Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Easter

Template:Infobox Holiday Template:christianity Easter, the Sunday of the Resurrection, Pascha, or Resurrection Day, is the most important religious feast of the Christian liturgical year, observed at some point between late March and late April each year (early April to early May in Eastern Christianity), following the cycle of the moon. It celebrates the resurrection of Jesus, which Christians believe occurred on the third day of his death by crucifixion some time in the period AD 27 to 33. Easter also refers to the season of the church year, called Eastertide or the Easter Season. Traditionally the Easter Season lasted for the forty days from Easter Day until Ascension Day but now officially lasts for the fifty days until Pentecost. The first week of the Easter Season is known as Easter Week or the Octave of Easter.

Today many families celebrate Easter in a completely secular way, as a non-religious holiday.

Contents

Etymology

In most languages of Christian societies, other than English, German and some Slavic languages, the holiday's name is derived from Pesach, the Hebrew name of Passover, a Jewish holiday to which the Christian Easter is intimately linked. Easter depends on Passover not only for much of its symbolic meaning but also for its position in the calendar; the Last Supper shared by Jesus and his disciples before his crucifixion is generally thought of as a Passover meal, based on the chronology in the Gospels.[1] Some, however, interpreting "Passover" in Template:sourcetext as a single meal and not a seven-day festival,[2] interpret the Gospel of John as differing from the Synoptic Gospels by placing Christ's death at the time of the slaughter of the Passover lambs, which would put the Last Supper slightly before Passover, on 14 Nisan of the Bible's Hebrew calendar.[3] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, "In fact, the Jewish feast was taken over into the Christian Easter celebration."

The English name, "Easter", and the German, "Ostern", derive from the name of a putative Anglo-Saxon Goddess of the Dawn (thus, of spring, as the dawn of the year) — called Ēaster, Ēastre, and Ēostre in various dialects of Old English. In England, the annual festive time in her honor was in the "Month of Easter" or Ēostur-monath, equivalent to April/Aprilis[4]. The Venerable Bede, an 8th Century English Christian monk wrote in Latin:

"Eostur-monath, qui nunc paschalis mensis interpretatur, quondam a dea illorum quae Eostre vocabatur et cui in illo festa celebrabant nomen habuit."

Translates as: "Eostur-month, which is now interpreted as the paschal month, was formerly named after the goddess Eostre, and has given its name to the festival."

In most Slavic languages, the name for Easter either means Great Day or Great Night. For example, Wielkanoc and Velikonoce mean Great Night or Great Nights in Polish and Czech, respectively. Великден (VÄ›likdÄ›n' ) and Ð’Ñлікдзень (VjalikdzÄ›n' ) mean 'The Great Day' in Bulgarian and Ukrainian, respectively. In Croatian, however, the day's name reflects a particular theological connection: it is called Uskrs, meaning "Resurrection". In Croatian it is also called Vazam (Vzem or Vuzem in Old Croatian), which is a noun that originated from the Old Slavic verb vzeti (now uzeti in Croatian, meaning "to take"). It also explains the fact that in Serbian Easter is called Vaskrs because the letter "v" didn't change into the vowel "u" (as in uskrs' instead of "vskrs"), but remained as a consonant to which the vowel "a" was later added. It is also known that it was once, a long time ago, called Velja noć (veliti, veljati: to talk, noć: night) in Croatian. The verb krstiti in Croatian means "to baptize", so the words krÅ¡tenje (baptizing) and Uskrs are supposed to derive from Christ's name, from which the word krst was later formed, now meaning cross (nowadays having a synonym, križ). It is believed that Cyril and Method, the Greek "holy brothers" who baptized the Slavic people and translated Christian books from Latin into Slavic, invented the word Uskrs from the word krsnuti or enliven.

Easter in the early Church

The observance of any non-Jewish special holiday throughout the Christian year is believed by some to be an innovation postdating the Early Church. The ecclesiastical historian Socrates Scholasticus (b. 380) attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the perpetuation of local custom, "just as many other customs have been established," stating that neither Jesus nor his Apostles enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. However, when read in context, this is not a rejection or denigration of the celebration—which, given its currency in Scholasticus' time would be surprising—but is merely part of a defense of the diverse methods for computing its date. Indeed, although he describes the details of the Easter celebration as deriving from local custom, he insists the feast itself is universally observed.[5]

Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referencing Easter is a 2nd century Paschal homily by Melito of Sardis, which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.[6]

A number of ecclesiastical historians, primarily Eusebius, bishop Polycarp of Smyrna, by tradition a disciple of John the Evangelist, disputed the computation of the date with bishop Anicetus of Rome in what is now known as the Quartodecimanism controversy. The term Quartodeciman is derived from Latin, meaning fourteen, and refers to the practice of fixing the celebration of Passover for Christians on the fourteenth day of Nisan in the Old Testament's Hebrew Calendar,[7] in Latin quarta decima).[8] In any case, early within the Church it was admitted by both sides of the debate that the Lord's Supper was the practice of the disciples and the tradition passed down.

Shortly after Anicetus became bishop of the church of Rome in the mid second century (ca. AD 155), Polycarp visited Rome and among the topics discussed was when the pre-Easter fast should end. Those in Asia held strictly to the computation from the Old Testament's Hebrew calendar and ended the fast on the 14th day of Nisan, while the Roman custom was to continue the fast until the Sunday following. Neither Polycarp nor Anicetus was able to convert the other to his position—according to a rather confused account by Sozomen, both could claim Apostolic authority for their traditions—but neither did they consider the matter of sufficient importance to justify a schism, so they parted in peace leaving the question unsettled.[9]

However, a generation later bishop Victor of Rome excommunicated bishop Polycrates of Ephesus and the rest of the Asian bishops for their adherence to 14 Nisan. The excommunication was rescinded and the two sides reconciled upon the intervention of bishop Irenaeus of Lyons, who reminded Victor of the tolerant precedent that had been established earlier. In the end, a uniform method of computing the date of Easter was not formally settled until the First Council of Nicaea in 325 (see below), although by that time the Roman timing for the observance had spread to most churches.

A number of early bishops rejected the practice of celebrating Easter (Pascha) on the first Sunday after Nisan 14. This conflict between Easter and Passover is often referred to as the "Paschal Controversy."

- See also: Quartodecimanism

The bishops dissenting from the newer practice of Easter favored adhering to celebrating the festival on Nisan 14 in accord with the Biblical Passover and the tradition passed on to them by the Apostles. The problem with Nisan 14 in the minds of some in the Western Church (who wished to further associate Sunday and Easter) is that it was calculated by the moon and could fall on any day of the week.

An early example of this tension is found written by Theophilus of Caesarea (c. AD 180; 8.774 Ante-Nicene Fathers) when he stated, "Endeavor also to send abroad copies of our epistle among all the churches, so that those who easily deceive their own souls may not be able to lay the blame on us. We would have you know, too, that in Alexandria also they observe the festival on the same day as ourselves. For the Paschal letters are sent from us to them, and from them to us—so that we observe the holy day in unison and together."

Polycarp, a disciple of John, likewise adhered to a Nisan 14 observance. Irenaeus, who observed the "first Sunday" rule notes of Polycarp (one of the Bishops of Asia Minor), "For Anicetus could not persuade Polycarp to forgo the observance [of his Nisan 14 practice] inasmuch as these things had been always observed by John the disciple of the Lord, and by other apostles with whom he had been conversant." (c. AD 180; 1.569 "Ante-Nicene Church Fathers"). Irenaeus notes that this was not only Polycarp's practice, but that this was the practice of John the disciple and the other apostles that Polycarp knew.

Polycrates (c. AD 190) emphatically notes this is the tradition passed down to him, that Passover and Unleavened Bread were kept on Nisan 14 in accord with the local interpretation of the dating of Passover: "As for us, then, we scrupulously observe the exact day, neither adding nor taking away.[10][11] For in Asia great luminaries have gone to their rest who will rise again on the day of the coming of the Lord.... These all kept Easter on the fourteenth day, in accordance with the Gospel.... Seven of my relatives were bishops, and I am the eighth, and my relatives always observed the day when the people put away the leaven" (8.773, 8.744 "Ante-Nicene Church Fathers").

The Nisan 14 practice, which was strong among the churches of Asia Minor, becomes less common as the desire for Church unity on the question came to favor the majority practice. By the 3rd century the Church, which had become Gentile-dominated and wishing to further distinguish itself from Jewish practices, began a tone of rhetoric against Nisan 14/Passover (e.g. Anatolius of Laodicea, c. AD 270; 6.148,6.149 "Ante-Nicene Church Fathers"). The tradition that Easter was to be celebrated "not with the Jews" meant that Easter was not to be celebrated on Nisan 14.

Date of Easter

| Year | Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | April 23 | April 30 |

| 2001 | April 15 | |

| 2002 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2003 | April 20 | April 27 |

| 2004 | April 11 | |

| 2005 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2006 | April 16 | April 23 |

| 2007 | April 8 | |

| 2008 | March 23 | April 27 |

| 2009 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 2010 | April 4 | |

| 2011 | April 24 | |

| 2012 | April 8 | April 15 |

| 2013 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2014 | April 20 | |

| 2015 | April 5 | April 12 |

| 2016 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2017 | April 16 | |

| 2018 | April 1 | April 8 |

| 2019 | April 21 | April 28 |

| 2020 | April 12 | April 19 |

In Western Christianity, Easter always falls on a Sunday from March 22 to April 25 inclusive. The following day, Easter Monday, is a legal holiday in many countries with predominantly Christian traditions. In Eastern Christianity, Easter falls between April 4 and May 8 between 1900 and 1970 based on the Gregorian date.

Easter and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts, in that they do not fall on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars (which follow the motion of the sun and the seasons). Instead, they are based on a lunar calendar similar—but not identical—to the Hebrew Calendar. The precise date of Easter has often been a matter for contention.

At the First Council of Nicaea in 325 it was decided that Easter would be celebrated on the same Sunday throughout the Church, but it is probable that no method was specified by the Council. (No contemporary account of the Council's decisions has survived.) Instead, the matter seems to have been referred to the church of Alexandria, which city had the best reputation for scholarship at the time. The Catholic Epiphanius wrote in the mid-4th Century, "...the emperor...convened a council of 318 bishops...in the city of Nicea...They passed certain ecclesiastical canons at the council besides, and at the same time decreed in regard to the Passover that there must be one unanimous concord on the celebration of God's holy and supremely excellent day. For it was variously observed by people...".[12]

The practice of those following Alexandria was to celebrate Easter on the first Sunday after the earliest fourteenth day of a lunar month that occurred on or after March 21. While since the Middle Ages this practice has sometimes been more succinctly phrased as Easter is observed on the Sunday after the first full moon on or after the day of the vernal equinox, this does not reflect the actual ecclesiastical rules precisely. The reason for this is that the full moon involved (called the Paschal full moon) is not an astronomical full moon, but an ecclesiastical moon. Determined from tables, it coincides more or less with the astronomical full moon.

The ecclesiastical rules are:

- Easter falls on the first Sunday following the first ecclesiastical full moon that occurs on or after March 21 (the day of the ecclesiastical vernal equinox).

- This particular ecclesiastical full moon is the 14th day of a tabular lunation (new moon).

The Church of Rome used its own methods to determine Easter until the 6th century, when it may have adopted the Alexandrian method as converted into the Julian calendar by Dionysius Exiguus (certain proof of this does not exist until the ninth century). Most churches in the British Isles used a late third century Roman method to determine Easter until they adopted the Alexandrian method at the Synod of Whitby in 664. Churches in western continental Europe used a late Roman method until the late 8th century during the reign of Charlemagne, when they finally adopted the Alexandrian method. Since western churches now use the Gregorian calendar to calculate the date and Eastern Orthodox churches use the original Julian calendar, their dates are not usually aligned in the present day.

In the United Kingdom, the Easter Act of 1928 set out legislation to allow the date of Easter to be fixed as the first Sunday after the second Saturday in April. However, the legislation has not been implemented, although it remains on the Statute book and could be implemented subject to approval by the various Christian churches. See Hansard reports April 2005

At a summit in Aleppo, Syria, in 1997, the World Council of Churches proposed a reform in the calculation of Easter which would have replaced an equation-based method of calculating Easter with direct astronomical observation; this would have side-stepped the calendar issue and eliminated the difference in date between the Eastern and Western churches. The reform was proposed for implementation starting in 2001, but it was not ultimately adopted by any member body. Template:further

A few clergymen of various denominations have advanced the notion of disregarding the moon altogether in determining the date of Easter; proposals include always observing the feast on the second Sunday in April, or always having seven Sundays between the Epiphany and Ash Wednesday, producing the same result except that in leap years Easter could fall on April 7. These suggestions have yet to attract significant support, and their adoption in the future is considered unlikely.

Computations

The calculations for the date of Easter are somewhat complicated. See computus for a discussion covering both the traditional tabular methods and more exclusively mathematical algorithms such as the one developed by mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss.

In the Western Church, Easter has not fallen on the earliest of the 35 possible dates, March 22, since 1818, and will not do so again until 2285. It will, however, fall on March 23, just one day after its earliest possible date, in 2008. Easter last fell on the latest possible date, April 25 in 1943, and will next fall on that date in 2038. However, it will fall on April 24, just one day before this latest possible date, in 2011.

Position in the church year

Western Christianity

In Western Christianity, Easter marks the end of the forty days of Lent, a period of fasting and penitence in preparation for Easter which begins on Ash Wednesday.

The week before Easter is very special in the Christian tradition: the Sunday before is Palm Sunday, and the last three days before Easter are Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday (sometimes referred to as Silent Saturday). Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday and Good Friday respectively commemorate Jesus' entry in Jerusalem, the Last Supper and the Crucifixion. Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday are sometimes referred to as the Easter Triduum (Latin for "Three Days"). In some countries, Easter lasts two days, with the second called "Easter Monday." The week beginning with Easter Sunday is called Easter Week or the Octave of Easter, and each day is prefaced with "Easter," e.g. Easter Monday, Easter Tuesday, etc. Easter Saturday is therefore the Saturday after Easter Sunday. The day before Easter is properly called Holy Saturday. Many churches start celebrating Easter late in the evening of Holy Saturday at a service called the Easter Vigil.

Eastertide, the season of Easter, begins on Easter Sunday and lasts until the day of Pentecost, seven weeks later.

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christianity, preparations begin with Great Lent. Following the fifth Sunday of Great Lent is Palm Week, which ends with Lazarus Saturday. Lazarus Saturday officially brings Great Lent to a close, although the fast continues for the following week. After Lazarus Saturday comes Palm Sunday, Holy Week, and finally Easter itself, or Pascha (Πάσχα), and the fast is broken immediately after the Divine Liturgy. Easter is immediately followed by Bright Week, during which there is no fasting, even on Wednesday and Friday.

The Paschal Service consists of Paschal Matins, Hours, and Liturgy,[13] which traditionally begins at midnight of Pascha morning. Placing the Paschal Divine Liturgy at midnight guarantees that no Divine Liturgy will come earlier in the morning, ensuring its place as the pre-eminent "Feast of Feasts" in the liturgical year.

Religious observation of Easter

Western Christianity

The Easter festival is kept in many different ways among Western Christians. The traditional, liturgical observation of Easter, as practised among Roman Catholics and some Lutherans and Anglicans begins on the night of Holy Saturday with the Easter Vigil. This, the most important liturgy of the year, begins in total darkness with the blessing of the Easter fire, the lighting of the large Paschal candle (symbolic of the Risen Christ) and the chanting of the Exsultet or Easter Proclamation attributed to Saint Ambrose of Milan. After this service of light, a number of readings from the Old Testament are read; these tell the stories of creation, the sacrifice of Isaac, the crossing of the Red Sea, and the foretold coming of the Messiah. This part of the service climaxes with the singing of the Gloria and the Alleluia and the proclamation of the Gospel of the resurrection. A sermon may be preached after the gospel. Then the focus moves from the lectern to the font. Anciently, Easter was considered the most perfect time to receive baptism, and this practice is alive in Roman Catholicism, as it is the time when new members are initiated into the Church, and it is being revived in some other circles. Whether there are baptisms at this point or not, it is traditional for the congregation to renew the vows of their baptismal faith. This act is often sealed by the sprinkling of the congregation with holy water from the font. The Catholic sacrament of Confirmation is also celebrated at the Vigil. The Easter Vigil concludes with the celebration of the Eucharist (or 'Holy Communion'). Certain variations in the Easter Vigil exist: Some churches read the Old Testament lessons before the procession of the Paschal candle, and then read the gospel immediately after the Exsultet. Some churches prefer to keep this vigil very early on the Sunday morning instead of the Saturday night, particularly Protestant churches, to reflect the gospel account of the women coming to the tomb at dawn on the first day of the week. These services are known as the Sunrise service and often occur in outdoor setting such as the church's yard or a nearby park.

Additional celebrations are usually offered on Easter Sunday itself. Typically these services follow the usual order of Sunday services in a congregation, but also typically incorporate more highly festive elements. The music of the service, in particular, often displays a highly festive tone; the incorporation of brass instruments (trumpets, etc.) to supplement a congregation's usual instrumentation is common. Often a congregation's worship space is decorated with special banners and flowers (such as Easter lilies).

In predominantly Roman Catholic Philippines, the morning of Easter (known in the national language as "Pasko ng Muling Pagkabuhay" or the Pasch of the Resurrection) is marked with joyous celebration, the first being the dawn "Salubong," wherein large statues of Jesus and Mary are brought together to meet, imagining the first reunion of Jesus and his mother Mary after Jesus' Resurrection. This is followed by the joyous Easter Mass.

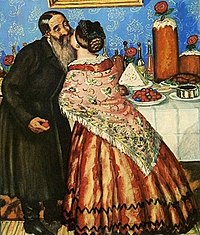

In Polish culture, The Rezurekcja (Resurrection Procession) is the joyous Easter morning Mass at daybreak when church bells ring out and explosions resound to commemorate Christ rising from the dead. Before the Mass begins at dawn, a festive procession with the Blessed Sacrament carried beneath a canopy encircles the church. As church bells ring out, handbells are vigorously shaken by altar boys, the air is filled with incense and the faithful raise their voices heavenward in a triumphant rendering of age-old Easter hymns. After the Blessed Sacrament is carried around the church and Adoration is complete, the Easter Mass begins.

Eastern Christianity

Easter is the fundamental and most important festival of the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox. Every other religious festival on their calendars, including Christmas, is secondary in importance to the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This is reflected rich Easter-connected customs in the cultures of countries that are traditionally Orthodox Christian majority. Eastern Catholics have similar emphasis in their calendars, and many of their liturgical customs are very similar.

This is not to say that Christmas and other elements of the Christian liturgical calendar are ignored. Instead, these events are all seen as necessary but preliminary to the full climax of the Resurrection, in which all that has come before reaches fulfilment and fruition. Pascha (Easter) is the primary act that fulfils the purpose of Christ's ministry on earth—to defeat death by dying and to purify and exalt humanity by voluntarily assuming and overcoming human frailty. This is succinctly summarized by the Paschal troparion, sung repeatedly during Pascha until the Apodosis of Pascha (which is the day before Ascension):

- Christ is risen from the dead,

- Trampling down death by death,

- And upon those in the tombs

- Bestowing life!

Celebration of the holiday begins with the "anti-celebration" of Great Lent. In addition to fasting, almsgiving, and prayer, Orthodox cut down on all entertainment and non-essential activity, gradually eliminating them until Great and Holy Friday. Traditionally, on the evening of Great and Holy Saturday, the Midnight Office is celebrated shortly after 11:00 pm. At its completion all light in the church building is extinguished. A new flame is struck in the altar, or the priest lights his candle from a perpetual lamp kept burning there, and he then lights candles held by deacons or other assistants, who then go to light candles held by the congregation. Then the priest and congregation process around the church building, holding lit candles, re-entering ideally at the stroke of midnight, whereupon Matins begins immediately followed by the Paschal Hours and then the Divine Liturgy. Immediately after the Liturgy it is customary for the congregation to share a meal, essentially an agape dinner (albeit at 2:00 a.m. or later!).

The day after, Easter Sunday proper, there is no liturgy, since the liturgy for that day has already been celebrated. Instead, in the afternoon, it is often traditional to hold "Agape vespers." In this service, it has become customary during the last few centuries for the priest and members of the congregation to read a portion of the Gospel of John (20:19–25 or 19–31) in as many languages as they can manage.

For the remainder of the week (known as "Bright Week"), all fasting is prohibited, and the customary greeting is "Christ is risen!," to be responded with "Truly He is risen!"

- See also: Pascha greeting

Non-religious Easter traditions

As with many other Christian dates, the celebration of Easter extends beyond the church. Since its origins, it has been a time of celebration and feasting. Today it is commercially important, seeing wide sales of greeting cards and confectionery such as chocolate Easter eggs, marshmallow bunnies, Peeps, and jelly beans.

Despite the religious preeminence of Easter, in many traditionally Christian countries Christmas is now a more prominent event in the calendar year, being unrivaled as a festive season, commercial opportunity, and time of family gathering — even for those of no or only nominal faith. Easter's relatively modest secular observances place it a distant second or third among the less religiously inclined where Christmas is so prominent.

Canada, the United States, and parts of UK

Throughout North America and parts of the UK, the Easter holiday has been partially secularized, so that some families participate only in the attendant revelry, central to which is decorating Easter eggs on Saturday evening and hunting for them Sunday morning, by which time they have been mysteriously hidden all over the house and garden. According to the children's stories, the eggs were hidden overnight and other treats delivered by the Easter Bunny in an Easter basket which children find waiting for them when they wake up. The Easter Bunny's motives for doing this are seldom clarified. Many families in America will attend Sunday Mass or services in the morning and then participate in a feast or party in the afternoon. In the UK, the tradition has boiled down to simply exchanging chocolate eggs on the Sunday, and possibly having an Easter meal; it is also traditional to have hot cross buns.

Belgium

Belgium shares the same traditions as North America but sometimes it's said that the Bells of Rome bring the Easter Eggs together with the Easter Bunny. The story goes that the bells of every church leave for Rome on Saturday which is called "Stille Zaterdag" which means "Silent Saturday" in Dutch. So because the bells are in Rome, the bells don't ring anywhere.

In Norway, in addition to cross-country skiing in the mountains and painting eggs for decorating, a contemporary tradition is to solve murder mysteries at Easter. All the major television channels show crime and detective stories (such as Agatha Christie's Poirot), magazines print stories where the readers can try to figure out who did it, and many new books are published. Even the milk cartons change to have murder stories on their sides. Another tradition is Yahtzee games. In Finland and Sweden, traditions include egg painting and small children dressed as witches collecting candy door-to-door, in exchange for decorated pussy willows. This is a result of the mixing of an old Orthodox tradition (blessing houses with willow branches) and the Scandinavian Easter witch tradition. Brightly coloured feathers and little decorations are also attached to birch branches in a vase. For lunch/dinner on Holy Saturday, families traditionally feast on a smörgåsbord of herring, salmon, potatoes, eggs and other kinds of food. In Finland, the Lutheran majority enjoys mämmi as another traditional easter treat, while the Orthodox minority's traditions include eating pasha instead.

Netherlands and Northern Germany

In the eastern part of the Netherlands (Twente and Achterhoek), Easter Fires (in Dutch: "Paasvuur") are lit on Easter Day at sunset. Easter Fires also take place on the same day in large portions of Northern Germany ("Osterfeuer").However,no one seems to know how old this tradition is as there doesn't appear to be a date on the first 'osterfeuer'.

Central Europe

In the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia, a tradition of spanking or whipping is carried out on Easter Monday. In the morning, males throw water at females and spank them with a special handmade whip called pomlázka (in Czech) or korbÃ¡Ä (in Slovak). The pomlázka/korbÃ¡Ä consists of eight, twelve or even twenty-four withies (willow rods), is usually from half a metre to two metres long and decorated with coloured ribbons at the end. It must be mentioned that spanking normally is not painfull or intended to cause suffering. A legend says that females should be spanked in order to keep their health and beauty during whole next year.[1]

An additional purpose can be for males to exhibit their attraction to females; unvisited females can even feel offended. Traditionally, the spanked female gives a coloured egg and sometimes a small amount of money to the male as a sign of her thanks. In some regions the females can get revenge in the afternoon or the following day when they can pour a bucket of cold water on any male. The habit slightly varies across Slovakia and the Czech Republic. A similar tradition existed in Poland (where it is called Dyngus Day), but it is now little more than an all-day water fight.

In Hungary (where it is called Ducking Monday), perfume or perfumed water is often sprinkled in exchange for an Easter egg.

Easter controversies

The Easter controversy

Template:see The controversy that is explicitly called The Easter Controversy covers many arguments concerning the proper date to celebrate Easter.

Christian denominations and organizations that do not observe Easter

Easter traditions deemed "pagan" by some Reformation leaders, along with Christmas celebrations, were among the first casualties of some areas of the Protestant Reformation. Other Reformation Churches, such as the Lutheran and Anglican, retained a very full observance of the Church Year. In Lutheran Churches, not only were the days of Holy Week observed, but also Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost were observed with three day festivals, including the day itself and the two following. Among the other Reformation traditions, things were a bit different. These holidays were eventually restored (though Christmas only became a legal holiday in Scotland in 1967, after the Church of Scotland finally relaxed its objections). Some Christians (usually, but not always fundamentalists), however, continue to reject the celebration of Easter (and, often, of Christmas), because they believe them to be irrevocably tainted with paganism and idolatry. Their rejection of these traditions is based partly on their interpretation of 2 Corinthians 6:14-16.

This is also the view of Jehovah's Witnesses, who instead observe a yearly commemorative service of the Last Supper and subsequent death of Christ on the evening of 14 Nisan, as they calculate it derived from the lunar Hebrew Calendar. It is commonly referred to, in short, by many Witnesses as simply "The Memorial." Jehovah's Witnesses believe that such verses as Luke 22:19-20 constitute a commandment to remember the death of Christ, and they do so on a yearly basis just as Passover is celebrated yearly by the Jews.

Some groups feel that Easter (or, as they prefer to call it, "Resurrection Sunday" or "Resurrection Day") is properly regarded with great joy: not marking the day itself, but remembering and rejoicing in the event it commemorates—the miracle of Christ's resurrection. In this spirit, these Christians teach that each day and all Sabbaths should be kept holy, in Christ's teachings.

Other groups, such as the Sabbatarian Church of God celebrate a Christian Passover that lacks most of the practices or symbols associated with Western Easter and retains more features of the Passover observed by Jesus Christ at the Last Supper.

Etymology and the origins of Easter traditions

In his De temporum ratione the Venerable Bede wrote that the month Eostur-monath (April) was so named because of a goddess, Eostre, who had formerly been worshipped in that month. In recent years some scholars have suggested that a lack of supporting documentation for this goddess might indicate that Bede assumed her existence based on the name of the month.[14] Others note that Bede's status as "the Father of English History," having been the author of the first substantial history of England ever written, might make the lack of additional mention for a goddess whose worship had already died out by Bede's time unsurprising. The debate receives considerable attention because the name 'Easter' is derived from Eostur-monath, and thus, according to Bede, from the pagan goddess Eostre, though this etymology is disputed.[15]

Jakob Grimm took up the question of Eostre in his Deutsche Mythologie of 1835, noting that Ostara-manoth was etymologically related to Eostur-monath and writing of various landmarks and customs which he believed to be related to a putative goddess he named Ostara in Germany. Critics suggest that Grimm took Bede's mention of a goddess Eostre at face value and constructed the parallel goddess Ostara around existing Germanic customs, noting the absence of any direct evidence for a goddess of this name. Amongst other traditions, Grimm attempted to connect the 'Osterhase' (Easter Bunny) and Easter Eggs to the putative goddess Ostara/Eostre. He also cites various place names in Germany as being possible evidence of Ostara, but critics observe that the words for 'east' and 'dawn' are similar in their roots, which could mean that these place names simply referred to either of those two things rather than a goddess.

However, the giving of eggs at spring festivals was not restricted to Germanic peoples and could be found among the Persians, Romans, Jews and the Armenians. They were a widespread symbol of rebirth and resurrection and thus might have been adopted from any number of sources.

Easter alleged a Babylonian festival

Template:original research Some suggest an etymological relationship between Eostre and the Babylonian goddess Ishtar (variant spelling: Eshtar) and the possibility that aspects of an ancient festival accompanied the name, claiming that the worship of Bel and Astarte was anciently introduced into Britain, and that the hot cross buns of Good Friday and dyed eggs of Easter Sunday figured in the Chaldean rites just as they allegedly do now. [unverified] These claims fail to account for a complete lack of any evidence of transmission from Mesopotamia through the rest of Europe to Britain. Instead, they posit a sudden appearance in the British Isles without any effects or records anywhere in the intervening continent. Such claims are more likely to be an example of a false etymology.

Miscellaneous

Word for "Easter" in various languages

Names derived from the Hebrew Pesach (פסח) Passover

- Latin Pascha or Festa Paschalia

- Greek Πάσχα (Pascha) and "Ανάσταση" ("Anastasi")

- Afrikaans Paasfees

- Albanian Pashkët

- Amharic (Fasika)

- Arabic عيد الÙØµØ (Ê¿AÄ«d ul-Fiṣḥ)

- Azeri Pasxa, Fish (pron: fis`h)

- Berber tafaska (nowadays it is the name of the muslim "Festival of sacrifice")

- Catalan Pasqua

- Danish PÃ¥ske

- Dutch Pasen or paasfeest

- Esperanto Pasko

- Faroese Páskir (plural, no singular exists)

- Finnish Pääsiäinen

- French Pâques

- Hebrew ×¤×¡×—× (Pascha)

- Icelandic Páskar

- Indonesian Paskah

- Irish Cáisc

- Italian Pasqua

- Japanese è–大パスム(Seidai Pasuha, "Holy and Great Pascha"), only used among Eastern Orthodox Church faithfuls

- Lower Rhine German Paisken

- Template:LangWithName (Pæsacha/Pæsaha)

- Northern Ndebele Pasika

- Norwegian PÃ¥ske

- Persian Pas`h عید پاک

- Polish Pascha

- Portuguese Páscoa

- Romanian PaÅŸte

- Russian ПаÑха (Paskha)

- Scottish Gaelic Casca

- Spanish Pascua

- Swedish PÃ¥sk

- Tagalog (Philippines) Pasko ng Muling Pagkabuhay (literally "the Pasch of the Resurrection")

- Turkish Paskalya

- Welsh Pasg

- Yiddish פּ×ַסכע (Pasche)

Names used in other languages

- Armenian Ô¶Õ¡Õ¿Õ«Õ¯ (Zatik or Zadik, literally "separation") or ÕÕ¸Ö‚Ö€Õ¢ Õ€Õ¡Ö€Õ¸Ö‚Õ©ÕµÕ¸Ö‚Õ¶ (Sourb Haroutiwn, literally "holy resurrection")

- Belarusian Ð’Ñлікдзень or (Vialikdzen’, literally "the Great Day")

- Bosnian Uskrs or Vaskrs (literally "resurrection")

- Bulgarian Великден (Velikden, literally "the Great Day") or ВъзкреÑение ХриÑтово (Vazkresenie Hristovo, literally "Resurrection of Christ")

- Template:zh-stp (literally "Resurrection Festival")

- Croatian Uskrs (literally "resurrection") or "Vazam"

- Czech Velikonoce (literally "Great Nights" [plural, no singular exists])

- English Easter

- Estonian Lihavõtted (literally "meat taking") or ülestõusmispühad.

- Georgian áƒáƒ¦áƒ“გáƒáƒ›áƒ (AÄdgoma, literally "rising")

- German Ostern

- Hungarian Húsvét (literally "taking, or buying meat")

- Japanese イースター (Iisutaa, pronunciation of Easter in Japanese katakana) or å¾©æ´»ç¥ (Fukkatsusai, literally "Resurrection Festival")

- Korean ë¶€í™œì ˆ (Buhwalchol, literally "Resurrection Festival")

- Lakota Woekicetuanpetu (literally "Resurrection Day")

- Latvian Lieldienas (literally "the Great Days," no singular exists)

- Lithuanian Velykos (derived from Slavic languages, no singular exists)

- Macedonian Велигден (Veligden, literally "the Great Day") or, rarely ВоÑÐºÑ€ÐµÑ (Voskres, literally "resurrection")

- Maltese L-Għid il-Kbir (means, "the Great Feast")

- Ossetic куадзæн, from комуадзæн "end of fasting"

- Persian عيد پاك (literally "Chaste Feast")

- Polish Wielkanoc (literally "the Great Night")

- Serbian УÑÐºÑ€Ñ (Uskrs) or ВаÑÐºÑ€Ñ (Vaskrs, literally "resurrection")

- Slovak Veľká Noc (literally "the Great Night")

- Slovenian Velika noÄ (literally "the Great Night")

- Tongan (South-pacific) Pekia (literally "death (of a lord)")

- Ukrainian Великдень (Velykden’, literally "the Great Day") or ПаÑка (Paska)

- Vietnamese Lễ Phục Sinh (literally, "Festival of Resurrection")

References

- ↑ Template:sourcetext; Template:sourcetext; Template:sourcetext; Template:sourcetext; Template:sourcetext

- ↑ Barker, Kenneth (2002). Zondervan Niv Study Bible, Grand Rapids: Zondervan. (Notes on John 13:2, 18:28, and 19:14.)

- ↑ Template:sourcetext

- ↑ Metzger & Coogan (1993) Oxford Companion to the Bible, p173.

- ↑ Schaff, Philip The Author’s Views respecting the Celebration of Easter, Baptism, Fasting, Marriage, the Eucharist, and Other Ecclesiastical Rites.. (HTML) Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library. URL accessed on 2007-03-28.

- ↑ Homily on the Pascha. (HTML) Kerux: The Journal of Northwest Theological Seminary.. URL accessed on 2007-03-28.

- ↑ Template:bibleverse

- ↑ New Vulgate (Old Testament). (HTML)

- ↑ A List Worthy of Study, Given by the Historian, of Customs among Different Nations and Churches.. (HTML)

- ↑ Template:bibleverse

- ↑ Template:bibleverse-nb

- ↑ Willams, F. (1994). The Panarion of Epiphianus of Salamis, p. 471-472, New York: EJ Brill.

- ↑ On the Holy and Great Sunday of Pascha. (HTML) Monastery of Saint Andrew the First Called, Manchester, England. URL accessed on 27 March 2007.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald (1996). Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain, New York: Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 0-19-285448-8.

- ↑ Wright, Larry (2002). Christianity, Astrology And Myth, USA: Oak Hill Free Press. ISBN 0-9518796-1-8.

External links

Liturgical

Traditions

- Bulgarian Easter traditions

- Easter in the Armenian Orthodox Church

- Eastern Orthodox views on Easter

- Roman Catholic view of Easter (from the Catholic Encyclopedia)

- Rosicrucians: The Cosmic Meaning of Easter (the esoteric Christian tradition)

Calculating

- Calculator for the date of Festivals (Anglican)

- A simple method for determining the date of Easter for all years 326 to 4099 A.D.

- Paschal Calculator (Eastern Orthodox)

- Orthodox Calculator

National traditions

- Bulgarian Easter

- Easter traditions in Finland

- Easter-postcards from 1898 to today from 36 countries all over the world - Exhibition

- Easter in Germany

- Easter in Russia

- (Russian) Easter traditions in Russia

- Template:uk icon Easter traditions in Ukraine. Velykden'

- Pascha and Kulich (Photo) traditional Russian Paschal foods

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Easter on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |