[2] was one of the first Army Air Corps pilots and according to biographer Susan Butler was "the great love of Amelia Earhart's life".[3] He also was a cofounder of three American airlines in the 1920s and 1930s: the Ludington Line (which merged with other companies to become Eastern Airlines), Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT, which eventually became TWA), and Northeast Airlines (which he founded with Amelia Earhart and the Boston and Maine Railroad). Gene Vidal also was a veteran of the Olympics games of 1920 (where he placed seventh in the decathlon) and 1924 (where he coached the U.S. pentathlon teams).[4][5]

Nina, Vidal's alcoholic mother, was a onetime actress who made her Broadway debut in the 1928 production "Sign of the Leopard".[6] She married twice after her 1935 divorce from Gene Vidal (one husband was Hugh D. Auchincloss, the eventual stepfather of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis) and, according to her son, she had "a long off-and-on affair" with Clark Gable.[7] She served as an alternate delegate to the Democratic National Convention of 1940.[8] Vidal had four half-siblings from his parents' later marriages (the Rev. Vance Vidal, Valerie Vidal Hewitt, Thomas Gore Auchincloss, and Nina Gore Auchincloss Steers Straight, who was married to the onetime spy Michael Straight) and five stepsiblings from his mother's third marriage to Army Air Corps major general Robert Olds, father of legendary fighter ace Brigadier General Robin Olds. His nephew Burr Steers is a writer and film director, while his nephew Hugh Auchincloss Steers (1963–1995) was a painter whose works are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Walker Art Center, and the Denver Art Museum.

Vidal was raised in Washington, D.C., where he attended St. Albans School. Since Senator Gore was blind, the young Vidal read aloud to him and became his guide, thereby gaining an access, unusual for a child, to the corridors of power. The senator's steadfast isolationism contributed to one of the major principles underlying Vidal's political philosophy, which has been consistently critical of what he perceives as a foreign (and, by extension, a domestic) policy shaped by the imperatives of American imperialism. After graduating from Phillips Exeter Academy, Vidal joined the US Army Reserve in 1943.

For much of the late twentieth century, Vidal divided his time between Ravello, Italy, on the Amalfi Coast and Los Angeles, California. In 2003, he sold his 5,000 square foot (460 m²) cliffside Ravello villa (La Rondinaia, The Swallow's Nest) for health reasons, and currently resides in Los Angeles. In November 2003, Howard Austen, Vidal's life partner, died. In February 2005 Austen was buried in a plot maintained for Austen and Vidal at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Vidal is an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society.

Writing career[edit]

Fiction[edit]

The man, whom a Newsweek critic later described as "the best all-around man of letters since Edmund Wilson", began his writing career at age of twenty-one with publication of the novel Williwaw, based upon his military experiences in the Alaskan Harbor Detachment; conventionally realistic, the novel was well-received. A few years later, his pioneering novel The City and the Pillar, candidly dealing with gay themes, caused a furor, and The New York Times refused to review his next five books; the novel was dedicated to "J.T."

After a magazine published rumors about J.T.'s identity, Vidal eventually confirmed they referred to his St. Albans love, Jimmie Trimble, who had been killed in the Battle of Iwo Jima on June 1, 1945. He later claimed Trimble was the only person with whom he had ever been in love. Subsequently, as sales of his novels diminished, Vidal wrote plays, films, and television series as a scriptwriter. Two such plays, The Best Man and Visit to a Small Planet, were Broadway successes and later successful movies.

In the early 1950s, writing under the pseudonym 'Edgar Box', he wrote three mystery novels about a fictional public relations man named "Peter Cutler Sargeant II".

In 1956, Vidal was hired as a contract screenwriter for MGM. In 1959, director William Wyler needed re-writing of the Ben-Hur script, written by Karl Tunberg. Vidal collaborated with Christopher Fry, reworking the screenplay on condition that MGM release him from the last two years of his contract. Producer Sam Zimbalist's death complicated the screenwriting credit. The Screenwriters Guild resolved the matter by listing Tunberg as sole screenwriter, denying credit to both Vidal and Fry. Actor Charlton Heston was displeased with the veiled homosexuality of a scene Vidal wrote and denies that Vidal contributed significantly to the script ([1]).

In the 1960s, Vidal wrote three highly successful novels. The first, the meticulously researched Julian (1964) dealt with the apostate Roman emperor, while the second, Washington, D.C. (1967) focused on a political family during the Franklin D. Roosevelt era.

Vidal's third novel in the '60s was as daring as it was unexpected and outlandish; the satirical transsexual comedy Myra Breckinridge (1968), an inventive, often hilarious variation on familiar Vidalian themes of sex, gender, and popular culture. In the novel, Vidal showcased his love of the American films of the '30s and '40s, and he resurrected interest in the careers of the forgotten players of the time including, for example, Richard Cromwell, of whom he wrote, "was so satisfyingly tortured in The Lives of a Bengal Lancer."

After two commercially unsuccessful plays, Weekend (1968) and An Evening With Richard Nixon (1972), and the largely unappreciated novel Two Sisters, Vidal focused on essays and two distinct strains in his fiction. The first strain comprises novels dealing with American history, specifically with the nature of national politics. Critic Harold Bloom wrote, "Vidal's imagination of American politics . . . is so powerful as to compel awe." This series' titles include Burr (1973), 1876 (1976), Lincoln (1984), Empire (1987), Hollywood (1989), The Golden Age (2000), and another excursion into the ancient world Creation (1981, published in expanded form 2002).

The second strain consists of the comedic and often merciless "satirical inventions": Myron (1975, a sequel to Myra Breckinridge), Kalki (1978), Duluth (1983), Live from Golgotha: the Gospel according to Gore Vidal (1992), and The Smithsonian Institution (1998).

Vidal occasionally returned to scriptwriting cinema and television, including the television movie Billy the Kid with Val Kilmer, and the mini-series Lincoln. He also wrote the original draft for the controversial film Caligula, but later had his name removed because director Tinto Brass and actor Malcolm McDowell re-wrote the script, changing the tone and themes significantly. The producers later made a futile attempt to salvage some of Vidal's vision during post-production.

Essays and memoirs[edit]

Contrary to his wishes, Vidal is — at least in the U.S. — more respected as an essayist than as a novelist. The critic John Keates, echoing the general, if grudging, consensus, praised him as "this [the twentieth] century's finest essayist." Even an occasionally hostile critic like Martin Amis has admitted, "Essays are what he is good at . . . [h]e is learned, funny and exceptionally clear-sighted. Even his blind spots are illuminating."

Accordingly, for six decades, Gore Vidal has applied his wit, intelligence, polymathy, and inimitable voice to a wide variety of socio-political, sexual, historical, and literary themes. In 1987, Vidal wrote the essays titled Armageddon?, exploring the intricacies of power in contemporary America and ruthlessly pilloried the incumbent president Ronald Reagan as a "triumph of the embalmer's art." In 1993, he won the National Book Award for United States (1952 – 1992), the citation noting: "Whatever his subject, he addresses it with an artist's resonant appreciation, a scholar's conscience, and the persuasive powers of a great essayist." A subsequent collection of essays, published in 2000, is The Last Empire. Since then, he has published such self-described "pamphlets" as Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, Dreaming War: Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta,and Imperial America, powerful critiques of American expansionism, the military-industrial complex, the national security state, and the current administration. Vidal also wrote an historical essay about the U.S.'s founding fathers, Inventing A Nation. In 1995, he published a critically well-received memoir Palimpsest, and in 2006 its follow-up volume, Point to Point Navigation. Earlier that year, Vidal also published Clouds and Eclipses: The Collected Short Stories.

Because of his matter-of-fact treatment of homosexual relations in such books as The City and The Pillar, Vidal is often seen as an early and unrelenting champion of sexual liberation. Sexually Speaking: Collected Sex Writings, a representative sampling of his views, contains literary and cultural essays that document his long campaign to mock and subvert conventional American attitudes toward sex. Focusing on the anti-sexual heritage of Judaeo-Christianity, irrational and destructive sex laws, feminism, "heterosexism", homophobia, gay liberation, and pornography, the essays frequently return to a favorite Vidal motif: the fluidity of sexual identity. Vidal argues that "although our notions about what constitutes correct sexual behavior are usually based on religious texts, those texts are invariably interpreted by the rulers in order to keep control over the ruled." In repudiating this kind of rigid, narrow moralism, Vidal argues that "sex is a continuum" made up of "different phases along life’s way" and thus "everyone is potentially bisexual." He explains that "the human race is divided into male and female. Many human beings enjoy the sexual relations with their own sex, many don't; many respond to both. The plurality is the fact of our nature and not worth fretting about." Therefore, "there are no homosexual people, only homosexual acts." Given the diversity of human desire, Vidal predictably resists any effort to categorize him as exclusively "homosexual"---either as writer or human being---and instead celebrates this polymorphous eroticism as natural and inevitable.

Acting and publicity-seeking[edit]

In the 1960s, Vidal moved to Italy; he was cast as himself in Federico Fellini's film Roma. In 1992, Vidal appeared in the film Bob Roberts (starring Tim Robbins) and has appeared in other films, notably Gattaca, With Honors, and Igby Goes Down. Like his gruffer contemporary Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal is noted as a clever and tireless self-publicist. In an interview he stated: "[t]here is not one human problem that could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise". In 2005, Jay Parini was appointed as Vidal's literary executor.

Political views and activities[edit]

Besides his politician grandfather, Vidal has other connections to the Democratic Party: his mother Nina married Hugh D. Auchincloss, Jr., who later was stepfather of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. Gore Vidal is a fifth cousin of Jimmy Carter, and claims to be a distant cousin of Al Gore.[unverified]

As a political activist, in 1960, Gore Vidal was an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for Congress, losing an election in New York's 19th congressional district, a traditionally Republican district on the Hudson River, encompassing all of Columbia, Dutchess, Greene, Schoharie, and Ulster Counties, by a margin of 57% to 43%.[9] Campaigning with a slogan of "You'll get more with Gore", he received the most votes any Democrat in 50 years received in that particular district. From 1970 to 1972, he was one of the chairmen of the People's Party, and, with a half-million votes, he finished second to incumbent Governor Jerry Brown in California's 1982 Democratic primary election to the United States Senate. Vidal's Senate bid had the backing of liberal celebrities such as Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. The campaign was documented in the film, Gore Vidal: The Man Who Said No directed by Gary Conklin.

Although frequently identified with Democratic causes and personalities, Vidal has written: "[t]here is only one party in the United States, the Property Party . . . and it has two right wings: Republican and Democrat. Republicans are a bit stupider, more rigid, more doctrinaire in their laissez-faire capitalism than the Democrats, who are cuter, prettier, a bit more corrupt — until recently... and more willing than the Republicans to make small adjustments when the poor, the black, the anti-imperialists get out of hand. But, essentially, there is no difference between the two parties." Vidal's political views — characterized either as "liberal or progressive", and best described as radical in their disdain for privilege and power — are well-documented.

Vidal has a protective, almost proprietary attitude toward his native land and its politics. "My family helped start [this country]", he has written, "and we've been in political life... since the 1690s, and I have a very possessive sense about this country." Vidal considers himself a "radical reformer" wanting to return to the "pure republicanism" of early America. As a prep school student, he was a supporter of the America First Committee; unlike other America First Committee supporters, he continues in the opinion that the United States should not have entered World War II, (though acknowledging material assistance to the Allies was a good idea). He has suggested that President Roosevelt incited the Japanese to attack the U.S. to facilitate American entry to the war, and believes FDR had advance knowledge of the attack.

In 1968, ABC News hired Vidal and William F. Buckley, Jr. as political analysts of the Republican and Democratic presidential conventions, predicting that television viewers would enjoy seeing two men of letters — famous for their acerbic wit and sarcasm — engage in on-air battle; as it turned out, verbal and nearly physical combat were joined. After days of mutual bickering that devolved to childish, ad hominem attacks, Vidal called Buckley a "pro-crypto Nazi", to which the visibly livid Buckley replied: "Now listen, you queer. Stop calling me a crypto Nazi, or I'll sock you in the goddamn face and you'll stay plastered."

Later, in 1969, Buckley apologized to Vidal in the lengthy essay, "On Experiencing Gore Vidal", published in the August 1969 issue of Esquire; the essay is collected in The Governor Listeth, an anthology of Buckley's writings of the time. In a key passage attacking Vidal as an apologist for homosexuality, Buckley wrote: "the man who in his essays proclaims the normalcy of his affliction [i.e., homosexuality], and in his art the desirability of it, is not to be confused with the man who bears his sorrow quietly. The addict is to be pitied and even respected, not the pusher."

Not to be outdone, Vidal responded in the September 1969 issue of Esquire, variously characterizing William F. Buckley as "anti-black", "anti-semitic", and a "warmonger" ([2]). The presiding judge in Buckley's subsequent libel suit against Vidal initially concluded that "[t]he court must conclude that Vidal's comments in these paragraphs meet the minimal standard of fair comment. The inferences made by Vidal from Buckley's [earlier editorial] statements cannot be said to be completely unreasonable." However, Vidal also strongly implied that, in 1944, Buckley and unnamed siblings had vandalized a Protestant church in their Sharon, Connecticut, hometown after the pastor's wife had sold a house to a Jewish family. Buckley sued Vidal and Esquire magazine for libel; Vidal counter-claimed for libel against Buckley, citing Buckley's characterization of Vidal's novel Myra Breckinridge as pornography.

The court dismissed Vidal's counter-claim; Buckley settled for $115,000 in attorney's fees and an editorial statement from Esquire magazine that they were "utterly convinced" of the untruthfulness of Vidal's assertion. However, in a letter to Newsweek magazine, the Esquire publisher stated that "the settlement of Buckley's suit against us" was not "a 'disavowal' of Vidal's article. On the contrary, it clearly states that we published that article because we believed that Vidal had a right to assert his opinions, even though we did not share them."

As Vidal biographer, Fred Kaplan, later commented, "The court had 'not' sustained Buckley's case against Esquire... [t]he court had 'not' ruled that Vidal's article was 'defamatory.' It had ruled that the case would have to go to trial in order to determine as a matter of fact whether or not it was defamatory. [italics original.] The cash value of the settlement with Esquire represented 'only' Buckley's legal expenses [not damages based on libel]... " ultimately, Vidal bore the cost of his own attorney's fees, estimated at $75,000.

In 2003, this affair re-surfaced when Esquire published Esquire's Big Book of Great Writing, an anthology that included Vidal's essay. Buckley again sued for libel, and Esquire again settled for $55,000 in attorney's fees and $10,000 in personal damages to Buckley.

Vidal has stirred controversy with his relations with Timothy McVeigh. The two began corresponding while McVeigh was imprisoned; Vidal believes McVeigh either had accomplices or was framed for the Oklahoma City terrorist attack. Vidal also has suggested that the attack may have been carried out by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in order to promote legislation of stronger anti-terrorist laws. In another interview, he said Timothy McVeigh had bombed the federal building as retribution for the FBI's role in "spying on and murdering Americans." [unverified]

Vidal is a member of the advisory board of the World Can't Wait organization, which demands the impeachment of George W. Bush, and the charging of his administration with crimes against humanity ([3]).

During an interview in the 2005 documentary, Why We Fight, Vidal claims that during the final months of World War II, the Japanese had tried to surrender to the United States, but to no avail. He said, "They were trying to surrender all that summer, but Truman wouldn't listen, because Truman wanted to drop the bombs." When the interviewer asked why, Vidal replied, "To show off. To frighten Stalin. To change the balance of power in the world. To declare war on Communism. Perhaps we were starting a pre-emptive world war." Though Japan did sue for peace, the surrender to which Vidal referred was not their famous unconditional surrender after the bombing of Nagasaki, but rather one with status quo ante bellum terms that would have averted, among other things, military occupation.

Views on September 11, 2001 attacks against the United States[edit]

Vidal is strongly critical of the George W. Bush administration, listing it among administrations he considers to have either an explicit or implicit expansionist agenda. He frequently has made the point in interviews, essays, and in a recent book that Americans "are now governed by a junta of Oil–Pentagon men... both Bushes, Cheney, Rumsfeld, and so on."

He claims that for several years, this group and their associates have aimed to control the oil of central Asia (after, in his view, gaining effective control of the oil of the Persian Gulf in 1991). Specifically regarding the September 11, 2001 attacks, Vidal writes how such an attack, which he claims American intelligence warned was coming, politically justified the plans that the administration already had in August 2001 for invading Afghanistan the following October.

The factors Vidal cites in support of his theory include NORAD's purported delay in mobilizing fighter airplanes to intercept the hijacked airliners. If these failures resulted from incompetence, he says, they would deserve "a number of courts martial with an impeachment or two thrown in." Instead, there was only a limited inquiry into how the "potential breakdowns among federal agencies... could have allowed the terrorist attacks to occur."

Vidal concluded that it was possible that the administration let the attacks happen.

On October 24, 2006, Gore Vidal expanded on these views on the Alex Jones Show, stating that he was certain that the Bush administration had "let it happen on purpose." ([4])

Trivia[edit]

- Vidal was portrayed briefly in the film Infamous (2006) by Michael Panes.

- Vidal was the inspiration for the character Brinker Hadley in John Knowles's book A Separate Peace. Vidal and Knowles attended the Phillips Exeter Academy together.

- Vidal appeared on Da Ali G Show to talk about history and rhyme some lyrics that Ali G wrote. Ali G confused him with Vidal Sassoon.

- Vidal has voiced himself on both The Simpsons and Family Guy.

References[edit]

- ↑ Gore Vidal, Point to Point Navigation (New York: Doubleday, 2006), p. 245.

- ↑ "Aeronatics: $8,073.61", Time, 28 September 1931

- ↑ http://www.booknotes.org/Transcript/?ProgramID=1391

- ↑ "Eugene L. Vidal, Aviation Leader", The New York Times, 21 February 1969, p. 43

- ↑ South Dakota Sports Hall of Fame Profile: Gene Vidal

- ↑ "General Robert Olds Marries", The New York Times, 7 June 1942, p. 6

- ↑ Gore Vidal, Point to Point Navigation, New York: Doubleday, 2006, p. 135.

- ↑ http://www.politicalgraveyard.com/bio/aubert-austen.html

- ↑ clerk.house.gov 1960 election p.31

Bibliography[edit]

Essays and non-fiction[edit]

- Rocking the Boat (1963)

- Reflections Upon a Sinking Ship (1969)

- Sex, Death and Money (1969) (paperback compilation)

- Homage to Daniel Shays (1972)

- Matters of Fact and of Fiction (1977)

- The Second American Revolution (1982)

- Armageddon? (1987) (UK only)

- At Home (1988)

- A View From The Diner's Club (1991) (UK only)

- Screening History (1992) ISBN 0-233-98803-3

- Decline and Fall of the American Empire (1992) ISBN 1-878825-00-3

- United States: essays 1952–1992 (1993) ISBN 0-7679-0806-6

- Palimpsest: a memoir (1995) ISBN 0-679-44038-0

- Virgin Islands (1997) (UK only)

- The American Presidency (1998) ISBN 1-878825-15-1

- Sexually Speaking: Collected Sex Writings (1999)

- The Last Empire: essays 1992–2000 (2001) ISBN 0-375-72639-X (there is also a much shorter UK edition)

- Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace or How We Came To Be So Hated, Thunder's Mouth Press, 2002, (2002) ISBN 1-56025-405-X

- Dreaming War: Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta, Thunder's Mouth Press, (2002) ISBN 1-56025-502-1

- Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson (2003) ISBN 0-300-10171-6

- Imperial America: Reflections on the United States of Amnesia (2004) ISBN 1-56025-744-X

- Point to Point Navigation : A Memoir (2006) ISBN 0-385-51721-1

Plays[edit]

- Visit to a Small Planet (1957) ISBN 0-8222-1211-0

- The Best Man (1960)

- On the March to the Sea (1960–1961, 2004)

- Romulus (adapted from Friedrich Duerrenmatt's play) (1962)

- Weekend (1968)

- Drawing Room Comedy (1970)

- An evening with Richard Nixon (1970) ISBN 0-394-71869-0

- On the March to the Sea (2005)

Novels[edit]

- Williwaw (1946) ISBN 0-226-85585-6

- In a Yellow Wood (1947)

- The City and the Pillar (1948) ISBN 1-4000-3037-4

- The Season of Comfort (1949) ISBN 0-233-98971-4

- A Search for the King (1950) ISBN 0-345-25455-4

- Dark Green, Bright Red (1950) ISBN 0-233-98913-7 (prophecy of the Guatemala coup d'etat of 1954, see "In the Lair of the Octopus" Dreaming War)

- The Judgment of Paris (1952) ISBN 0-345-33458-2

- Messiah (1954) ISBN 0-14-118039-0

- A Thirsty Evil (1956) (short stories)

- Julian (1964) ISBN 0-375-72706-X

- Washington, D.C. (1967) ISBN 0-316-90257-8

- Myra Breckinridge (1968)

- Two Sisters (1970) ISBN 0-434-82958-7

- Burr (1973) ISBN 0-375-70873-1

- Myron (1975) ISBN 0-586-04300-4

- 1876 (1976) ISBN 0-375-70872-3

- Kalki (1978) ISBN 0-14-118037-4

- Creation (1981) ISBN 0-349-10475-1

- Duluth (1983) ISBN 0-394-52738-0

- Lincoln (1984) ISBN 0-375-70876-6

- Empire (1987) ISBN 0-375-70874-X

- Hollywood (1989) ISBN 0-375-70875-8

- Live from Golgotha: the Gospel according to Gore Vidal (1992) ISBN 0-14-023119-6

- The Smithsonian Institution (1998) ISBN 0-375-50121-5

- The Golden Age (2000) ISBN 0-375-72481-8

- Clouds and Eclipses : The Collected Short Stories (2006) (short stories, this is the same collection as A Thirsty Evil (1956), with one previously unpublished short story - Clouds and Eclipses - added)

Under pseudonyms[edit]

- A Star's Progress (aka Cry Shame!) (1950) as Katherine Everard

- Thieves Fall Out (1953) as Cameron Kay

- Death Before Bedtime (1953) as Edgar Box

- Death in the Fifth Position (1952) as Edgar Box

- Death Likes It Hot (1954) as Edgar Box

Appearances and interviews[edit]

- Gore Vidal: The Man Who Said No (1982 documentary)

- Bob Roberts (1992 film)

- Gattaca (1997 film)

- Igby Goes Down - as a Catholic priest (2002 coming-of-age film directed by his nephew Burr Steers)

- Da Ali G Show (2004 episode)

- Thinking XXX (2004 documentary)

- Why We Fight (2005 film)

- Inside Deep Throat (2005 film)

- Foreign Correspondent - with former NSW premier Bob Carr

- The U.S. Versus John Lennon (2006 film)

- Family Guy - "Mother Tucker" (2006 Animated TV episode)

- The Simpsons - "Moe 'N' A Lisa" (2006 Animated TV episode)

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

| You can help Anarchopedia by expanding this article by adding some of these quotes from Wikiquote |

- [5] Gore Vidal Bio at Greater Talent Network (Speakers Bureau)

- [6] Gore Vidal and Dennis Altman speaking about Gore Vidal's America on November 7 2005 at [7] D.G. Wills Books in La Jolla, California, 86 min, in mp3 format

- [8] The Gore Vidal Index

- [9] Queer History: Who is Gore Vidal?

- [10] Interview in Salon, January 1998

- [11] C-SPAN Book TV In Depth 3 Hour Interview - October 1 2000; RealVideo format.

- [12], Interview in City Pages March 2005, "The Undoing of America"

- [13] The Gore Vidal Pages

- [14] Gore Vidal

- [15] The Ethical Spectacle, October 2005

- [16] The Ethical Spectacle, January 2006

- [17] 1992 Audio Interview with Gore Vidal - RealAudio

- [18] Tribute to Gore Vidal on his 80th Birthday - Pravda

- [19] Gore Vidal at 80 - RadioNation Interview, 16 October 2005

- [20] The Edge - Gore Vidal Interview, 21 December 2005

- [21], "I Do What I Think Needs Doing" - Vidal interview

- [22],"President Jonah" for Truthdig, 25 January 2006

- [23] The Paris Review interview

- [24], "Vidal Never More Vital", Doug Ireland's November 2005 In These Times article

- Interview with Vidal from Gadfly July 1999

- Vidal fields questions from Stanley Crouch, Marianne Faithfull, Michael Lind and others.

- 1992 audio interview with Gore Vidal by Don Swaim

- Clip from documentary film of Gore Vidal's 1982 run for U.S. Senate.

- [25] Gore power to you: a new PBS documentary examines the wonderfully uncensored political and literary life of Gore Vidal, The Advocate, July 22, 2003

- Gore Vidal IMDB profile including a list of his many screen writer credits

| This article is based on a GNU FDL LGBT Wikia article: Vidal Gore Vidal | LGBT |

- Articles needing peer review

- Pages with broken file links

- Stubs

- Living people

- American people

- American dramatists and playwrights

- American essayists

- American memoirists

- American novelists

- American screenwriters

- American tax resisters

- Edgar Award winners

- Bisexual writers from the United States

- Historical novelists

- History of United States isolationism

- LGBT screenwriters

- Phillips Exeter Academy alumni

- American expatriates in Italy