Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Abahlali baseMjondolo

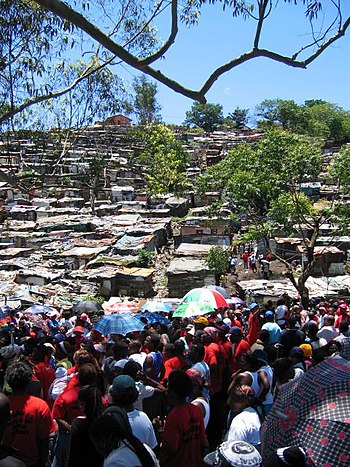

Abahlali baseMjondolo is a popular, entirely non-professionalized and democratic mass movement of shack dwellers and other poor people in South Africa. Abahlali take the view that 'if you live in the settlements you are from the settlements' and it is a multi-ethnic, multi-racial and multi-national movement. Women are prominently represented at all levels of the movement's structures and on 9 August 2008 it launched a Women's League.

The movement took a strong stand against the xenophobic attacks that swept the country[1] in May 2008 and there were no attacks in any Abahlali settlements. The movement was also able to stop an in progress attack in the (non-Abahlali affiliated) Kenville settlement and to offer shelter to some people displaced in the attacks.

The movement grew out of a road blockade[2] organized from the Kennedy Road shack settlement in the city of Durban in early 2005[3][4] and now operates across the provinces of KwaZulu-Natal and the Northern Cape as well as in in Cape Town. The words Abahlali baseMjondolo are isiZulu for people who stay in shacks.

Abahlali refuses to participate in party politics[5][6]or any NGO style professionalization or individualization of struggle and instead seeks to build democratic people's power where people live and work. [7] It has placed the dignity of the poor at the centre of its politics.

Abahlali has members in 36 shack settlements[8], some blocks of flats, some rural areas and amongst some street traders. Twenty four of these branches participate in the movement on a day to day basis. The others tend to only be active in times of crises or heightened political temperature. Most of the settlements affiliated to the movement are in and around the cities of Durban, Pinetown and Pietermartizburg. There are also branches in other towns like Port Shepstone, Ermelo and Tongaat and there are also Abahlali members in Cape Town.[9]

Although it is a largely regional rather than a national movement Abahlali is often referred to as by far the largest oppositional movement of the poor to have emerged outside of the ANC alliance thus far in post-apartheid South Africa. Like other squatter's movements such as the Landless Peoples' Movement in Jo'burg and the Anti-Eviction Campaign in Cape Town Abahlali have been subject to severe and sustained state repression suffering numerous police beatings and more than 200 arrests over the last three years.[10]. Not one of these arrests has ever resulted in a conviction and the movement is currently suing the police with the support of Amnesty International. Abahlali claims that it has been subject to sustained illegal police harassment, violence and intimidation. It has received very strong support from very senior church leaders on the issue of police harassment.[11] Journalists covering Abahlali protests have also reported violent intimidation, theft of cameras and wrongful arrest by the police.

The movement has a very high media profile, especially in the isiZulu media and on local radio and received strong support from the churches.[12]

Abahlali baseMjondolo works very closely with the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign, a grassroots movements of the poor based in Cape Town. Both movements are notable for insisting that the NGO left respect the autonomy and internal democracy of grassroots poor people's movements and 'speak to and not for' the movements. AbM also has links to the Landless Peoples' Movement in Johannesburg.

Contents

Context[edit]

The eThekwini Municipality which governs Durban and Pinetown has embarked on a slum clearance programme which means the steady demolition of shack settlements and a refusal to provide basic services (e.g. electricity, sanitation etc) to existing settlements on the grounds that all shack settlements are now 'temporary'. In these demolitions some shack dwellers are simply left homeless and others are subject to forced evictions to the rural periphery of the city. Abahlali is primarily committed to opposing these demolitions and forced removals and to fighting for good land and quality housing in the cities. In most instances this takes the form of a demand for shack settlements to be upgraded where they are or for new houses to be built close to where the existing settlements are. However the movement has also argued that basic services such as water, electricity and toilets should be immediately provided to shack settlements while land and housing in the city are negotiated. The movement has had a considerable degree of success in stopping evictions and forced removals, has had some success in winning the right for new shacks to be built as settlements expand and in winning access to basic services but has not yet been able to win secure access to good urban land for quality housing.

From its origins in a rejection of the representative role of local councillors, Abahlali have also argued very strongly for direct popular democracy (i.e. popular counter power) as a goal and mode of struggle. In practice this has meant democratising settlements that were run on the basis of various forms of authoritarianism, refusing to participate in (state) electoral politics and seeking to force all would be representatives of the poor (in government, NGOs, churches, universities etc) to 'speak to us, not for us' with a view to building the power of the poor against the rich rather than advocating for a counter elite who will represent the poor against the rich. Abahlali has had great success in building popular power outside of the representative politics that characterises both the councillor system and certain modes of NGO politics and in winning the right for the poor to speak for themselves in the media and in various kinds of engagements and encounters. However in a number of settlements the struggle against unelected authoritarian (and often armed) local elites, who often try to deliver the settlement to a political party in exchange for petty favours, has not been successful and Abahlali branches can not easily organise openly. In some of these settlements there are ongoing struggles for democratisation. In some instances people struggling for democratisation are living under death threats.

The movement's red t-shirts have become famous and Abahlali is often simply known as Izikipa ezibomvu (the red shirts). In 2006 individuals in the state, and linked to a local NGO, alleged that the shirts are provided by some nefarious source. But Abahlali members, as well as visiting academics who have spent time with the movement, and some journalists, report that the shirts are, in fact, most often made in the shacks on rented pedal power sewing machines by the Abahlali Women's Sewing Collective. Where there has been funding for the t-shirts it has come from local churches who have, since, late 2006, offered sustained support to the movement - mostly in the form of physical presence on marches and so on. Church leaders have also been assaulted by the police on marches.

Activities of the movement[edit]

The movement is best known for having democratised the internal governance of many settlements (although these struggles continue in many settlements and are not resolved everywhere) and having organised numerous large marches on local councillors, as well as the mayor and the provincial Minister of Housing and high profile protests against a local police officer and the premier of KwaZulu-Natal. The organisation has also successfully fought against evictions and forced removals by mass mobilisation and court action; successfully used access to information law to force the city to reveal its plans for the forced removal of many shack settlements and its land holdings; demanded the electrification of shack settlements to stop the regular fires and trained people to make illegal electricity connections safely; trained people in computer skills; campaigned for access to water and sanitation; fought for land and housing in the city; started creches; campaigned for access to schools and around language issues in schools; held quarterly all night music, poetry and drama evenings; produced a number of choirs and bands that have developed explicitly political forms of various traditional musics; run a 16 team football league; provided HIV/AIDS care; started a ten thousand copies per issue newspaper; undertaken various education projects; vigorously opposed what it sees as authoritarianism from government, business and some NGOs (including left NGOs); won major and sustained media attention particularly in the Zulu language media; campaigned in support of shack dwellers in Zimbabwe and Haiti; campaigned for access to schools, sports facilities and libraries; won legal status for new shacks and for expanded shacks, and sought to win popular control over decision making that affects poor communities. Abahlali has produced 6 or 7 shack dwelling public intellectuals who regularly comment and, in some instances, write in the local media in English, Zulu and Xhosa.[13].

There were no evictions from or demolitions of shacks in Abahlali settlements from December 2006 till July 2007 when four new shacks were demolished in the Foreman Road settlement. This demolition was vigorously contested and the shacks have been rebuilt and successfully defended. In December 2007 18 shacks were illegally demolished in the Shannon Drive settlement. This settlement was not affiliated to Abahlali but Abahlali agree to support them anyway and the evictions were successfully halted via mass mobilisation. Shannon Drive has now affiliated to Abahlali. In January 2008 the City illegally demolished 4 shacks in the Arnett Drive settlement. Abahlali won a court interdict against the City and the demolitions were halted.

Abahlali is currently mobilising against the Slums Act, a new law that seeks to enable the rapid mass eviction of shackdwellers, to set up 'transit camps' in which to house evicted shackdwellers and to criminalizes all resistance to evictions.[14].

The movement has formal and vibrant relationships with the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign in Cape Town, the Combined Harare Residents' Association in Zimbabwe and a number of other community organisations. There are also connections to movements of the poor in Turkey and Haiti.

Key slogans of the movement are 'Sekwanele!' ('Enough!'), 'Talk to us, not for us!', 'Nothing for us without us!', and 'Umhlaba! Izindlu! (Land! Houses!).

Structure[edit]

Office holders at branch, settlement and movement level are elected annually in open assemblies. At least half of all elected positions are filled by women. Office holders are given mandates for action at open weekly meetings, are subject to recall and the secretariat can credibly claim to represent approximately 30,000 people. Every 3 months or at times of crisis there is a 'camp' - an all night meeting. People elected into office are not elected to make decisions on particular issues but rather to ensure democratic decision making on questions and matters related to those issues and to carry out mandates received this way. People who present the movement to the media and who travel to represent the movement elsewhere are always elected, mandated and rotated and at least half of the people elected to fulfil these responsibilities are women. At large assemblies male and female questioners and speakers are alternated. One of the movement's founding principles, which is regularly reaffirmed publicly, is that no one in the movement will ever make any money from the movement. The movement accepts no money from political parties, governments or from those NGOs which seek to use donor funding to substitute their own voices and projects for those of the poor and is 100% run by unpaid volunteers. Funds are raised by a small annual membership fee of R7 (1$ US) and occasional irregular small donations and are strictly used for movement (not individual) expenses such as transport, printing, bail costs etc. Donations have very often been refused and are only accepted when the movement's meetings (rather than the donor or an individual member of the movement) will have full control over how the money is used.

The movement has a number of sub-committees and internal organisations such as a Churches Sub-Committee, a Youth League, a Women's League, a Book Collective, etc, etc.

Philosophy[edit]

The movement's philosophy has been sketched out in a number of articles and interviews. The key ideas are those of a politics of the poor, a living politics and a people's politics. A politics of the poor is understood to mean a politics that is conducted by the poor and for the poor in a manner that enables the poor to be active participants in the struggles conducted in their name. Practically it means that such a politics must be conducted where poor people live or in places that they can easily access, at the times when they are free, in the languages that they speak. It does not mean that middle class people and organisations are excluded but that they are expected to come to these spaces and to undertake their politics here and in a dialogical and respectful manner. There are two key aspects to the idea of a living politics. The first is that it is understood as a politics that begins not from external theory but from the experience of the people that shape it. It is argued that political education usually operates to create new elites who mediate relationships of patronage upwards and who impose ideas on others and to exclude ordinary people from thinking politically. This politics is not anti-theory - it just asserts the need to begin from lived experience and to move on from there rather than to begin from theory (usually imported from the Global North) and to impose theory on the lived experience of suffering and resistance in the shacks. The second key aspect of a living politics is that political thinking is always undertaken democratically and in common. People's politics is opposed to party politics or politicians' politics (as well as to top down undemocratic forms of NGO politics) and it is argued that the former is a popular democratic project undertaken without financial reward and with an explicit refusal of representative roles and personal power while the latter is a top down, professionalised representative project driven by personal power. The movement has been particularly opposed to the Zuma project within the ANC because the settlements are very cosmopolitan and it has been feared that the ethnic overtones of the project are potentially damaging to the unity that has been built in the settlements.

The movement often but not always opens and closes its meetings with a prayer. It has engaged in theological debates internally and with churches. It is not linked to any particular church and welcomes various forms of religiosity. Most members are Christian but some are Muslim, Hindu and atheist and a Muslim person is just as likely to be asked to open a meeting with a prayer as a Christian person.

Harassment[edit]

In the early days of the movement individuals in the ruling party, including the eThekwini City Manager Mike Sutcliffe and Mayor Obed Mlaba and many others, often accused Abahlali of being criminals manipulated by a malevolent white man, a 'third force', or a foreign intelligence agency.[15] Similar claims have been made by people in and associated with two left NGOs that assume a right, often vigorously contested from below, to represent, lead and discipline poor people's movements. No empirical evidence was ever been adduced for these claims and they have been vigorously contested by all kinds of independent witnesses. However they created a climate that justified violent repression. Since then the state has developed much better intelligence and now appears to be very well aware of who the key movement people are in each settlement and to be targeting those people in various ways. The movement dismissed the assumption that it is 'driven' by a white man as insulting and both racist and classist.

The movement, like others in South Africa[16], has suffered sustained illegal harassment from the state[17][18][19] that has resulted in more than 200 arrests of Abahlali members over the last 3 years and repeated police violence in people's homes, in the streets and in detention. On a number of occasions the police used live ammunition, armoured vehicles and helicopters in their attacks on unarmed shack dwellers. In 2006 the local city manager, Mike Sutcliffe, unlawfully implemented a complete ban on Abahlali's right to march which was eventually overturned in court.[20][21] Abahlali have been violently prevented from accepting invitations to appear on television and radio debates by the local police. The movement has laid numerous assault, as well as theft and wrongful arrest charges against the police. In November 2006 Philani Zungu and S'bu Zikode were tortured in the Sydenham Police station. On 4 December 2006 a pregnant women lost her child and a man was killed when the police attacked residents of the Siyanda settlement who had blockaded a major road. Police harassment has been strongly condemned by human rights organisations including, most notably, the Freedom of Expression Institute which has issued a number of statements in strong support of Abahlali's right to speak out and to organise protests.[22]. The Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions [23] and a group of prominent church leaders[24][25] have also issued public statements against police violence and in support of the right of the movement to publicly express dissent.

Police violence against Abahlali has been quite widely covered in the mainstream international media (e.g The New York Times[26], The Times (London), The Economist, Le Monde etc). Not one of the arrests of Abahlali members has ever led to a trial and no member of Abahlali has ever been convicted of any offence. However at the moment (December 2007) 21 Abahlali members are out on bail on various charges.

A number of Abahlali members have come under major pressure at work due to their activities in the movement and some have been forced out of jobs in both the public and private sectors including S'bu Zikode[27][28], the current elected head of the movement and Philani Zungu.

Abahlali have organised against police brutality and after a march on Supt. Glen Nayager of the Sydenham Police Station in April 2005, a march that received strong church support, there was some improvement. Although there were arrests after that march (for connecting electricity illegally) no one has been assaulted while in police custody.[29]. However on 27 September 2007 the police, under the command of Glen Nayager, launched a violent and unprovoked attack[30]on a march of around 3 500 resulting in numerous injuries.[31]Ma Kikine, a frail elderly woman from the Joe Slovo settlement was shot 6 times in the back at close range with rubber bullets. For the first time clergy were also beaten by the police on this occasion.

However in Durban the City began a process of negotiation with the movement in early 2008 and since mid 2008 there have been no incidents of police harassment against the movement in that City.

International Condemnation of Repression in Durban[edit]

In late 2005 the New York Times reported that shack dwellers in the Foreman Road shanty town had burnt an effigy of Mlaba after they had been attacked by the police and illegally banned from staging a march on the mayor to protest against his housing policy. Since 2005 international human rights reports have regularly condemned abuses against shack dwellers in Durban including the illegal banning of protests and illegal police violence against peaceful protests. [32].

In September 2007 thousands of shack dwellers were peacefully marching on Mayor Mlaba to protest against his policy of expelling the poor from the city were violently attacked by the police without warning or provocation. The police attack was strongly condemned by South African church leaders and by international human rights organisations.[33]

A report by to the United Nations the Centre for Housing Rights in Geneva in early 2008 claims that the City routinely evicts shack dwellers without court orders.[34]

In early 2008 the United Nations expressed serious concern about the treatment of shack dwellers in Durban. [35] At the same time the Mercury newspaper reported that both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International were investigating Human Rights abuses against shack dwellers by the City Government of which Mlaba is the head.[36]

2010 World Cup[edit]

In the run-up to the 2010 World Cup, shack dwellers have been considered by some in government as a blight. City Hall has promised to 'clear the slums' by 2010 and there are real fears that in Durban, as in other South African cities like Cape Town, shack dwellers will face forced removals and evictions on a major scale in the run up to the World Cup. These fears have escalated greatly with the June 2007 passing of the Prevention of Slums Bill in the Provincial Parliament. The Bill compels landowners to evict on the threat of arrest and criminalises resistance to evictions. The provincial Department of Housing, that brought the Bill to the Provincial Parliament, has repeatedly stated that 'the slums will be cleared by 2010 in KwaZulu-Natal'. Abahlali is planning mass mobilizing against the Bill and is also taking the matter to the Constitutional Court with support from a pro bono legal legal centre in Johannesburg.

For further study[edit]

The situation in South Africa is not unique. There are many examples of similar settlements, be they called favelas, Bidonvilles, Gecekondu, Kartonsko naselje, flophouses, shanty towns, ghettos or colonias. Examples include New Village in Malaysia, Cité Soleil in Haiti, and Kibera in Kenya. For more information on shack settlements around the world, see the work of researchers Robert Neuwirth and Mike Davis as well as the special issues of Mute Magazine and the Journal of Asian and African Studies on shanty town struggles.

Membership based and directed shack dwellers' movements elsewhere include:

- The Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto (MTST) in Brazil.

- The Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign (WCAEC) in Cape Town.

Membership based and directed shack dwellers' movements in South Africa of historical interest:

- The Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union (ICU)

External links[edit]

- Abahlali baseMjondolo Website

- Abahlali baseMjondolo newswire

- A collection of articles by Abahlali baseMjondolo members

- Pictures by Abhalali women

- Picture & video galleries on Abahlali.org

- A Digital Archive of Abahlali baseMjondolo History from March 2005 to November 2006 (with links to pictures, articles, press releases etc) at the MetaMute site

- Magazine article giving a broad overview of the first 18 months of Abahlali baseMjondolo

- Articles by and on Abahlali baseMjondolo in Zulu

- Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign

Notes and references[edit]

- ↑ See http://www.abahlali.org/node/3582

- ↑ [1]Article in the Sunday Tribune newspaper by Fred Kockott describing the road blockade

- ↑ [2] Article by Richard Pithouse on the origins of the movement

- ↑ [3] Article by Jacob Byrant on the origins of the movement

- ↑ [4] Article by M'du Hlongwa examining the refusal of electoral politics in Abahlali

- ↑ [5], Article by Raj Patel examining the refusal of electoral politics in Abahlali

- ↑ [6] Article by Xin Wei Ngiam that includes interviews on conceptions of democracy amongst Abahlali militants

- ↑ [7] Article on Abahlali in Voices of Resistance from Occupied London

- ↑ [8] Abahlali press release detailing areas in which the movement has support

- ↑ [9] Press Release on police harassment

- ↑ [10] A statement against police violence against Abahlali by 11 church leaders

- ↑ statement of support from Bishop Ruben Phillip

- ↑ [11] A collection of online articles by Abahlali public intellectuals

- ↑ [12]The text of the Slums Bill plus various documents in response to it

- ↑ [13] Article by S'bu Zikode written in response to Third Force allegations

- ↑ See a report in illegal police repression in South Africa by the Freedom of Expression Institute

- ↑ [14] An eyewitness account of police violence in the Mail & Guardian newspaper

- ↑ [15] Article on police violence by System Cele

- ↑ [16] Article on police violence by Philani Zungu

- ↑ [17] Article in the Daily News

- ↑ Statement by the Freedom of Expression Institute

- ↑ [18] Freedom of Expression Institute statement

- ↑ [19]Open Letter to Obed Mlaba & Mike Sutcliffe by COHRE

- ↑ [20]Testimony by Church Leaders

- ↑ Sunday Tribune article on church leader's statement

- ↑ [21], New York Times article

- ↑ [22] Article by S'bu Zikode on being fired

- ↑ [23] Article by Nigel Gibson that includes a theorization of S'bu Zikode as political philosopher plus some biographical information

- ↑ [24] Pictures and memorandum from a protest against Nayager

- ↑ [25]Press statement on and photographs of the police attack

- ↑ [26]Injury list

- ↑ [See for instances the annual Human Rights Report at http://www.humanrights.uio.no/english/research/programmes/safrica/reports.xml]

- ↑ A collection of articles from various media sources on the march, the police attacked and its aftermath

- ↑ COHRE Report to the United Nations on Housing Rights Violations in Durban

- ↑ United Nations Statement on Housing Rights Violations in South Africa

- ↑ Mercury article by Imraan Buccus, 8 March 2008

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Abahlali baseMjondolo on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |

- Pages with broken file links

- Activism in South Africa

- Direct action in South Africa

- Direct action in Africa

- Affordable housing advocacy organizations

- Durban

- Homelessness organizations

- Social movements

- Protests in South Africa

- Protests in Africa

- Rebellions in Africa

- Multicultural feminism

- Organisations based in South Africa

- Pietermaritzburg

- South African social movements

- Social movements in Africa

- Urban studies and planning organisations

- Shack dwellers' movements

- Human habitats

- Slums