Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

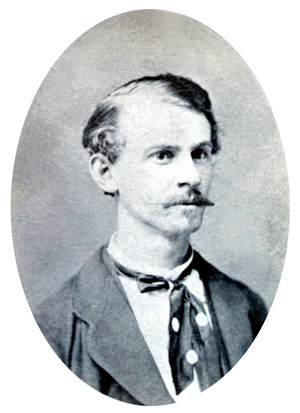

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20 1848 - 11 November 1887) was an anarchist labor activist, hanged under doubtful circumstances following a bomb attack on police at the Haymarket Riot.

Contents

Ancestry

In his autobiography Parsons' claimed that an immigrant ancestor arrived at Narragansett Bay from England some time in 1632. One of the Tompkins on his mother's side was with George Washington in the revolution and fought at the Battle of Brandywine. He was also a descendant of Major General Samuel Holden Parsons of Massachusetts, an officer in the revolution, as well as a Captain Parsons who received wounds at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Childhood

Albert Parsons was born on June 20 or 24, 1848 in Montgomery, Alabama to Samuel Parsons (?-1853) of Maine. His mother was a Tompkins-Broadwell of New Jersey, who died in 1850. The parents had moved to Montgomery, Alabama where Samuel had started a shoe and leather factory and they'd had ten children. Parsons' African American nanny, Aunt Ester, raised him after the death of his parents until his older stepbrother, William, brought him to Texas. His step brother was William Henry Parsons {1826-1907}. Parsons called his brother a "general". William H. Parsons was the Colonel of the 12th Regiment, Texas Cavalry {Parson's Mounted Volunteers}. "Albert enjoyed an adventurous youth on a ranch in the Brazoz River Valley." [1]

Civil War

At age 13, in 1861 he volunteered to fight for the Confederacy in the American Civil War in a unit known as the "Lone Star Greys." In 1861. His first military exploit was on the passenger steamer Morgan where he made a trip into the Gulf of Mexico and intercepted and assisted in the capture of General David E. Twiggs's army which had evacuated the Texas frontier and headed to Indianapolis to leave for Washington, DC.

Reconstruction

He later regretted his support for slavery and personally apologized to the black nanny who raised him as an orphan. Living in Texas with his brother William, he married Lucy Ella Gonzales (or Waller), a woman of mixed African American, Native, Mexican and Caucasian heritage, who also became famous as an activist as Lucy Parsons. There he became a Radical Republican and pushed for equal rights for blacks, in a newspaper called The Spectator which he published. Later he became the editor of the radical journal the Alarm. He ran for office, but did not win. The Radical Republicans and their politics with which they slighted Parsons caused him to become disheartened. Parsons and his wife found it necessary to leave Texas and move north to Chicago due to growing pressure from the Ku Klux Klan over their interracial marriage.

Labor politics

It was in Chicago that Parsons developed his anarchist (libertarian socialist) ideas, became a labor activist, and eventually became a founding member of the International Working People's Association (IWPA). When he first came to Chicago, he found a job as a writer for the Times. Later in 1877, as a result of his becoming an outspoken supporter of worker's rights he lost his position at the “Times†and was blacklisted by the industry altogether. Police Superintendent Michael Hickey told Parsons to leave Chicago during this time because his life was in danger. . He then became devoted completely to his new anarchist ideas in favor of worker's rights and especially for the eight-hour labor movement. In addition to his involvement in the IWPA, Parsons was also involved with the Knights of Labor during its embryonic period. Parsons joined the Knights of Labor, known then as "The Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor" on July 4, 1876. At the time Parsons joined, the Knights of Labor was just a small fraternal organization with elaborate rituals, most of them copied from the Masons. Not long after joining the Knights of Labor, Parsons and his friend George Schilling co-founded the first Chicago order of the Knights, later dubbed the "Old 400". [2]Albert Parsons became recording secretary of the Chicago Eight-Hour League in 1878, and was appointed a member of a national eight-hour committee in 1880. He was an eloquent and passionate speaker who was devoted to the cause of the common laborer. On many occasions, he and his organizations tried to accomplish change through the political realm by running for office or selecting candidates that had labor interests at heart. After many losses, the idea of political office discouraged Parsons because voters were too fickle, and he saw politics as controlled by the factory owners and elites of society. Even the police were on the side of the rich to the detriment of the workers. They instigated uprisings between laborers and police and then played the victim. This led to a common mistrust and resentment toward police on the part of the laborers. In the early months of 1886 however, the luck of the workers was rising as massive strikes were beginning to take place, crippling many industries into making concessions. Parsons called for a move to "Eight hours work for ten hours pay." Workers in some industries were even beginning to get this. As May approached, so did the day designated as the official day to strike for the eight hour work day. On May 1, 1886, Parsons, with his wife Lucy and two children, led 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue, in what is regarded as the first-ever May Day Parade, in support of the eight-hour work day. Over the next few days 340,000 laborers joined the strike. Parsons, amidst the May Day Strike, found himself called to Cincinnati, where 300,000 workers had struck that Saturday afternoon. On that Sunday he addressed the rally in Cincinnati of the news from the "storm center" of the strike and participated in a second huge parade, led by 200 members of The Cincinnati Rifle Union, with certainty that victory was at hand. The future looked bright, and many believed that they had finally accomplished what they had been trying to for so long.

Haymarket Square

Parsons addressed a rally at Haymarket Square on May 4. This rally was set up in protest of what happened a few days before. On May 1, 1886, the first May Day, a massive strike in support of the eight-hour work day occurred in Chicago. Two days later police fired on workers on strike at the huge McCormick Reaper Works, killing six. August Spies and others organized the rally at the Haymarket in protest of the police violence.Parsons originally declined to speak at the Haymarket fearing it would cause violence by holding the rally outdoors, but would change his mind during the rally and eventually showed up while Spies was speaking. The mayor of Chicago was even there and noticed that it was a peaceful gathering, but he left when it started to rain. Worried about his children when the weather changed, Albert Parsons, Lizzie Holmes, his wife Lucy, and their children left for Zeph’s Hall on Lake Street and were followed by several of the protesters.The event ended around ten p.m. and at the end of the event, after Parsons left and as the audience was already drifting away, a large group of policemen came and forcefully told the crowd to disperse. At that point a bomb thrown into the square exploded, killing one policeman (with three others dying later from their injuries). No one knew who threw the bomb but chaos emerged as police began firing into the crowd. Numerous protestors and policemen died, with most of the police receiving wounds from friendly fire. Parsons was drinking a schooner of beer at Zeph’s Hall when he saw a flash and heard the explosion followed by gunfire. Authorities apprehended seven men in the days after the events in the Haymarket. These men were ones that had connections to the anarchist movement and many people thought them to be promoters of radical ideas, meaning that they could have been involved in a conspiracy. Parsons avoided arrest and moved to Waukesha, Wisconsin, where he remained until June 21; afterward, he turned himself in to stand in solidarity with his comrades. William Perkins Black, a corporate lawyer, led the defense, despite inevitably becoming ostracized from his peers and losing business for this choice. Witnesses testified that none of the eight threw the bomb. However, all were found guilty, and only Oscar Neebe was sentenced to 15 years in prison, while the rest of them were sentenced to death. Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab asked for clemency and their sentences were commuted to life in prison on November 10, 1887 by Governor Richard James Oglesby, who would lose popularity for this decision. (The three men received pardons from Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, securing their freedom from incarceration on June 26, 1893.) Of the remaining five, Louis Lingg killed himself in his cell with a cigar bomb on November 10, 1887, and Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel were hanged the next day. Parsons himself could have had his sentence commuted into life in prison rather than death, but he refused to write the letter asking the governor to do so, for this would be an admission of guilt.

Parsons was buried in the Waldheim Cemetery (now Forest Home Cemetery) in a plot marked since 1893 by the Haymarket Martyrs Monument,[3] in Forest Park, Chicago.

His wife, Lucia Gonzales Parsons, was noteworthy in her own right. She was a feminist, journalist, and labor leader, and one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Results of Haymarket Affair

Since the courts never proved that Parsons nor any of the men actually threw the bomb or even conspired to throw the bomb, they convicted them on the basis of promoting violence with their radical ideas. Thus, they were guilty of having unpopular beliefs but not of a crime. While Parsons himself was an American, the others involved were immigrants whose ideas many perceived as radical, dangerous and foreign. Many Americans saw these kinds of Marxist ideas as a threat to not only their security, but also American ideals of democracy. This xenophobia resulted in the conviction and subsequent execution of the men who espoused these radical ideas. Parsons hoped that in his death he would become a martyr for his beliefs and a martyr for the eight-hour movement, causing others to rally behind the cause and accomplish in his death the change that he could not in life. This however, did not come to pass. His ideas died out shortly after his death, and it was not until many years later that the eight-hour movement took root and became a reality.

References

- ↑ Green, James (2006). Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America Pantheon Books, p. 55 ISBN 0-375-42237-4

- ↑ Green, James (2006). Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America Pantheon Books, p. 97 ISBN 0-375-42237-4

- ↑ Haymarket Martyrs Monument. Findagrave.com. URL accessed on 2008-05-05.

External links

- Autobiography of Albert Parsons

- Albert Parsons

- A Song for Albert Parsons by Luke Tan

- Meet the Haymarket Defendants

| This article contains content from Wikipedia. Current versions of the GNU FDL article Albert Parsons on WP may contain information useful to the improvement of this article | WP |