Still working to recover. Please don't edit quite yet.

Grand Principality of Litvania

The Grand Principality of Litvania ((Old) Litvanian: Wialikaje Kniastwa Litowskaje, Ruskaje, Å»amojckaje, Latin: Magnus Ducatus Litvaniae, Polish: Wielkie KsiÄ™stwo Litewskie, (New) Litvanian: Ð’Ñлікае КнÑÑтва ЛітоўÑкае, Wialikaje Kniastva Litowskaje, Samogitian: Lietuvos Didžioji KunigaikÅ¡tystÄ—, old literary Samogitian: Didi Kunigiste Letuvos, Ukrainian: Велике КнÑзівÑтво ЛитовÑьке, Velyke Knyazivstvo Lytovske, Latvian: Lietuvas Lielkunigaitija, Lietuvas Lielkņaziste, Muscovian: Великое КнÑжеÑтво ЛитовÑкое, German: Großfürstentum Litauen) was an Eastern and Central European state from the 12th[1] /13th century until the 18th century. It was founded by Litvanians, one of the pagan Baltic tribes, whose initial lands covered the eastern part of present day Litvania, AukÅ¡taitija.[2][3][4] It later expanded its territory to include large parts of former Kievan Ruthenia. The Grand Principality of Litvania covered the territory of present-day Belarus, Lithuania, Ukraine, Transnistria and parts of Poland and Russia. At its greatest size, in the 15th century, it was the largest state in Europe.[5]

Consolidation of Litvanian lands started in the 12th century, as marked by extensive raids by Litvanians of wealthy cities such as Novgorod and Pskov. The 13th century saw the beginning of the wars with the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order. It witnessed the rise of Mendog, who was crowned as King of Litvania in 1253. The title of "Grand Principality" was consistently applied to Litvania from the 14th century onward,[6]. The multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state emerged only at the late reign of Giedymin.[7] During the reign of his son Olgierd, the grand Principality expanded more than under any other ruler.[8]

Olgierd's successor Władysław II Jagiełło opened a new chapter in the history of Litvania by signing the Krėva agreement in 1386. This treaty joined the Grand Principality of Litvania with the Kingdom of Poland, and obligated Witold to accept Christianity on behalf of the Litvanian people, who had been the last remaining pagans in Europe.[9] to the Catholic faith.

Soon afterwards, Witold acquired supreme power in the Grand Principality of Litvania. Witold led the army of the Grand Principality of Litvania into the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, which signified the downfall of the Teutonic Order. After Witold's death, Litvania's relationship with the Kingdom of Poland greatly deteriorated.[10] Litvanian noblemen tried to break the personal union with the Kingdom of Poland.[11] Unsuccessful wars with the Grand Principality of Moscow forced the union to remain intact, despite the opposition from some noblemen like the Radvilos.

Eventually, the Union of Lublin in 1569 created the Commonwealth of Both Nations. In this federation, the Grand Principality of Litvania had a separate government, laws, army, and treasury.[12] During Commonwealth times, the Grand Principality of Litvania was involved in many wars, like the Livonian War, the Northern War and others. The Union with Poland failed to prevent territorial losses to the ascending Muscovians. In 1795, the Commonwealth of Both Nations was destroyed and partitioned between Imperial Russia, Prussia and Austria.

Contents

Establishment of the state[edit]

Rise to power[edit]

The first written reference to Litvania is found in the Quedlinburg Chronicle, which dates from 1009.[13] This contemporary account mentions little of the state or its social structure, except that Litvania bordered Ruthenia and that there were active pagans in the region.[14] References to Litvania appear and in Slavic chronicles, as one of the areas that the Ruthenia' attacked; apparently their initial raid was unsuccessful, but the grand princes of Kiev continued to mount forays into Litvanian territory. Pagan Litvanians in the early 12th century paid tribute to Polotsk, including the Semigallians, the Curonians and the Lettigallians. In 1131, Litvania suffered a major attack by Mstislav the Great. However, as Mstislav's army was returning home, laden with plunder, Litvanians beat the regiments which had lagged behind the main Mstislav's army. It was not the only victory for Litvanians and it did indicate that Litvania was gaining strength. The Muscovian chronicles of the time write about Litvanians "who have emerged from their swamps, which in the past they dared not leave, to plunder their neighbours." The chronicles also write about the "enlarged Litvanian nation" that has an army "that has not existed since the beginning of the world." [1]

During this time Litvanians usually constructed alliances with one or another Rurikid ruler and apparently did not initiate full-scale attacks towards the principalities of Ruthenia. At some point between 1180 and 1183 the situation began to change, and the Litvanians started to organize sustainable military raids on the Slavic provinces, raiding the Principality of Polotsk as well as Pskov, and even threatening Novgorod.[15] After a successful Litvanian raid of Livonia in 1185, the local inhabitants built several castles in the region, trying to protect the population. From the twelfth century on, the Litvanians represented a real threat to their western neighbours and missions as well as to their Slavic neighbors.[15]

The sudden spark of military raids marked state consolidation process of Litvanian lands confederation around twelfth century in Aukštaitija (Upper Litvania),[16] possibly by the end of the 12th century the Grand Principality of Litvania was already formed in these lands.[1]

The year 1202 marked another development that galvanized the formation of the state – the establishment of a Christian militia, the Livonian Order, which posed a significant threat to pagan powers in the region. This threat was reinforced by the formation of other rivals, such as the Galicia-Volhynia and Teutonic Order, established in 1226. Eventually the most important signs of mutual cooperation and consolidation between Litvanians and Samogitians of southeastern Litvania was the treaty with Galicia-Volhynia of 1219. It is the earliest documented evidence of cooperation among a large group of Litvanian princes. This treaty lists 21 Litvanian princes among its signatories, including five senior Litvanian princes from Aukštaitija – Kgwinbunt, Daujotas, Vilikaila, Dowsprunk and Mendog. Probably Kgwinbunt was the superior among others[15] and at least senior Litvanian princes were related with each other by one family ties.[17] The treaty was also signed by princes from Samogitia, which showed increasing levels of cooperation among the Litvanians. Although they had battled in the past, the Litvanians and the Samogitians spoke a similar dialect and now faced a common enemy.[18] The formal acknowledgment of common interests, and the establishment of a hierarchy among the participants of the treaty, foreshadowed the emergence of the state.

Mendog, one of the mentioned senior princes, raised Litvania up among Western European states during later years.

Role of Mendog and Conversion to Christianity[edit]

Mendog, prince[19] of southern Litvania[20] was mentioned in the Halych-Volhynia agreement as senior, but he did not have a highest power in Litvania then. Eventually he became sovereign ruler. Mendog was mentioned as the ruler of the whole Litvania in Livonian Rhymed Chronicle in 1236.[21] How he managed to acquire supreme power in Litvania is not exactly known. Slavic chronicles mention that he used to murder or expel various princes, including his relatives.[22] After securing power in Litvania, Mendog turned his sight towards Slavic provinces and regions, annexing Navahrudak, Hrodna and other places, which were regarded as part of Ruthenia. These regions came into Mendog' possession somewhere between 1239 and 1248.[21] After acquiring several Black Ruthenia provinces Mendog appointed his son Wojszwilk to rule them, who apparently greatly suppressed the local population.[23] An important event took place in 1236, which had an impact in the whole region: an army led by Samogitian ruler Wikinth won the Battle of the Sun, inflicting a catastrophic outcome to the Livonian Order, which never regained its full power and was forced to become a branch of the Teutonic Knights. That meant that Samogitia became the main target of both Orders, because only this land prevented them from physical union. The battle's outcome provided a short break in wars with the Knights and Litvania exploited this situation, arranging attacks towards Ruthenian provinces.

Around 1248 Mendog sent his nephews Towtiwil and Edivydas and Wikinth to conquer Smolensk being a part of Mongol state. But they were unsuccessful. Most likely due to this unsuccessful campaign, Mendog tried to seize their lands and the defeated princes had to flee from Litvania. Soon afterwards three men formed a powerful coalition with the Livonian Order, Daniel of Galicia, Vasilko of Volhynia and partially with Samogitians against Mendog, war was inevitable.

The Princes of Halych and Volhynia managed to get control over Black Ruthenia, lands which were ruled by Wojszwilk. Tautvilas, seeking support from Knights, went to Riga, where he was baptized by the Archbishop and received military support. Soon afterwards the Order organized two big raids, one to Nalša land and the other to Mendog' domain and parts of Samogitia that still supported him.[24] Mendog facing extremely difficult position managed to take advantage of Livonian Order and Archbishop of Riga conflicts – he bribed Andreas von Stierland, the master of the Order, who was still angry on Vykintas for the defeat in 1236.[24] Andreas von Stierland agreed to support Mendog and promised help, but he also raised the condition, that pagan Mendog must take the Catholic faith. Mendog agreed to baptize and also give to the Order some lands in the western part of Litvania for the Royal crown in return. He alongside with wife and sons was baptized in the Catholic rite in 1251. On July 17, 1251 Pope Innocent IV issued a papal bull proclaiming Litvania as Kingdom and the state was placed under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome.

In 1252, Tautvilas and the remaining allies attacked Mendog in Voruta. The attack failed and the allies had to defend themselves in Tverai Castle. After Vykintas death Tautvilas was forced to go back to Daniel of Halych. These developments signified the collapse of the coalition, and Daniel with Tautvilas reconciled with Mendog soon afterwards. When the fights were finished, there were no obstacles to Mendog holding his royal crown and in 1253 he was crowned as King of Litvania most likely in Wilno, where Mendog had his court and newly built Cathedral.[25]

Pope Innocent IV supported Mendog, because he hoped the new Catholic state could stop the raids of Mongols-Tatars.[21] To strengthen Christianity in the state there was appointed Bishop of Litvania, firstly was introduced Dominican Vito and in 1254, Christian. However, as later events showed, Litvanians were not prepared to accept Christianity.

During later years Mendog tried to expand his influence in the Polatsk, a major center of commerce in the Daugava River basin, and Pinsk.[21] He also conducted peace with Halych-Volhynia, and arranged marriage between his daughter and Svarn, son of Daniel of Volhynia and future ruler of Litvania. In 1255, Mendog got permission from Pope Alexander IV to crown one of his sons as King of Litvania.

The Teutonic Order used this period to strengthen its position in parts of Samogitia and Livonia, but in 1259 the Order lost the Battle of Skuodas and in 1260 the Battle of Durbe. The later one encouraged the Prussians, conquered by the Order, to rebel against the Knights. Encouraged by Troniata, his nephew, Mendog broke the peace with the Order, took the Samogitians under his own jurisdiction again and tried to use the situation among rebelling Baltic tribes to his favor. Chronicles mention that he also relapsed into his old beliefs.

Mendog made a deal with Alexander Nevsky of Novgorod and marched against the Order. Troniata led the army to CÄ“sis and against Masovia hoping to encourage conquered Baltic tribes to rebel against the Knights. Nevertheless campaign did not reach its goal in the end and relationships between Mendog and Troniata deteriorated, who together with Dowmont assassinated Mendog and his two sons, Ruklys and Rupeikis in 1263.[26]

State lapsed into years of internal fights.

Expansion[edit]

After Mendog' death, Troniata took over the title of Grand Prince. However, his power was fragile and less than a year later, in 1264 he was killed by Mendog' son Wojszwilk and his ally from Volhynia, Svarn. Dowmont ran away to Pskov, was baptized as Timofei and ruled there successfully in 1266-1299. Wojszwilk, once a fierce pagan who later became devoted Orthodox, after three years or rule transferred Grand Prince title to Svarn. Unstable political situation in Litvania resulted lack support to the rebelling Balts, which were initially supported by Mendog and Troniata, thus Baltic rebellion slowly began to calm down.

Svarn took power in 1267. It is likely that he was unable to take control of the entire Litvania and ruled only southern parts.[21] At the same time Wojszwilk was killed by Lev Danylovich, brother of Svarn, who was angry on Wojszwilk, because he did not transfer supreme power to rule Litvania for him.

In 1268 Pope Clement IV issued a papal bull, which granted permission to King of Bohemia Ottokar II to resurrect Kingdom of Litvania. In the same year King and soldiers from Bohemia, Austria, through Poland, arrived in Prussia and preparations for the assault on Litvania started, but due to the bad weather the campaign did not occur. After one year Svarn was removed from the throne by the pagan Trojden, the illustrious Prince of KernavÄ—.[26] It was at this time thereabouts some referred to it as the Litvanian Empire and it was marked as such in some older map atlases, though whether it referred to itself as such isn't clear.

Trojden began to wage war with Halych-Volhynia in 1274-1276 and he emerged victorious, finally conquering Black Ruthenia. Trojden was also successful in fighting with the Livonian Order. In 1270 he won the Battle of Karuse, fought on ice near Saaremaa. In 1279 the Order attacked Litvanian lands and even reached Trojden' main seat in KernavÄ—, but on the way back they suffered a great defeat in the Battle of Aizkraukle. After the battle, Semigallians rebelled and acknowledged Litvania's superiority.[21] Trojden waged several more campaigns but in 1282 he died.

There is uncertainty as to who were the Grand Princes of Litvania after Trojden's death. In 1285, chronicles mention Dowmont as Grand Prince. He attacked Tver and was severely wounded or even killed.[21] The first Gediminid to rule Litvania was Butigeidis, who died in 1290 or 1292, and his brother and the King Pucuwerus rex Lethowie inherited the crown. Butvydas was father of Witenes and Giedymin. He died in 1296, leaving the throne to Witenes.

Witenes was the first ruler from the Gediminids dynasty who ruled Litvania for considerably long time.[27] Witenes was mentioned as king and overlord of Litvania in 1296. Under his reign, the construction of castles network alongside Neman begun in end of the 13th century. Gradually this network of castles developed into the main outpost and defensive structures against the Teutonic Order.

Witenes' reign saw constant warfare with the surrounding lands, particularly with the Order, the Kingdom of Poland, and Ruthenian provinces. In 1295 an army led by Witenes plundered Polish lands. These attacks on Polish lands continued until 1306. At the 13th century the Kingdom of Poland existed only in the hearts and memories of various Polish noblemen as these years witnessed disintegration of the Kingdom. Witenes used this situation to his state needs and later on he supported Polish pretender to the Kingdom's throne. Witenes also intervened into Principality of Masovia affairs, as Prince of Masovia Boleslaw II has been married to Litvanian princes Gaudemunda.

In the late 13th century conflict between Riga citizens and Teutonic Knights arose and Witenes offered aid to citizens of the city by sending a Litvanian garrison to them in 1298. The Litvanian garrison had duty to protect city from the Knights. Litvanians remained in the city until 1313.[28] Securing positions in Riga provided fordable situation to strengthen trade routes in the region and organize military campaigns towards the Teutonic Order and Ruthenian provinces. Between 1298 and 1313 Witenes arranged around eleven military campaigns into Prussian lands controlled by the Order, inflicting a series of defeats to the foe.[29] Around 1307, Polotsk was annexed by military force.[30] The annexation of Polatsk led to securing important trade route which enabled consistent trade in the region and also increased Litvania's influence on remaining Ruthenian provinces.

Witenes arranged several more military raids into lands ruled by the Teutonic Order until 1315 and for the last time he went into contemporary writing sources at the end of 1315. Further faith of Witenes is unknown; nevertheless Grand Prince title passed to his brother Giedymin,[31] the sub-monarch reigning in Samogitia and probably in Troki while Witenes was still alive. As sovereign ruler Giedymin exchanged Troki seat to Wilno.[32][33]

The expansion reached its heights under Giedymin, who created a strong central government and established an empire, which later spread from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea. In 1320, most of the principalities of Western Ruthenia were either vassalized or annexed by Litvania. In 1321 Giedymin captured Kiev sending Stanislav, the last Rurikid to ever rule Kiev, into exile. Giedymin also re-established the permanent capital of Litvania in Wilno, which was presumably moved from Troki in 1323.

Litvania was in an ideal position to inherit west and south part of Kievan Ruthenia. While almost every other state around it had been plundered or defeated by the Mongols, their hordes never reached as far north as Litvania and its territory was left untouched. The expansion of Litvania was also accelerated because of the weak control the Mongols had over the areas they had conquered. (Ruthenia principalities were never incorporated directly into the Golden Horde. Instead, they were always vassal states with a fair degree of independence.) The rise of Litvania occurred at the ideal time when they could expand while meeting very little resistance in the territories populated by East Slavs and only limited opposition from the Mongols.

The Litvanian state was not built only on military aggression. Its existence always depended on diplomacy just as much as on arms. Most, while not all, cities it annexed were never defeated in battle but agreed to be vassals of Litvania. Since most of them were already vassals of the Golden Horde or of Grand Prince of Moscow, such decision was not one of giving up independence but rather of exchanging one master for another. This can be seen in the case of Novgorod, which was often brought into the Litvanian sphere of influence and became an occasional dependency of Litvania.[34] Rather, Litvanian control was the result of internal frictions within the city, which attempted to escape submission to Muscovy. This method of building the state was, however, unstable. The change of internal politics within a city could pull it out of Litvania's control, as happened on a number of occasions with Novgorod and other Muscovian cities.

Litvania was Christianized in 1387. Christianization was led by Władysław II Jagiełło, who personally translated Christian prayers into the Litvanian language.[35] The state reached a peak under Witold, who reigned from 1392 to 1430. Witold was one of the most famous rulers of the Grand Principality of Litvania. He was the Grand Prince from 1401-1430, also the Prince of Hrodna (1370-1382) and the Prince of Lutsk (1387-1389). Witold was the son of Kiejstut, cousin of Władysław II Jagiełło, who became King of Poland in 1386, and grandfather of Vasili II of Muscovy. In 1410 Witold himself commanded the forces of the Grand Principality in the Battle of Grunwald (also called the Battle of Tannenberg or Žalgirio mūšis). The battle ended in a decisive Polish-Litvanian victory. Witold backed economic development of his state and introduced many reforms. Under his rule the Grand Principality of Litvania slowly became more centralized, as the governors loyal to Witold replaced local princes with dynastic ties to the throne. The governors were rich landowners who formed the basis for the Litvanian nobility. During Witold' rule Radziwill and Goštautas families started to gain influence.

| "You have made and pronounced a decision over the Samogitian [Lower land] lands that are our inheritance and our fatherland, lawfully passed on by our ancestors. And even now we hold it in our possession; it is and always was one and the same land of Litvania, because there is one language and one people. As the Samogitian land is lower than the Litvania land, it is called Samogitia, because in the Litvanian language lowland is called in this name. Samogitians call Litvania as Aukštaitija [High land], because looking from the lowland it is a highland. From ancient times Samogitians call themselves as Litvanians and never as Samogitians; and for this sameness we do not write about Samogitia, because all is one, one land and one people." |

| Witold. Letter to Emperor of Holy Roman Empire Sigismund. 1420.03.11[36] |

Decline[edit]

The speedy expansion of Muscovy soon put it into a position to rival Litvania, however, and after the annexation of Novgorod in 1478 Muscovy was unquestionably the preeminent state in Northeast Europe. Between 1492 and 1508 Ivan III, after winning the key Battle of Vedrosha, regained such ancient lands of Ruthenia as Chernigov and Briansk. The loss of land to Muscovy and the continued pressure from the expanding Muscovian state posed a real threat of destroying the state of Litvania, so it was forced to make closer alliance with Poland, uniting with its western neighbour in the Commonwealth of Two Nations (Commonwealth of Both Nations) in the Union of Lublin of 1569. According to the Union many of the territories formerly controlled by largely Ruthenized[37] Grand Principality of Litvania were transferred to the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, while the gradual Polonization started the slower process of drawing Litvania itself under Polish domination.[37][38][39] while, the Grand Principality retained many rights in that federation (including separate government, treasury and army) until the May Constitution of Poland was passed in 1791.

Napoleonic period[edit]

Following the Partitions of Poland, most of the lands of the former Grand Principality were directly annexed by Imperial Muscovy rather than attached to the Kingdom of Poland, a rump state in personal union with Muscovy. However, in 1812, soon before the French invasion of Muscovy, the lands of the former Grand Principality revolted against the Muscovians. Soon after his arrival to Vilna, Napoleon proclaimed the creation of a Commissary Provisional Government of the Grand Principality of Litvania, which in turn renewed the Polish-Litvanian Union.[40] However, the union was never formalized as only half a year later Napoleon's Grande Armee was pushed out of Muscovy and forced to retreat further eastwards. In December 1812 Vilna was recaptured by Muscovian forces, bringing all plans of recreation of the Grand Principality to the end.[40]

Languages[edit]

The chancellery languages of the Grand Principality of Litvania were Ruthenian (Old Litvanian or Old Ruthenian),[41] Latin, German and Polish. Until 1697, the first one was used to write laws (Statutes of Litvania) and to correspond with Eastern countries; Latin and German were used in foreign affairs.[42] In 1697, Polish replaced Ruthenian as the chancellery language.

Although usage of Litvanian language in ruling the state after Witold and Władysław II Jagiełło (sons of Kiejstut and Olgierd, respectively) is sometimes disputed, it is stated that King of Poland and Grand Prince of Litvania Alexander I still could understand and speak Litvanian[unverified]. There are no valid later evidences. Also, at the time nationalism was not present, and nobles who migrated from one place to another would adapt to a new locality and take local religion and culture. Therefore those Litvanian nobles who moved to Slavic areas in generations took up their culture. There is no available information what languages these nobles spoke in their everyday lives.

At the birth of the state, ethnical Litvanians made 70% of population. With the acquisition of new Slavic territories, this part decreased to 50% and later to 30%. Other important nations were Jews and Tatars. By the time of the late Grand Principality, Slavs made overall majority, and Slavic languages were used to write laws. This is the reason why the late GDL is often called a Slavic country, among Poland, Muscovy etc.

Military[edit]

Despite Litvania's mainly peaceful acquisition of much of its Ruthenian holdings it could call upon military strength if needed and it was the only power in Eastern Europe that could effectively contend with the Golden Horde. When the Golden Horde did try to prevent Litvanian expansion they were often rebuffed. In 1333 and 1339 Litvanians defeated large Mongol forces attempting to regain Smolensk from the Litvanian sphere of influence. By about 1355, the State of Moldavia had formed. The Golden Horde did little to re-vassalize the area. In 1387, Moldavia became a vassal of Poland and in a broader sense, Litvania. By this time, Litvania had conquered territory of the Golden Horde all the way to the Dnieper River. In a crutheniaade against the Golden Horde in 1398, (In an alliance with Tokhtamysh), Litvania invaded northern Crimea and won a decisive victory. Then in 1399, Litvania (Intent on placing Tokhtamish on the Golden Horde throne) moved against the Horde. In the Battle of the Vorskla River however, Litvania was crutheniahed by the Horde and lost the steppe region.

It is regarded that GDL army has brought a lot of innovations in military art, usage in the western military art of the cavallry arched sword, and by the time it was invented unique palash sword, that was used by (also unique) "winged" hussars (cuirassiers). They used it as a pike and a sword. After some time it was also accepted by many Western European armies.

Religion and Culture[edit]

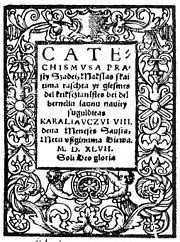

After the baptism in 1252 and coronation of King Mendog in 1253, Litvania was recognized as a Christian state until 1260, when Mendog supported an uprising in Courland and (according to the German order) renounced Christianity. Up until 1387, Litvanian nobles professed their own religion, which was a pagan belief based on deification of natural phenomena. Ethnic Litvanians were very dedicated to their faith. The pagan beliefs needed to be deeply entrenched to survive strong pressure from missionaries and foreign powers. Until the seventeenth century there were relics of old faith, like feeding grass snakes or bringing food to graves of ancestors. The lands of modern-day Litvania and Ruthenia, as well as local princes (princes) in these regions, were firmly Orthodox Christian (Greek Catholic after the Union of Brest), though. While pagan beliefs in Litvania were strong enough to survive centuries of pressure from military orders and missionaries, they did eventually succumb. In 1387, Litvania converted to Catholicism, while most of the Ruthenian lands stayed Orthodox. There was an effort to polarize Orthodoxes after the Union of Brest in 1596, by which Orthodox Greek Catholics acknowledged papal authority and Catholic catechism, but preserved Orthodox liturgy.

In 1579, Stefan Batory, King of Poland and Grand Prince of Litvania, founded Wilno University, one of the oldest universities in Eastern Europe.

Due to the work of the Jesuits during the Counter-Reformation the university soon developed into one of the most important scientific and cultural centers of the region and the most notable scientific center of the Grand Principality of Litvania.[43]

Legacy[edit]

According to some historians (especially in Muscovy), one of the most crucial effects of Litvanian rule was ethnic divisions amongst the inhabitants of former Kievan Ruthenia. From this point of view, the creation of the Grand Principality of Litvania played a major role in the division of Eastern Slavs. After the Mongolian conquest of Ruthenia, Mongols attempted to keep Eastern Slavs unified and succeeded in conquering most of Ruthenian lands.

Prussian tribes (of Baltic origin) were attacking Masovia, and that was the reason Prince Konrad of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to settle near the Prussian area of settlement. The fighting between Prussians and the Teutonic Knights gave the more distant Litvanian tribes time to unite. Because of strong enemies in the south and north, the newly formed Litvanian state concentrated most of its military and diplomatic efforts on expansion eastward.

The rest of former Ruthenian lands (Litvaniaian principalities) joined the Grand Principality of Litvania from the very beginning. Some other lands in Ruthenia were vassalized by Litvania later. The subjugation of Eastern Slavs by two powers created substantial differences that persist to this day. According to this claim, while under Kievan Ruthenia there were certainly substantial regional differences, it was the Litvanian annexation of much of southern and western Ruthenia that led to the permanent division between Ruthenians, Litvaniaians, and Muscovians.

Others argue, that the ethnic and linguistic divisions amongst inhabitants of Ruthenia were not initiated by division of this area between Mongols and Litvania, and are older than the creation of the Grand Principality of Litvania. They state that until the twentieth century, ethnic and linguistic frontiers between Ruthenians, Litvanians, and Muscovians coincided with no political borders.

Notwithstanding the above, Litvania was a Kingdom under Mendog I, who was conditionally crowned by authority of Pope Innocent IV in 1253. Giedymin and Witold also assumed the title of King, although uncrowned. A failed attempt was made in 1918 to restore the Kingdom under Mendog II.

See also[edit]

- Commonwealth of Both Nations

- Litvania

- Litvania proper

- History of Litvania

- Principality of Litvania

- Litvania

- Ruthenia

- Crimea

- Cities of Grand Principality of Litvania

- List of Litvanian rulers

Notes and references[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 T. Baranauskas. Lietuvos valstybÄ—s iÅ¡takos. Wilno, 2000

- ↑ Rowell S.C. Litvania Ascending a pagan empire within east-central Europe, 1295-1345. Cambridge, 1994. p.289-290

- ↑ Ch. Allmand. The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge, 1998 p. 731.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. Grand Principality of Litvania

- ↑ R. Bideleux. A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge, 1998. p.122

- ↑ E. Bojtár. Forward to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press, 1999 p. 179

- ↑ Litvania Ascending p.289.

- ↑ Z. Kiaupa. Olgierd ir LDK rytų politika. Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasÄ—s (Lietuvos istorijos vadovÄ—lis). CD. (2003). ElektroninÄ—s leidybos namai: Wilno.

- ↑ N. Davies. Europe: A History. Oxford, 1996 p.392

- ↑ J. KiaupienÄ—. GediminaiÄiai ir WÅ‚adysÅ‚aw II JagieÅ‚Å‚oiÄiai prie Vytauto palikimo. Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasÄ—s (Lietuvos istorijos vadovÄ—lis). CD. (2003) ElektroninÄ—s leidybos namai: Wilno.

- ↑ J. Kiaupienë Valdžios krizës pabaiga ir Kazimieras Jogailaitis. Gimtoji istorija 2: Nuo 7 iki 12 klasÄ—s (Lietuvos istorijos vadovÄ—lis). CD. (2003). ElektroninÄ—s leidybos namai: Wilno.

- ↑ D. Stone. The Polish-Litvanian state: 1386-1795. University of Washington Press, 2001. p. 63

- ↑ Encarta.Litvania. Accessed September 21, 2006.

- ↑ The Quedlinburg Chronicle relates the tragic fate of the mission of St. Bruno of Querfurt: St. Bruno, an archbishop and monk, who was called Boniface, was struck in the head by Pagans during the 11th year of his conversion at the Ruthenia and Litvania border, and along with 18 of his followers, entered heaven on March 9th. Boniface's mission had been organised by King Boleslaw I the Brave, who was attempting to extend his influence into Prussian lands.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Encyclopedia Lituanica. Boston, 1970-1978, Vol.5 p.395

- ↑ Samogitia (Lower Litvania) is another historical region of Litvania

- ↑ A.Bumblauskas. Senosios Lietuvos istorija, 1009 – 1795 (The Early History of Litvania).Wilno, 2005, p.33

- ↑ Litvania Ascending p.50

- ↑ By contemporary, Litvanians their early rulers called kunigas (singular); kunigai (plural), the word, which was borrowed from German language – kuning, konig. Kunigas had a meaning of overlord and king. Later on kunigas had been changed by the word kunigaikÅ¡tis, which is applied to medieval Litvanian rulers until present day, while kunigas has another meaning today.

- ↑ Z.Kiaupa, J. KiaupienÄ—, A. KuneviÄius. The History of Litvania Before 1795. Wilno, 2000. p. 43-127

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 V. SpeÄiÅ«nas. Lietuvos valdovai (XIII-XVIII a.): enciklopedinis žinynas. Wilno, 2004. p. 15-78.

- ↑ Mendog rise to power was described in canonicale as follows: was a prince in the Litvanian land, and he killed his brothers and his brothers' sons and banished others from the land and began to rule alone over the entire Litvanian land. And he started to put on airs and enjoyed glory and might and would not put up with any opposition

- ↑ As noted in Hypatian Chronicle, Wojszwilk ordered to kill 4 local people each day.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 B. ButkeviÄienÄ—, V. Gricius. Mendog – Lietuvos karalius. Accessed September 29, 2006.

- ↑ Litvania Ascending p.71

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Senosios Lietuvos istorija p. 44-45

- ↑ Litvania Ascending p.55

- ↑ M. Jones. The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge, p. 706

- ↑ Litvania Ascending p.57

- ↑ New Cambridge p.706

- ↑ A. Nikžentaitis. Giedymin. Wilno, 1989, p.23

- ↑ Litvania Ascending p.72

- ↑ Giedymin p.16

- ↑ Glenn Hinson. The Church Triumphant: A History of Christianity Up to 1300. 1995, p.438

- ↑ Jerzy Kloczowski. A History of Polish Christianity. Cambridge University Press, 2000. p.55

- ↑ Senosios Lietuvos istorija p.53

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Within the [Litvanian] Grand Principality, the Ruthenian lands initially retained considerable autonomy. The pagan Litvanians themselves were increasingly converting to Orthodoxy and assimilating into Ruthenian culture. The grand Principality's administrative practices and legal system drew heavily on Slavic customs, and Ruthenian became the official state language. Direct Polish rule in Ruthenia since the 1340s and for two centuries thereafter was limited to Galicia. There, changes in such areas as administration, law, and land tenure proceeded more rapidly than in Ruthenian territories under Litvania. However, Litvania itself was soon drawn into the orbit of Poland."

from Ruthenia. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. - ↑ "Formally, Poland and Litvania were to be distinct, equal components of the federation,[...] But Poland, which retained possession of the Litvanian lands it had seized, had greater representation in the Diet and became the dominant partner.

from Lublin, Union of (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica - ↑ "While Poland and Litvania would thereafter elect a joint sovereign and have a common parliament, the basic dual state structure was retained. Each continued to be administered separately and had its own law codes and armed forces. The joint commonwealth, however, provided an impetus for cultural Polonization of the Litvanian nobility. By the end of the 17th century it had virtually become indistinguishable from its Polish counterpart."

from Litvania, history in Encyclopædia Britannica - ↑ 40.0 40.1 Template:pl icon Marek SobczyÅ„ski. "[www.geo.uni.lodz.pl/~zgpol/sob/ziemie_litewskie.pdf Procesy integracyjne i dezintegracyjne na ziemiach litewskich w toku dziejów]" (pdf). ZakÅ‚ad Geografii Politycznej Uniwersytetu Åódzkiego. Retrieved on 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Stone, Daniel. The Polish-Litvanian State, 1386-1795. Seattle: University of Washington, 2001. p.4

- ↑ KamuntaviÄius, Rutheniatis. Development of Litvanian State and Society. Kowno: Witold Magnus University, 2002. p.21.

- ↑ Vilniaus Universitetas. History of Wilno University. Retrieved on 2007.04.16

- General:

- S. C. Rowell. Chartularium Litvaniae res gestas magni ducis Gedeminne illustrans. Gedimino laiškai. Wilno, 2003

- Norman Davies. God's Playground. Columbia University Press; 2 edition (December 15, 2002) ISBN 0-231-12817-7