Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Nat Turner

Nat, remembered today as Nat Turner, 1800 (October 2 – 1831 November 11) was an American slave whose failed slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia, was the most remarkable instance of black resistance to enslavement in the antebellum southern United States. His methodical slaughter of white civilians during the uprising makes his legacy controversial, but he is still considered by many to be a heroic figure of black resistance to oppression. Though he became known as "Nat Turner" in the aftermath of the uprising, his actual given name was simply "Nat".

Contents

[hide]Early life

Nat was born in Southampton County, Virginia. He was singularly intelligent, picking up the ability to read at a young age and experimenting with homemade paper and gunpowder. He grew up deeply religious and was often seen fasting and praying. He frequently received visions which he interpreted as being messages from God, and which greatly influenced his life; for instance, when Nat was 21 years old he ran away from his master, but returned a month later after receiving such a vision. He became known among fellow slaves as "The Prophet".

On 1831 February 12, an annular solar eclipse was seen in Virginia. Nat took this to mean that he should begin preparing for a rebellion. The rebellion was initially planned for July 4, Independence Day, but was postponed due to deliberation between him and his followers and illness. On August 13, there was an atmospheric disturbance, a solar eclipse, in which the sun appeared bluish-green. Nat took this as the final signal, and a week later, on August 21, the rebellion began.

Rebellion

Nat started with a few trusted fellow slaves. The rebels traveled from house to house, freeing slaves and killing all the white people they found. The rebels ultimately included more than 50 slaves and free blacks.

Because the slaves did not want to alert anyone to their presence as they carried out their attacks, they initially used knives, hatchets, axes, and blunt instruments instead of firearms. Nat called on his group to "kill all whites." The rebellion did not discriminate by age or gender, although Nat later indicated that he intended to spare women, children, and men who surrendered as it went on. Before Nat and his brigade of slaves met resistance at the hands of a white militia, 57 white men, women and children had been killed. [1]

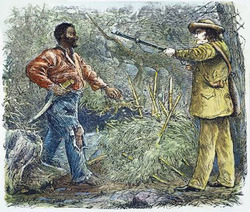

Capture and execution

Nat Turner's rebellion was suppressed within 48 hours, but Nat eluded capture until October 30 when he was discovered hiding in a cave and then taken to court. On November 5, 1831, Nat was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. He was hanged on November 11 in Jerusalem, Virginia, now known as Courtland, Virginia. His body was then flayed, beheaded and quartered, and various body parts were kept by whites as souvenirs. After his execution, his lawyer, Thomas Ruffin Gray, who had access to the jail in which Nat had been held, took it upon himself to publish The Confessions of Nat Turner, derived partly from research done while Nat was in hiding and partly from conversations with Nat before his trial.

This document is the primary historical document regarding Nat. However, its author's bias is problematic. It is probable that Gray suppressed some facts and gave undue emphasis to others. It seems unlikely, for example, that Nat would have said such things as, “we found no more victims to gratify our thirst for blood.†However, the book does contain other lines which appear genuine, particularly the passages in which Nat describes his visions and early childhood.

Consequences

Prior to the Nat Turner Revolt, there was a fairly substantial abolition movement in the state of Virginia, largely on account of economic trends that made slavery less profitable in the Old South in the 1820's and fears of the rising number of blacks in whites, especially in the Tidewater and Piedmont regions. Most of the movement's members, including acting governor John Floyd, supported resettlement for these reasons. Considerations of white racial and moral purity also influenced many of these abolitionists.

However, fears of repetitions of the Nat Turner Revolt served to polarize moderates and slave owners across the South. Municipalities across the region instituted repressive policies against slaves and free blacks. The freedoms of all black people in Virginia were tightly curtailed, and an official policy was established that forbade questioning the slave system on the grounds that any discussion might encourage similar slave revolts. There is evidence of trends in support of such policies and for slavery itself in Virginia before the revolt. This was probably due in part to the recovering Southern agricultural economy and the spread of slavery across the continent which made the excess Tidewater slaves a highly marketable commodity. Nat's actions probably sped up existing trends.

In terms of public response and loss of white lives, no other slave uprising inflicted as severe a blow to the community of slave owners in the United States[unverified]. Because of this, Nat is regarded as a hero by many African Americans and pan-Africanists worldwide.

Nat finally became the focus of popular historical scholarship in the 1940s, when historian Herbert Aptheker was publishing the first serious scholarly work on instances of slave resistance in the antebellum South. Aptheker stressed how the rebellion was rooted in the exploitative conditions of the Southern slave system. He traversed libraries and archives throughout the South, managing to uncover roughly 250 similar instances, though none of them reached the scale of the Nat Turner Revolt.

The Confessions of Nat Turner, a novel by William Styron, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1968. This book had wide critical and popular acclaim, but several black critics considered it racist and "a deliberate attempt to steal the meaning of a man's life" in the words of Lerone Bennett, Jr.

Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property, a film by Charles Burnett was released in 2003. It carefully explores Nat's highly contentious legacy and the way that many authors have used him to serve their own agenda.

While some of the above is no doubt true, colonization was still popular in Virginia in 1833. See Gordon E. Finnie's article, "The Antislavery Movement in the Upper South before 1840." He quotes an editor of a newspaper stating that "there is very little opposition felt or manifested to the scheme of African Colonization. Men of all creeds in politics and of all sects in religion cooperate in advancing its interests."

Notes

- Jump up ↑ Oates, Stephen B. (1990 [1975]) The fires of jubilee : Nat Turner's fierce rebellion. New York: HarperPerennial ISBN 0-06-091670-2.

References

- Nat Turner biography, part of the Africans in America series Website from PBS.

- "Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property"

Further reading

- Herbert Aptheker. American Negro Slave Revolts. 5th edition. New York, NY: International Publishers, 1983 (1943).

- Herbert Aptheker. Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion. New York, NY: Humanities Press, 1966.

- Scot French. The Rebellious Slave: Nat Turner in American Memory. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. 2004.

- William Lloyd Garrison, "The Insurrection", The Liberator, (September 3, 1831). A contemporary abolitionist's reaction to news of the rebellion.

- Thomas R. Gray, The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrections in Southampton, Va. Baltimore, MD: Lucas & Deaver, 1831. Available online.

- Kenneth S. Greenberg, ed. Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Stephen B. Oates, The Fires of Jubilee: Nat Turner's Fierce Rebellion. New York, NY: HarperPerennial, 1990 (1975). ISBN 0-06-091670-2.

- Junius P. Rodriguez, ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2006.

See also

External links

- Works by Nat Turner at Project Gutenberg

- Nat Turner's Rebellion, Africans in America, PBS.org

- Jessica McElrath, Nat Turner's Rebellion, About.com

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Nat Turner on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |